Joseph M.W. Turner’s dramatic and atmospheric landscapes are synonymous with what Nikolaus Pevsner liked to call the ‘Englishness of English art’. The champion and maker of his critical fortune, John Ruskin, believed if the painter’s immortality were to be reduced to a single work, the Slave Ship would have to be it. In Modern Painters, Ruskin wrote that his choice was motivated by the painting’s daring conception, perfect composition and accurate drawing; the subject was described as a sublime impression of “the power, majesty, and deathfulness of the open, deep, illimitable Sea”.1 The tragic irony that a quintessentially English artist was represented by a painting depicting a slave ship is not lost. The fact that Ruskin did not mention a word about the horrific event depicted, that is, the appalling decision to throw the ship’s human cargo overboard to claim insurance money, is a glaring example of how the dominant artistic narrative whitewashed the legacies of British slavery – and museums were largely complicit in legitimising white supremacy.

Museums have been instrumental in shaping national identity and citizenship based on an idealised notion of civilisation – a slippery word, to my mind, that can quickly turn into a supremacist mission to impose one’s worldview. As the temples erected to civilisation, museums play and have played an undeniable role in nation-building and empire-building through their displays aimed at creating a sense of self in relation to one’s country and the world. Canons are both reflected and established in the careful selection of what is displayed deciding what is worthy of being remembered or erased from our history and collective memory. The encyclopaedic scope of so-called ‘world museums’ is but another facet of western imperialistic gaze and oftentimes a testament to barbaric depredation – the very opposite of civilisation. As Andreas Huyssen pointed out, however, there is always “a surplus of meaning that exceeds set ideological boundaries, opening spaces for reflection and counter-hegemonic memory”.2

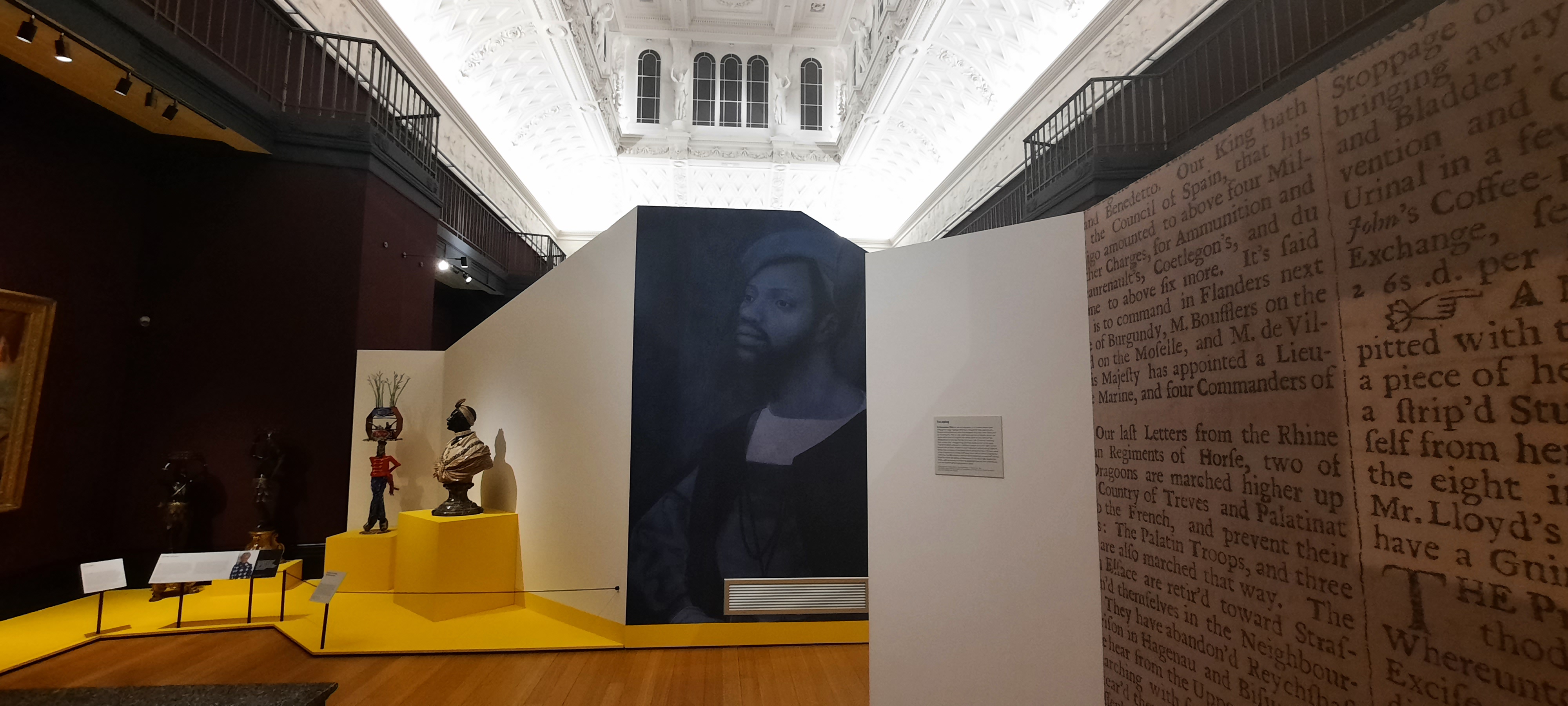

The thought-provoking exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, Black Atlantic Power, People, Resistance (8 September 2023 – 7 January 2024), is one of those moments in which the museum becomes a powerful stage for a counter-hegemonic storytelling. The first instalment of larger project, Black Atlantic seeks to investigate the historical and persistent marginalisation and erasure of the culture, artistic practices and belief systems shared by the people of the African diaspora. Calling attention to the museum’s direct links with the slave trade, this exhibition delves into “the living legacies of racism that have become baked into our systems, structures, practices and approaches” and shines a light on the wealth generated by enslavement that allowed the University of Cambridge to gather object and works of art from across the globe.3 Early modern and contemporary pieces in a wide range of media illustrate the visual strategies to demean Black identity and reinforce “Britain’s position as the leading Atlantic slave-trading power of eighteenth-century Europe.”4

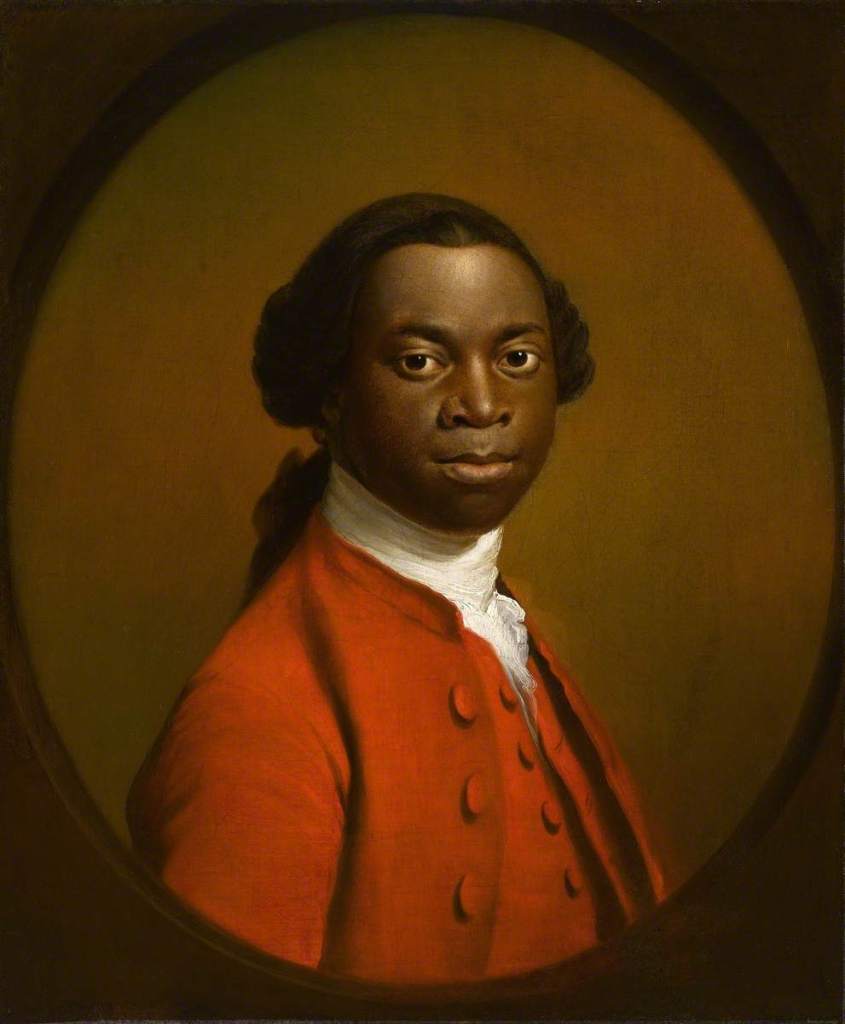

The central question that visitors are faced with is ‘who gets remembered and why?’. The answer may be inferred in the first two portraits on display where erasure is juxtaposed to canonised history. The Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit (1740-80, oil on canvas, Exeter, Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery) depicting an unrecorded Black man originally believed to be Olaudah Equaiano, by an equally anonymous artist, and the portrait of the future founder of the museum, Richard Fitzwilliam (1745-1816), painted by the famed Joseph Wright of Derby in 1764 (oil on canvas, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum). While very little information is known about the former, the latter boasts a well-documented pedigree: signed by the very prominent 18th-century painter, it was the first object of the Founding Bequest that entered the museum collection in 1819. A disclaimer warns the visitor of the terminology used in the panels: the classic art historical term “unknown” challenging the attributionist skills of the connoisseur is replaced by “unrecorded” signalling that history is the result of choices as well as omissions.

The expression ‘Black Atlantic’ was first coined by Robert Farris Thomson in 1983 for the visual and philosophical streams of creativity and imagination uniting Black people in the western hemisphere.5 Building on Thomson’s idea, Peter Gilroy defined the Black Atlantic as a rhizomorphic, transcultural formation existing between Europe, America, Africa, and the Caribbean inextricably linked to racial terror and slavery. Gilroy argued that the ideological tenets of western civilisations developed in the age of the Enlightenment, rationality, freedom, subjectivity and power, must be critically reconsidered in the light of the undeniable co-existence of enslavement, oppression and brutality.6 This dark and uncomfortable chasm between great scientific and humanitarian progress and inhumane exploitation highlighted in Gilroy’s work is the cornerstone of the Cambridge exhibition.

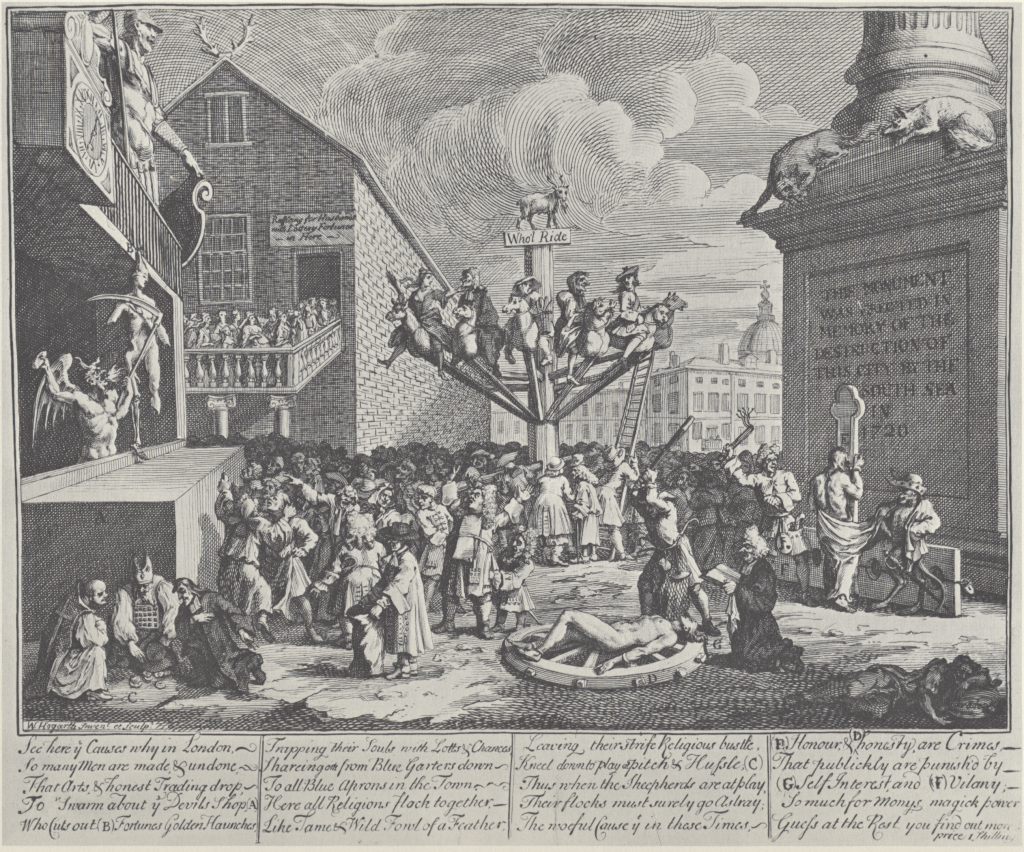

Looking into its own history, the Fitzwilliam Museum originated from a sizeable donation of artworks, books and money bequeathed to the University of Cambridge in 1816 by Richard 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam. A considerable share of his wealth came from Anglo-Dutch slave trading as his grandfather, Matthew Decker (1679-1749) had made profitable investments in the Royal African Company and was the founding director of the South Sea Company and subsequently Director of the East India Company.7 When the Crown subscribed the Asiento contract in 1713, the SSC secured a monopoly over the transatlantic slave trade and even though Decker resigned before the slaving voyages began, he greatly profited from the sale of the company stocks.8 As Jack Subryan Richards’ research shows, “the new annuities of 1733, which Fitzwilliam subsequently owned, restructured the Company’s existing capital when it was still engaged in slave-trading”.9 Matthew Decker was a typical product of the Anglo-Dutch connection that shaped the dominance of Atlantic slaveholding in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This close, and at times strained, entente that culminated in the accession of William of Orange to the British throne fostered the “burgher masculinity and cultures of consumption” that are evoked in the Dutch works of Gerrit Dou (The Schoolmaster), Rembrandt’s studio, Adriaen van Ostade, and Abraham Storck.10 The great fortunes to be gained from the slave trade led to unscrupulous financial schemes that resulted in the South Sea Bubble of 1720 which was emblematically lampooned in Hogarth‘s print The South Sea Scheme.

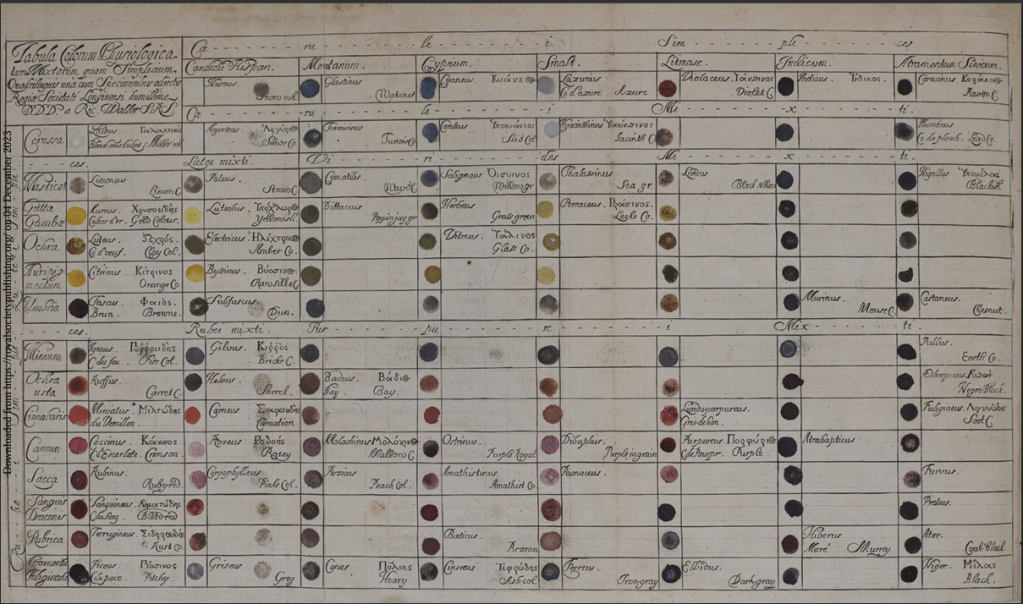

The astronomical instruments juxtaposed to a shotgun on the frontispiece of The History of the Royal Society of London, for the Improving of Natural Knowledge (London 1667) sanction the connection between the Royal Society and the twin-sister Royal African Company under the tutelage of Charles II. Colonialism and scientific knowledge go hand in hand in Richard Waller’s Table of Colours (1686-7) in which colours are accurately classified with the purpose of providing a pseudo-scientific explanation for racial discrimination. Based on hierarchy of skin tones such as ‘White’, ‘House Negro’ and ‘Field Negro’, Waller’s colourism is addressed in Keith Piper’s The Coloureds’ Codex (2023): a box of 15 pigments arranged according to arbitrary categories. Technological advances in navigation instruments, on the other hand, enabled colonial expansion and propelled the slave trade in the Middle Passage (i.e., the transatlantic crossing). The specimens collected in the colonies also furthered botanical and natural studies, like the first pineapple that Decker cultivated in his garden in Richmond proudly depicted in the painting commissioned to Theodorus Netscher (1720, oil on canvas, Cambridge, The Fitzwilliam Museum).

Black identity and the representation of Blackness in European art constitutes a focal point of the exhibition. In antiquity, slavery did not have the same racial connotations, enslavement often being the punishment for vanquished nations, as can be seen in the Relief of soldiers leading enslaved chained men with a wild animal fight below (200 CE, marble, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum). Before the Atlantic trade, Black people were rarely portrayed by western artists and when they were, they were normally represented as individuals. The exquisite Portrait of an African Man by Jan Jansz Mostaert (c. 1525-30, oil on panel, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) possibly represents Christophe le More, an archer at the Habsburg court of Emperor Charles V, or a member of the circle of Margaret of Austria. His high social status can be inferred from the expensive leather gloves, a richly ornate sword, and the insignia of the Lady of Halle on his hat. It is believed to be the earliest portrait of a Black person in European painting – previous examples such as Dürer’s Head of an African (1508) being only drawings. Wenceslaus Hollar’s etched portraits of African people (Six Portrait Heads, 1635-45) testify to the existence of Black communities in European cities in the 17th century.

The nativity was a Christian subject that provided artists with the opportunity for a less individualised and more conventional depiction of a Black African as the youngest Magus, King Balthasar, as can be seen in the Adoration of the Kings (1555-60, oil on panel, Cambridge, The Fitzwilliam Museum) by Taddeo Zuccari. As the slave trade developed, Black people would be featured in western art only as servants, objects or pieces of furniture. The nuances in pigmentation, too, were reduced as careful observation was replaced by racial stereotyping and a dehumanised portrayal that underscored European supremacy. In the Bust of an Enslaved Man by John Nost the Elder’s (c. 1700, coloured marbles, The Royal Collection), the dog’s collar around the subject’s neck recalls those that slaves were made to wear to mark their master’s ownership – as mentioned in the advertisements published in English newspapers when a slave went missing. Removed from the gruesome and appalling reality of slavery, European paintings offered a sanitised view of efficient work conditions on the plantations. Dirk Valkenburg’s painting of a party on a sugar plantation in Suriname (1706-08, oil on canvas, Copenhagen, National Gallery of Denmark) goes beyond ethnographic interest in so far as the detailed rendering of musculature is aimed at emphasising the slaves’ worth as commodities. Upon being commissioned a visual representation of colonial settlements in Brazil, Frans Post (1612-1680) painted scenes dominated by orderly industriousness, the brutality of enslaved manual labour dutifully omitted.

Contemporary artists have been working to recentre and re-write the narrative underlying western artistic canon. Hindsight is a luxury we cannot afford as part of the title of Alberta Whittle’s etchings reads. By recontextualising the brutalising imagery of natives in the illustrations of Columbus’s expeditions by Theodor De Bry (1528-1598), Whittle shines a light on the accepted visualisation of European colonising pursuits.

Barbara Walker’s reinterpretation of western masterpieces draws attention to the marginalisation of Black people in European art. In her drawings, blind embossing and tracing paper are powerful tools to redress the balance: once banished to the margins, Black figures are drawn in great detail while the remaining composition is muted or covered.11 In the series Vanishing Point and Marking the Moment, erasure becomes a “metaphor for how the Black community is overlooked, ignored, and even dehumanised by society” and a symbol of resilience against a canon based on race, class and power inequities.12

The Portrait of a Man in Military Costume (1650, oil on panel, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum) from Rembrandt’s studio painted on South American capomo and marmelero woods is an example of early colonial exports. From the 17th and 18th century, new commodities, pastimes, luxury goods on an unprecedented scale arrived in Europe as a product of imperialism. The connection to slavery and exploitation was often removed or normalised in the objects made to consume or store tea, coffee, sugar, chocolate, rum, and tobacco. Indigo, mahogany, ivory, silver and turtle shell were the other part of Black Atlantic material legacy. Jacqueline Bishop’s work History at the Dinner Table (2021) focuses on this problematic history by indigenising the iconography of China plate sets synonymous with British colonialism. The typical floral decorations are superimposed with the images of enslaved women being flogged, punished, and brutalised to draw attention to the harsh reality behind the fashionable idealised exoticism popular with European elites.13

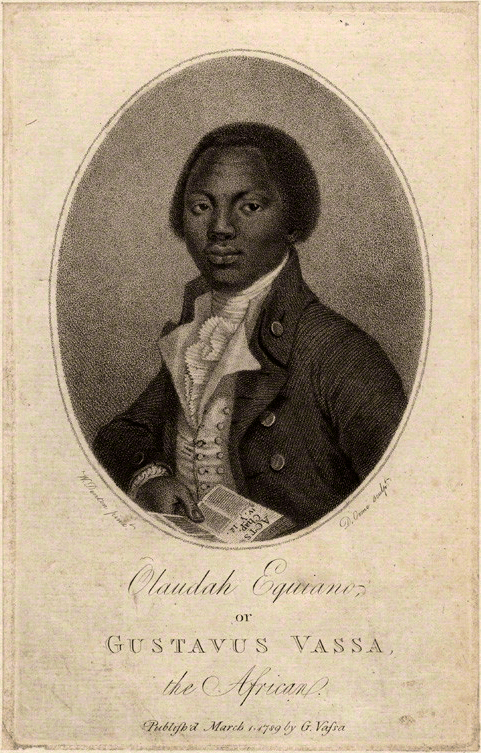

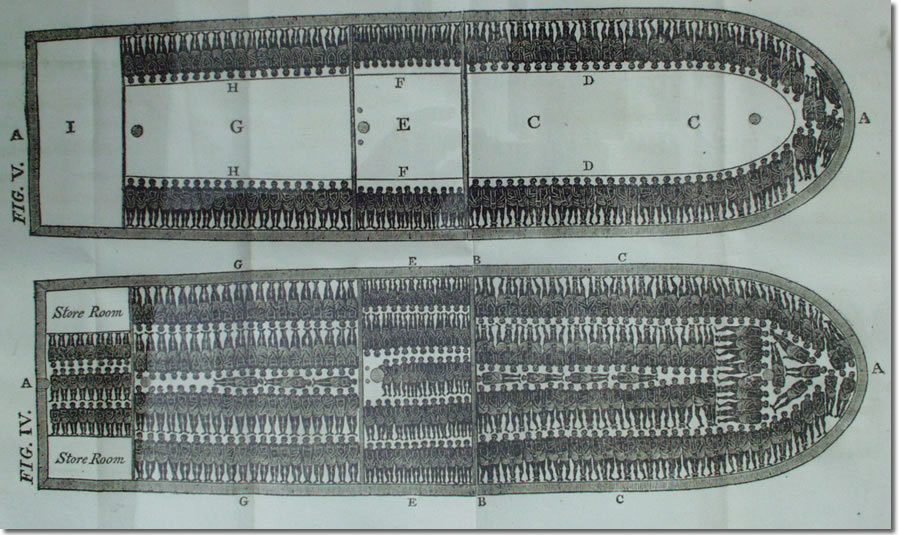

Black Atlantic traces a journey into selfhood and self-awareness that can be symbolically framed by the opening and closing works. The portrait of an unrecorded Black man formerly identified with Olaudah Equiano by an equally unrecorded painter epitomises the obfuscation of Black identity exerted by British dominant culture. In contrast, Alexis Peskine’s self-portrait Ifá (2020) stands for a Black artist taking control of his narrative, speaking a truth that was silenced for too long. Between these two polarities, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (London 1789) is an autobiographical first-hand account of the atrocities endured by enslaved people in the crossing of the Middle Passage.14 Freed in 1766, Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745-1797) settled in Cambridge in the 1780s and actively campaigned for the abolition of slavery joining forces with Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) whose 1808 book, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-trade by the British Parliament vividly illustrated the inhumane conditions aboard slave ships. The diagram outlining the stowage plan of the English slaver The Brooks is poignantly mounted with the American catchphrase ‘Go West Young Man’ from an 1865 campaign aimed at encouraging white males to settle westward in the namesake photomontage by Keith Piper (1987). Through the autobiographical lens of a conversation between father and son, Piper addresses Black British identity against the backdrop of the stereotypes of structural racism.

A selection of objects from Ghana, Suriname and the Caribbean offer a glimpse of the silenced or different (hi)stories before Atlantic enslavement. A testament to the richness and significance of Indigenous material and artistic culture, the presence of these objects in western collections may in some cases reveal the ties of their collectors to slavery. Though perhaps beyond the scope of the exhibition, provenance search often traces the history of Indigenous works as spoils of colonialism unlawfully acquired opening the debate on their restitution. Only a stone’s throw from the Fitz, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology holds 116 artefacts from the British sacking of Benin City in 1897 that are but one part of a hurtful legacy that the museum is committed to address and repair.15

An overthrown bell at the end of the exhibition serves as poignant reminder of the long-overlooked links between seats of learning and enslavement. Donated to St Catherine College in 1960, the De Catharina Bell cast in 1772 once marked the start and end of the relentless workday in the Dutch sugar plantation in Demerara. When its direct connections to slavery were fully understood, the bell was removed from its original site in 2019 and negotiations are underway for its restitution to Guyana. Reparative justice is a commitment that the Fitzwilliam pledges to uphold, researching and exposing the extent to which the museum still benefits in terms of finances and collections. Alexis Peskine’s Ifá (2020) made of nails speaks of physical and moral violence, displacement, plundering, and looting. The artist’s voice of resistance – “I am here!” becoming a powerful refrain – calls into question the re-investment of profits derived from the slave trade, “funding royal institutions, endowing universities, founding schools, setting up newspapers and building museums like this one”.

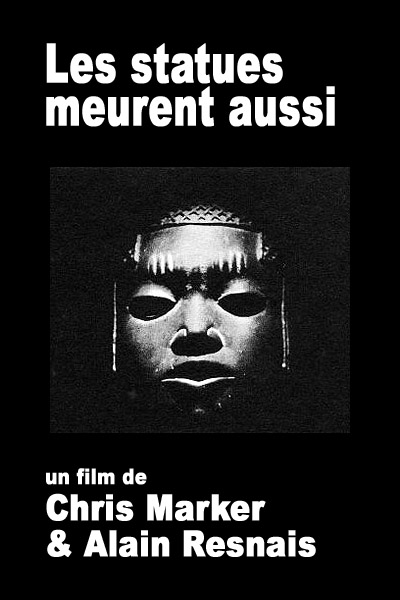

Outside the exhibition rooms, I became acutely aware of the whiteness of the marbles and the painted figures in the rest of the museum. A particularly fitting parallel were the scenes from Alain Resnais’s Les statues meurent aussi (‘Statues Also Die’, 1953), a groundbreaking documentary sponsored by the French journal and anti-imperialist movement Présence Africaine.16 In the opening lines, Resnais poignantly stated that “when men die, they become history, when statues die, they become art”, and in the museum, the purpose of (Indigenous) art becomes the visual pleasure of the European gaze. The same mortal predicament befalls all artistic civilisations that become part of the history of art. But in Resnais’s documentary, the works of African art in the British Museum, the Musée de l’Homme in Paris and the Musée du Congo Belge (now Royal Museum for Central Africa) in Tervuren bear testimony to a darker form of brutality, a “botany of death that we call culture”. This botany of death stemmed from what Achille Mbembe would later define necropolitics: the power to dictate who may live and who must die.17

The historic works and contemporary pieces on display in Cambridge attempt to question the museum’s role both past and present, its use as “a weapon, a method and a device for the ideology of white supremacy” and its ethical duty to acknowledge Black histories and identities.18 How the profits from the accursed slave trade permeated and still permeate many facets of British economic but also cultural life is a fact that can no longer be ignored. The Slavery Abolition Act Loan, the monetary compensation that the British government paid to slave owners, was extinguished as late as 2015.19 Museums such as the Fitzwilliam inevitably still benefit from the interests deriving from annuities paid to its donors and exhibitions like Black Atlantic lead the way of a long overdue critical reconsideration. Black Atlantic makes us aware of the racist bias underpinning western artistic canon materialised in collecting and display practices past and present. The burning question is: once these works return to their original gallery rooms, can – or indeed should – the cat be put back in the bag?

- J. Ruskin, Modern Painters. Vol. I (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1848), p. 378. ↩︎

- A. Huyssen, Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (New York – London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 15-16. ↩︎

- L. Syson, ‘Foreword’, in V. Avery, J. Subrayan Richards, Black Atlantic. Power, People Resistance (Cambridge: The University of Cambridge, 2023), p. 8. ↩︎

- Avery, Subrayan Richards, Black Atlantic, cit., p. 63. ↩︎

- R. Farris Thomson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983). ↩︎

- P. Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (London: Verso, 1993; cons. ed. 2022); The subtitle of this article is taken from a chapter in Gilroy’s book. ↩︎

- Sir Matthew Decker, 1st Baronet of Richmond Green was governor of the SSC between 1711 and 1712, and director of the East India Company from 1713 to 1743. ↩︎

- A full record of British slave voyages between 1780 and 1807 can be found on the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. ↩︎

- Avery, Subrayan Richards, Black Atlantic, cit., p. 28. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 30. ↩︎

- The works featured in the exhibition are the Adoration of the Kings by Paolo Veronese (London, National Gallery), the Family Group with a Black Man by Willem Conelisz Duyster (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), the Portrait of George Keith attributed to Placido Costanzi (London, National Portrait Gallery) and Portrait of Laura dei Dianti by Titian (Kreuzlingen, H. Kisters Collection). ↩︎

- Avery, Subrayan Richards, Black Atlantic, cit., p. 119. ↩︎

- See the film The Market Woman’s Story: Contemporary Ceramics by Jacqueline Bishop (2022). ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPkIouAElGA&t=508s ↩︎

- The object looted by the British punitive expedition will be returned to Nigeria, see https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/beninreturn. ↩︎

- Established in 1947, Présence Africaine rallied up Africanists and Africans with Blacks from the western hemisphere united under the banner of anti-imperialism; in 1959, this movement organised the Congress of Negro Writers and Artists in Rome to discuss “Negro culture” in terms of Black Atlantic heritage or the unity and diversity of Black cultures. ↩︎

- A. Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩︎

- D. Hicks, The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (London: Pluto Press, 2020), p. 15. ↩︎

- The records of the slave-owning families that applied for the compensation scheme can be consulted online on the database put together by the Centre for the Studies of the Legacies of British Slavery (UCL, London) https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/details/. Cf. also David Olusoga’s BBC documentary Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners ↩︎

Leave a comment