Out of Chaos was a 1944 propaganda film featuring the works of acclaimed British artists, like Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Henry Moore, and Graham Sutherland, alongside those by amateur painters from the Firemen Artists and the Civil Defence Artists groups.1 Sharing a morale-boosting purpose with other war-time documentaries, this film stood out for delving into issues regarding art appreciation and interpretation that go beyond a mere propagandistic intent.

Out of Chaos marked the debut as director and writer of pioneering filmmaker Jill Craigie (1911-1999). A socialist and a feminist with a remarkable talent for directing, Craigie’s considerable body of work has only been rediscovered in the past two decades after years of oblivion.2 The documentary on war artists reflected her socialist vision of democratically bringing art to the people and was inspired by the ideals of William Morris and John Ruskin.3 Its title closely echoed Oscar Wilde’s pamphlet The Critic as Artist (1891): life is chaos and art’s purpose is to turn that rough subject matter into form – and beauty. The word “chaos” is indeed repeated as a refrain at the beginning of every dramatic scene that the artists in the film turn into a work of art.

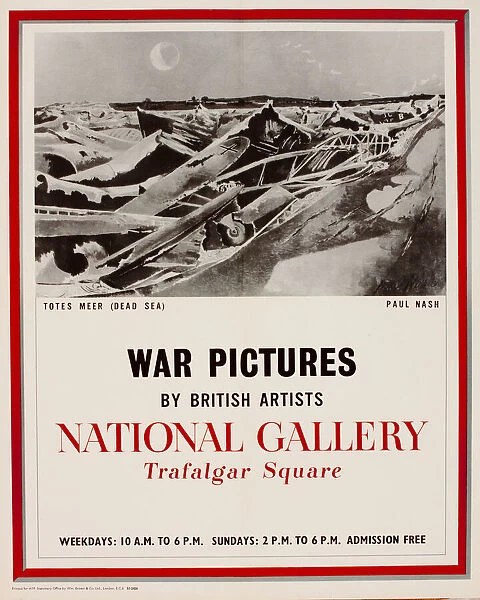

The democratisation of art was a priority of the wartime cultural policy promoted by the Ministry of Information (MoI) and its two leading figures Kenneth Clark (1903-1983) and John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). The ‘Art for the People’ scheme bringing travelling exhibitions and programmes of factual films about art was developed with the specific purpose of broadening the public’s participation and access. When Craigie took her project to Kenneth Clark, she immediately struck a chord with the young and influential Director of the National Gallery. Clark was then known as the “dictator of British art”: the man who was invited to every radio show about art, every exhibition, and committee.4 Clark also sat on the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA) and was the driving force behind the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC, 1939-45) created with the purpose of employing living artists to record the struggle and strife of the Battle of Britain.5 The paintings commissioned by the WAAC were displayed in a series of exhibition of War Pictures by British Artists around the country and abroad.6 The shows were a success and as a result approximately 6,000 works by leading British artists were distributed to museum in Britain and across the Commonwealth. The selection of war artists represented the “tradition of popular but ennobled figuration” and “classical heroism” championed by Clark.7 By supporting names like John Piper, Graham Sutherland, Paul Nash, Henry Moore, or Stanley Spencer, Clark favoured a moderate modernism that was neither too abstract nor too naturalistic.8 Clark’s marginalisation of abstract artists was severely criticised by other critics like Herbert Read; C.R.W. Nevinson’s attack against “Kenneth Napoleon Clark” was particularly vitriolic: “it would be better to be gassed by the enemy than breathe in a hothouse atmosphere of museum cranks and didactic favouritism.”9 Alongside professional artists, the WAAC also supported amateur painters such as Firemen Artists and Civil Defence Artists. Their work, too, was the target of criticism of Royal Academicians who saw them as incompetent painters.10 For Clark, Out of Chaos was an opportunity to defend the war artists initiative by capitalising on the public acclaim of the exhibitions and demonstrating that the money spent on contemporary artists was a worthy cause.

Despite Clark’s connections with the war artists, Craigie was left the task of convincing them to participate in her documentary. While John Piper refused, others were more keen to show their paintings.11 Clark’s endorsement did not equally translate into financial backing, leading to speculate that the MoI would not have sponsored a film by an inexperienced female director. Craigie, however, managed to persuade the movie tycoon J. Arthur Rank and the Italian producer Filippo Del Giudice, whose company Two Cities produced the documentary for a rather modest budget, £ 7,000. William MacQuitty, the producer who worked on Out of Chaos with Craigie, later recalled in his memoir that Del Giudice was taking a big risk “with an untried woman director […] and a subject that lacked mass appeal.”12

The film opens on the National Gallery bustling with visitors, even busier than in peace time, the voiceover comment underlines. What sort of people like to look at paintings for leisure? A cross-section is shown in answer to the narrator’s question: a soldier on leave, a couple, businessmen, and a bespectacled intellectual, the more typical museum goer. The voiceover presses on: The voice presses on: “Why in the height of war should there be this terrific interest in painting?” In 1939, artists stopped making art, paintings in houses were taken down, art dealers shut their shop, and the walls of public art galleries were stripped. The National Gallery was no exception as its masterpieces were transferred to hiding places in Welsh slate quarries. In their place, modern works of art were put on display in the first exhibition of war artists that opened in July 1940.

Clark then appears in his office, behind him a carved Madonna and Child, and an array of paintings ready to be packed convey the sense of emergency, but also to create an immediately recognisable setting for the connoisseur at work.13 Clark was no stranger to the camera, having appeared on camera for the first time in 1937 to illustrate the paintings of the Florentine School in the National Gallery. In 1939, he presented his first programme, Sight and Sound, a quiz show where poets had to recognise works of art, and artists quotes from poems. On the set of Out of Chaos, Clark was rather nervous nonetheless, so Craigie suggested that he sit on the edge of the desk and use his hands to emphasise the salient points.14 Her piece of advice certainly helped Clark become the confident TV performer that would later become a household name with the series Civilisation (BBC2, 1969). At the MoI, Clark was appointed head of the film division, according to him, because he knew a great deal about ‘pictures’.15 As a result , the British art historian starred in several documentaries, including the short propaganda film by Humphrey Jennings and Stewart McAllister, Listen to Britain (1942), where he had a cameo role as a listener at a Myra Hess piano concert sitting next to Queen Elizabeth.16 The very popular lunch-time concerts of chamber music at the National Gallery were part of Clark’s efforts to maintain the museum’s central cultural role during the war.17 Listen to Britain also showed the National Gallery rooms filled with visitors inspecting the works of war artists and flicking through the postcards reproducing old masters’ paintings. The postcards were another idea of Clark’s to popularise the masterpieces whose details were lavishly illustrated in the popular publications One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery (1938) and More Details from Pictures in the National Gallery (1941). Quite significantly, the museum postcards would later serve as a starting point for John Berger’s discussion on the mechanical reproduction of works of art in the famous documentary series Ways of Seeing (BBC2, 1972) – often considered as a leftist response to Clark’s Civilisation.

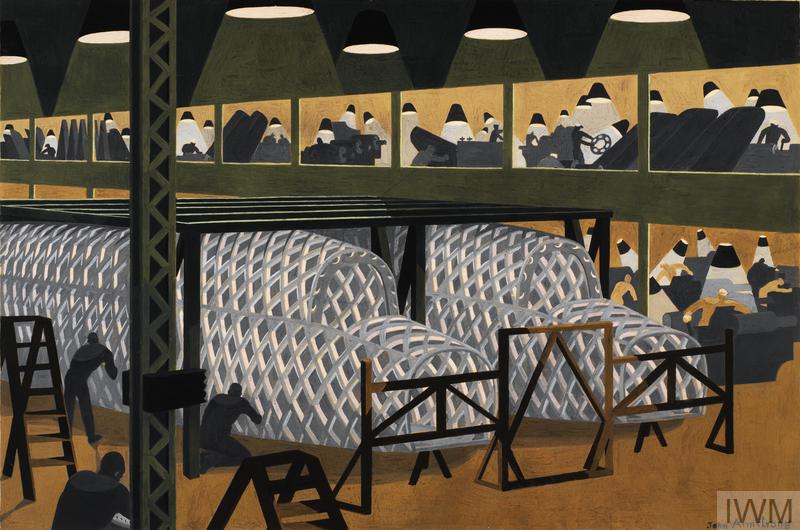

Going back to Out of Chaos, Clark proceeded to illustrate the WAAC commissions whereby artists were given subjects that resonated with their style. For example, aircraft manufacture suited the preference for sharp abstract forms of a painter like John R. Armstrong (1893-1973). Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1960), the only female war artist employed full time by the committee, was tasked with documenting the Women’s Land Army. Leslie Cole (1910-1976) was made the committee’s official artist in Malta.

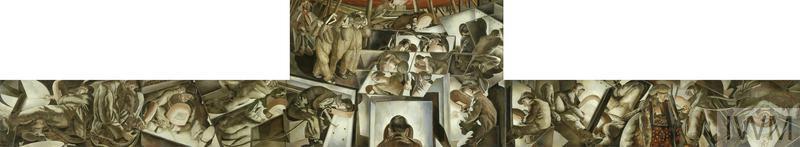

The first artist starring in the documentary was Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), whose interest in everyday life made him particularly apt to represent shipbuilding. Taking inspiration from a shipyard in Port Glasgow, Spencer painted a large-scale canvas Welders completed in his studio back in Cookham, Berkshire.18 Viewers could have easily understood the realistic depiction, but the words of critic Eric Newton are chosen to describe the painted scene compared to a mediaeval Last Judgement.

Paul Nash (1889-1946) represented the artist whose imagination shifted from imaginary, surrealist worlds to impactful images of the Battle of Britain. The film captured the creative process behind Totes Meer (1940-41, Tate Britain) as Nash made sketches of the wreckage in Cowley dump.19

The footage from Humphrey Jennings’ Fires Were Started (1943) reminds viewers of the all-too familiar scenes of London burning during the blitz, introducing the work of firemen artists. The painters and designers who volunteered in the Auxiliary Fire Service, unlike other artists, took active part in the actions that they depicted.20 Their work was shown in exhibitions organised by the War Artists Committee, which, as the voiceover underlines, attracted people who had never been to an art gallery before.

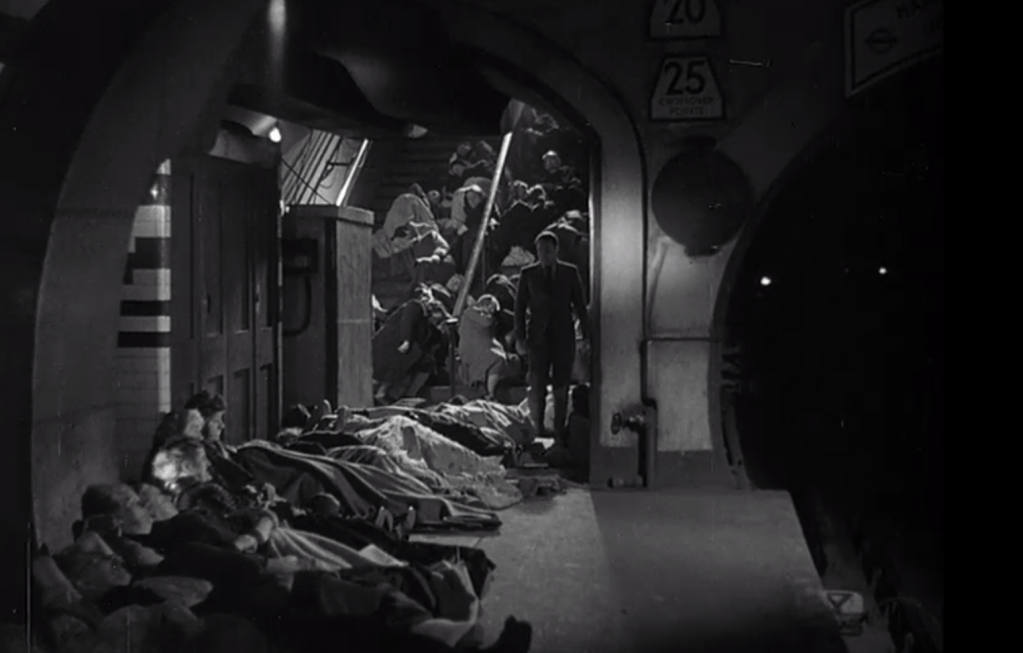

Henry Moore (1898-1986) had not yet achieved the fame that he would later enjoy, but he was undoubtedly the star of Out of Chaos. In what was only the first of many on screen appearances, Moore was the only artist in the documentary who explained his own work.21 The Yorkshire sculptor was filmed in the tube shelter in Holborn Underground Station in London as he walked among people sleeping, carefully observing, and making visual notes. Back in his studio in Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, viewers see the sketches and ideas turned into drawings. Acutely aware of the possibilities afforded by the camera, Moore skilfully illustrated his technique, drawing in white crayon that became visible after he washed the paper with dark watercolour. He asked that his sculptures would be filmed last to demonstrate the culmination of his working method, and carefully instructed the crew on how to light his pieces.22 Adding to Moore’s own words, art critic Eric Newton described the drawing Pink and Green Sleepers (1941, London, Tate) as it cross-faded into real-life sleepers.

The Blitz brought artists and common people closer together, as exemplified by the exhibitions of Civil Defence Artists organised by Denis Matthews in a gallery on Bond Street. In the select committee of art experts choosing among the many submissions, viewers would have later recognised the president of the Royal Academy, Sir Gerald Kelly (1879-1972), as the host of televised guided tours of art galleries in the late fifties. The inaugural speech delivered by the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, captured the spirit of these exhibitions and, by extension, the sentiment underpinning Out of Chaos: “I hope that this bond between the artist and the man in the street will outlast the war”.

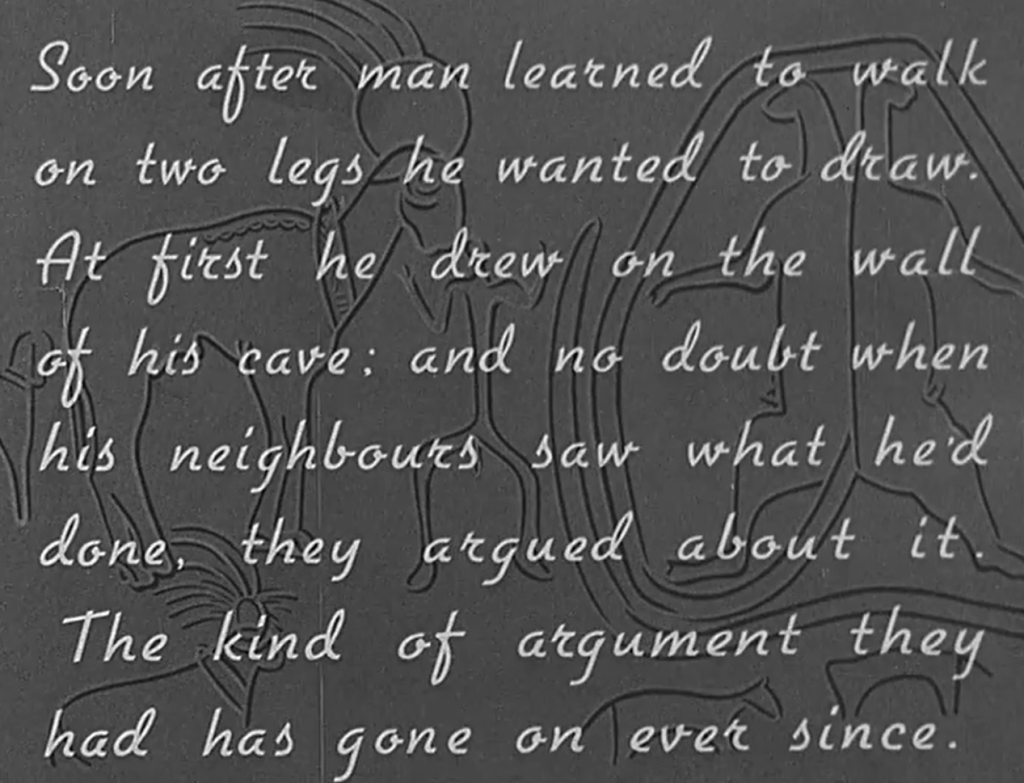

What place does art have in society? Ever since the primitive man traced the first cave drawings, contemporaries have been arguing about it. Reconnecting to this opening remark, the second part of the documentary attempted to answer this immemorial question focusing on interpretation. Returning to the National Gallery, viewers listen in to the comments made by ordinary visitors: “I can’t explain what I mean, but I know what I like”, “If this is painting, my small son’s a genius”, etc. The commentator hands it over to Eric Newton (1893-1965), a well-known name to the British public for his radio broadcasts, who embodies the enlightened art critic, the savant who understands and interprets art for the wider audience. At the bewilderment of bystanders, Newton praises Limestone Quarry by Graham Sutherland, only to be challenged: has the artist even seen a real quarry? Moreover, the painting needs explaining but beautiful pictures should be self-explanatory, another visitor interjects. The camera then follows Graham Sutherland (1903-1980) sketching in the limestone quarries in Hindlow, Derbyshire. Accurately studying the subject, Sutherland is “storing details” that he will later use for his composition completed in the studio. What appear as concessions to reality, such as the dark sky, are expressive choices to convey a feeling of the place. The cinematic medium is used to demonstrate this: changing colour fields show different options, and animated arrows highlight the composition.

Newton provocatively asks: should art be beautiful or express an idea? People tend to consider beautiful what they can understand. When someone points out that Constable or Turner need no explanation, Newton responds by quoting the criticisms they suffered when they were modern. Their likeness of nature is now appreciated because people have come to see nature through their eyes. In the face of the new, sooner or later, everyone develops a certain “hardening of the aesthetic arteries”. Even if people were able to read art, what use would it be to them? Newton’s reply delivers the final message of the film with words that could have been spoken by Clark himself: art is useful because it makes life more enjoyable.

Prodding the artist, deciding which artists to prod, and to what subjects they should turn their attention, was the purpose of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, as Eric Newton wrote in a catalogue of British war artists. The war artist would have to encompass three qualities, according to Newton:

First to furnish a description of the ‘look’ of the thing he is painting; second, to convince the spectator that the thing has been experienced as well as seen; and third, to present his experience as an integrated whole. […] Art is astonishing only when the three elements have been fused so completely that there is no possibility of separating them.23

In describing the quintessentially British qualities of these painters, the hint of patriotism is a sign of the time:

It is precisely the central quality of British painting that it can offer a personal interpretation of the visible world without abandoning the attempt to describe its detail with conscientious accuracy. […] The British artist rarely generalises. He stresses his subject’s characteristic qualities, yet he imposes his own vision on it. And if, as so often happens, his vision has a lyrical element, his picture will come to life as a work of art.24

Out of chaos blurs the boundaries between propaganda and art popularisation. While pursuing an emotional impact like other wartime films, Craigie’s documentary anticipated the educational mission that would become prevalent in post-war art documentaries. The use of multiple exposures, animations, and cross-fades also foreshadowed the cinematic effects largely employed in art films over the course of the following two decades.25 The film received critical acclaim, though it only circulated in art houses with no wider distribution, prompting a reviewer from the Sunday Express to write: “It tries something new and advances the cause of the cinema as an intelligent medium. It is so good. In fact it isn’t being shown anywhere!”26

Despite the limited distribution, Craigie’s short paved the way for many future British art documentaries. The artist at work in his studio, their struggle, tribulation, and creation, would become a very popular subject in the following two decades, Henry Moore being an absolute favourite. The war artists featured in Out of Chaos later starred in the films by John Read (1923-2011): Henry Moore (1951), Graham Sutherland (1953), John Piper (1953), Cookham Village (1956), War and Peace (1956) [about Stanley Spencer]. Other examples include Artists Must Live (Arts Council, 1953), Black on White (Arts Council, 1954), A Sculptor’s Landscape (BBC, 1959) on Henry Moore, up to the more experimental Monitor series (BBC, 1958-65). The art expert or connoisseur offering their opinion on works of art served as a precedent for the following pundit series. The debate on art and public engagement framed underpinning Out of Chaos was continued by Clark in the televised series Is Art Necessary? (ITV, 1958-59), exploring topics such as what is beautiful, what is good taste, figuration and abstraction, if art can be democratic, or if photography can be considered art.

The socialist humanism at the heart Out of Chaos was an enduring legacy that may have resonated with the more progressive and ideological documentary Ways of Seeing (BBC2, 1972). Berger’s commitment to debunking the myths perpetuated by orthodox art history stemmed from the same educational intent of bringing art to the people. Berger poignantly began the programme in a studio reconstruction of the National Gallery, although the museum is presented as an institution to be demystified. Berger, too, included interviews to children and feminists on their interpretation of works of art, but instead of representing the simplistic views of the uneducated, their unbiased, honest, and informed remarks flesh out the patriarchal and imperialistic gaze dominating Western art.

Even though there were a few female war artists, their work did not receive enough credit in Out of Chaos – the only exception being Evelyn Dunbar’s Women’s Land Army Dairy Training.27 A feminist approach to works of art would have been equally inconceivable at the time, even for an outspoken advocate for gender equality such as Craigie, whose views were certainly more vocal in the forward-thinking film To Be Woman (1951). Her political radicalism shaped her prolific filmography: from post-war reconstruction in Britain [The Way We Live (1946)]; Children of the Ruins (1948)], to nationalisation and workers’ rights [Blue Scar (1949)], to public housing [Who Are the Vandals? (1967)].

- The documentary can be streamed on the BFI website for UK viewers only. ↩︎

- On Jill Craigie see C.E. Rollyson, To Be a Woman. The Life of Jill Craigie (London: Aurum, 2005). Cf. also https://www.jillcraigiefilmpioneer.org/ and the documentary Independent Miss Craigie directed by Lizzie Thynne (British Film Institute, 2020). ↩︎

- Craigie explained “With mass production, industrial design and town planning, the artist is becoming increasingly important and useful to society. He has been neglected too long, and we can’t live full lives if we continue to ignore him. If we question the look of a painting, we will also question the look of other things, out houses and our towns.” (quoted in Rollyson, pp. 40-41). ↩︎

- Clark, indeed, remembered the thirties as “the Great Clark Boom”, K. Clark, Another Part of the Wood: A Self-Portrait (London: John Murray, 1974), p. 211. ↩︎

- B. Foss, War Paint: Art, War, State and Identity in Britain, 1939-45 (London-New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007); M. Bohm-Duchen, Art and the Second World War (Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013), pp. 33-55; D.A. Mellor, ‘Second World War’, in C. Stephens, J.-P. Stonard (eds.), Kenneth Clark. Looking for Civilisation (London: Tate, 2014), pp. 101-113; S. Llewellyn, P. Liss, WWII. War Pictures by British Artists (London: Zenith Media, 2016). ↩︎

- The catalogues were titled War Pictures by British Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1942). The opening lines read: “What did it look like? They will ask in 1981, and no amount of description or demonstration will answer them. […] Only the artist with his heightened powers of perception can recognise which elements in a scene can be pickled for posterity in the magical essence of style.” ↩︎

- Mellor 2014, p. 101. ↩︎

- Bohm 2013, p. 35. ↩︎

- C.R.W. Nevinson, ‘The artist in peace and war: his works vitalised by experience’, in Daily Telegraph (16 March 1940), quoted in Foss 2007, p. 175. ↩︎

- M. Secrest, Kenneth Clark: A Biography (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1984), p. 151. ↩︎

- Craigie had met many artists through her friend Malcolm MacDonald, see Rollyson 2005, pp. 38-39. ↩︎

- W. MacQuitty, A Life to Remember (London: Quartet Books, 1991), p. 289. ↩︎

- Secrest 1984, p. 165: “His aplomb, standing beside a magnificent desk and a statue of a Madonna and Child, was remarkable. In a few bold clear strokes he sketched in the outlines. The profile was more youthful, the voice pitched a trifle higher, but it was otherwise the Kenneth Clark millions of viewers would come to know, exquisitely dressed, and with that way of squaring his shoulders slightly before plunging into an assertion, and running his tongue rapidly across his teeth, oddly self-revelatory mannerisms which are, on camera, the essence of successful self-projection.” ↩︎

- MacQuitty 1991, p. 293. ↩︎

- K. Clark, The Other Half: A Self-Portrait (London: John Murray, 1977), pp. 9-10: “It was an inexplicable choice, and was commonly attributed to the fact that in those days films were spoken of as ‘pictures’, and I was believed to be an authority on pictures. I had no qualifications for the job, knew absolutely nothing about the structure of the film world; and was not aware of the difference between producers, distributors and exhibitors.” Clark found the government interference too stifling and eventually resigned from the MoI. ↩︎

- An excerpt of that film was featured in the first episode of Civilisation (BBC2, 1969). ↩︎

- Along with the war artists, he took old masters’ pieces out of storage and displayed them as painting of the month. ↩︎

- MacQuitty 1991, p. 291: “The giant cranes, cradles, slipways, gantrys, girders, and plates with their riveters and welders provided him with magnificent material.” ↩︎

- MacQuitty 1991, p. 289: “The relics of death and disaster lay in orderly rows of twisted metal as terrible mementoes of airmen’s desperate effort to survive. It was all too easy to visualise those last searing moments. Engines had smashed through air-frames already riddled with bullets and grotesquely melted seats nestled in the wreckage so that you half expected to see human fragments amid the horror.” ↩︎

- Cf. A. Kelly, Firemen Artists: 1940-45(London: Halstar, 2013). ↩︎

- Cf. J. Wyver, ‘Myriad Mediations: Henry Moore and His Works on Screen 1937-83’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/john-wyver-myriad-mediations-henry-moore-and-his-works-on-screen-1937-83-r1151304, accessed 19 October 2023 ↩︎

- As Craigie recalled, “not merely by suggesting where a shadow should fall and whether the correct depth of shade had been achieved, but by using all the right technical terms”, quoted in Rollyson 2005, p. 48. ↩︎

- E. Newton, War Through Artists’ Eyes (London: John Murray, 1945), pp. 7-8. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 10. ↩︎

- See, especially, the documentaries by Belgian filmmakers Henri Storck and Paul Haesaerts. ↩︎

- E. Betts, in Sunday Express (10 December 1944), quoted in MacQuitty 1991, p. 293. ↩︎

- Cf. K. Palmer, Women War Artists (London: Tate, 2011). ↩︎

Leave a comment