From Nikolaus Pevsner to Amartey Golding

albumen carte-de-visite, 1863, London, National Portrait Gallery; © National Portrait Gallery, London

Amartey Golding’s short film Britannia (2023) was recently on display at the Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.1 Having previously focused on his Black legacy (Chainmail, 2016-18; Is It Just Me, Or Is It You?, 2018; Bring Me to Heal, 2021), in this film the British-Ghanian visual artist delved into the “visceral history” of Englishness (or rather, Britishness) as part of his own cultural legacy.2 By addressing his white ancestry, Golding’s intent is to explore how the traumas of British history manifest themselves in the collective psyche. In Britannia as well as in other films, the artist draws on the embodied knowledge of communities through a process of self-reflection and self-implication that derives from his Rastafarian belief system.

Like Agnes Elsworthy, Britannia is represented by a middle-aged woman except that she is naked. Though initially she was supposed to be a man, Britannia is the first female and the first white character to be featured in Golding’s works and bears a close association with the artist’s mother. The woman wakes up in a quintessentially English countryside scene, in a moor by a lake and a forest is nearby. The sky looks ominous with a billowing cloud dominating the screen as the camera pans out. As she turns her attention to the sky above her, she notices a flock of tumbler pigeons soaring, spinning, and doing backflips. Making sense of her surroundings, she could be the first or the last woman on earth, she is not completely one with nature, blissfully running at first, then overcome by despair. Alongside her, two hounds galloping embody a sense of speed and freedom that quickly takes on a foreboding meaning as Britannia desperately tries to outrun them.

The film’s musical accompaniment is Antonin Dvořák’s New World Symphony (1893), which many Brits would recognise as the soundtrack to 1973 Hovis Bread advertisement – perhaps a less immediate association for the later generations. In the famous ad, known as Boy on the Bike (directed by Ridley Scott, no less), a boy is shown pushing his bike loaded with loaves up a cobbled street in a quaint Dorset village.3 Its enduring success undoubtedly rested on the reassuring, picturesque image of Britishness that the adverts conveyed. Although the reality of a mass-produced food company based in Macclesfield could not be further from the idyllic countryside setting, the ad nonetheless conjured nostalgic feelings that appealed to the general public.4 Golding taps into the same nostalgia as a “gateway to cultural identity and emotional intelligence”.

The English countryside already served as the setting for the wanderings and healing rituals of three nomadic brothers in Golding’s Bring Me to Heal (2021). This relationship with nature, or rather, the landscape, is equally central in Britannia. As noted by the artist, the landscape stands for British pictorial tradition, a legacy that is incidentally celebrated in the adjacent gallery rooms dedicated to the painters of the celebrated Norwich School. The peaceful and tranquil rural landscape of Southern England is also a key trope of Englishness and – by extension or generalisation – Britishness.

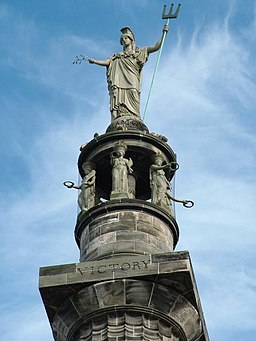

The title of the film and her nakedness qualify the woman as an allegorical representation of Britannia, though significantly diverging from its more traditional iconography. Devoid of her attributes such as the Corinthian helmet, the shield, and the trident or spear, she is no longer a maiden in her prime, but a mature woman who is more flawed than victorious. Instead of wearing a white garment with her right breast exposed, she is not nude but naked, exposed. Outside of time, her relationship with the natural elements, the hounds, the pigeons, is most ambivalent, at the same time wholesome and estranged.

‘Self-implication’ is a recurring theme in Golding’s artistic journey that is closely connected to his Rastafarian roots. In Rastafari philosophy, self-understanding is paramount to develop one’s identity but also engagement and agency in the world. In opposition to the false consciousness of oppressive institutions, InI consciousness, that is, the awareness of the Self and the other as being one, is the vehicle to the discovery of true knowledge. Cultural identity, in this sense, is a subject for a conversation that speaks a visceral, embodied language rather than normed communication.

In Chainmail (2016), Amartey Golding approaches another evocative nostalgic trope, mediaevalism. Chain mail garments encapsulate the duplicity of meanings associated with mediaeval nostalgia: from the tales of knights, castles, and princesses to the darker reality of serfdom, exploitation, and pillaging. More than the stuff of childhood fantasies, the mediaevalist revival is woven into the foundation myth of European nation-building. A metonymic reference, Golding’s chain mail represents the Janus-faced epoch of freedom and oppression. Norwich Castle, in this sense, becomes more than an exhibiting venue, its history being integral to Britannia. The imposing Norman castle whose construction was ordered by William the Conqueror epitomises both the acceptance of enforced power as well as the revolutionary spirit that led to Robert Kett’s Rebellion in 1549.

Britannia is a manifestation of Englishness imposed on the rest of the British nations. This embedded as well as debated national identity constitutes the point of departure for Golding’s retrospective gaze that works through the traumas causing present-day stress, anxiety, and pain. “Through the figure of Britannia, Golding explores ideas around how nostalgia and amnesia can function, and how these emotions might inhibit understanding and compassion.”5 Situated somewhere between collective memory and amnesia, nostalgia celebrates an acceptable image of the past – whitewashing the things that we are more ashamed of. By culturally reframing it, the artist embarks on a healing process that involves coming to terms with our historical traumas.

In Britannia, the landscape hints at a genre celebrated in British artistic tradition which incidentally finds a prime example in the works displayed in the museum that commissioned the film. Another seminal aspect in Golding’s oeuvre is the dialogue that the artist engages with the museum as the temple of memorialisation and national identity. In the short film Bring Me to Heal – St George (2021), the countryside is replaced by the rooms of the V&A where Golding’s Garment finds its significant place alongside the mediaeval and renaissance collections. As the body wig made of knotted human hair comes to life before the frozen stare of the silent statues, embodied by Black man who walks the gallery rooms and takes stock of centuries of (art) history. Like a suit of armour of sorts, the hair resembles a lion’s mane symbolising, by association to Rastafarian dreadlocks, confidence, boldness, and uprightness. Marvelling at a cast of Michelangelo’s David, the man stops to contemplate the Altarpiece of St George by the Master of the Centenar (Valencia, 15th century). Drawn by its beauty, the man is however struck by the violence and torture depicted in the scenes of martyrdom resonating with his own suffering. No longer objects for aesthetic contemplation, the works of art now tell a different, shared story of pain, trauma, and enslavement.

In 1955, a German émigré scholar, Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-1983), spoke to the British audience about the Englishness of English Art for the BBC Reith Lectures. The popular lectures were later expanded in a book whose dust jacket introduced it as an illuminating reading to discover the features of one’s national character through the eyes of others.6 Pevsner had been inspired by another account of the national character in British art written during the war, in 1942, by Viennese scholar Dagobert Frey.7 Paintings by Hogarth, Reynolds, Blake and Constable, the Perpendicular Gothic, and the Picturesque were, according to Pevsner, the quintessentially English expressions of a national artistic style that resonated with the unifying traits of “moderation, reasonableness, rationalism, observation and conservatism” but also “imagination, fantasy, irrationalism”.8

Turning the attention to English art was part of the adaptive strategy adopted by migrant scholars – Edgar Wind studying Reynolds or Frederick Antal researching Hogarth are but a few examples. In the aftermath of a world war, however, an investigation into English art may have been misconstrued for a glorification of national divisions. For this reason, Pevsner cautiously warned that his geography of art did not seek to establish the supremacy of one artistic civilisation, or to argue oversimplified, unchangeable national traits, but to draw a complex picture of polarities: “in the geography of art […] no simple statements must ever be expected. […] the history of styles as well as the cultural geography of nations can only be successful […] if it is conducted in terms of polarities, that is in pairs of apparently contradictory qualities.”9 But more importantly, Pevsner’s reflections were prompted by the fact that in the face of chauvinism on many other fronts, England’s self-confidence collapsed when it came to her “own aesthetic capabilities”.10

The sixth chapter on ‘Constable and the Pursuit of Nature’ deals with the tradition of landscape painting evoked in Golding’s Britannia. The study and pictorial interpretation stimulated by the English climate led painters to develop an “open and sketchy technique” that could capture the ever-changing atmosphere.11 Constable’s scientific attitude towards the observation of natural phenomena like cloud formation resonates with “that eternal quality of Englishness, the rational approach”.12 Between 1800 and 1840, continued Pevsner, England would lead the way towards atmospheric landscape in the works of Constable, John Sell Cotman, Richard P. Bonington, and David Cox. Their unifying qualities were “the intensity of feeling for nature combined with an unreal coherence of the surface, independent of the corporeal shapes lying as it were behind”.13

Did Pevsner’s reflections on Englishness resonate with the impact of the loss of imperial power in post-war Britain? At the time of the Reith lectures, national self-representation had to reckon with the process of decolonisation, anti-nationalism, but also the dawn of a new, multi-cultural Britain with the Windrush generation. The question of Englishness at the end of the British Empire was explored in a seminal 2005 book by Wendy Webster.14 Key mass-mediated moments in the post-war era, such as empire films, the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II (1953), and Winston Churchill’s funeral (1965), reinforced a narrative of national identity in which two different world views collided. The short-lived idea of ‘people’s empire’ uniting men and women across the Commonwealth, contrasted with the opposite image of a domesticated, quiet, little, white Britain that was hailed as a sanctuary threatened by migration and colonial wars.15 The other collateral issue was the way Englishness and Britishness were used as synonymous, as if England could speak for the rest of Britain – after all, Vera Lynn did not sing There’ll Always Be A Britain. As mentioned, Golding’s Britannia, too, emphasises this cultural conflation in the choice of music, the Hovis ad, which hints at the identification of Britishness with the rural South.16 The acquisitive museum embodied in the V&A rooms in Bring Me To Heal, on the other hands, show the less domestic, more global and imperialistic side of this identity.

Coda

R. Fry, Reflections on British Art (1934), p. 21.

“Patriotic feeling, when it affects the art-historian, shows itself always at once futile and ridiculous.”

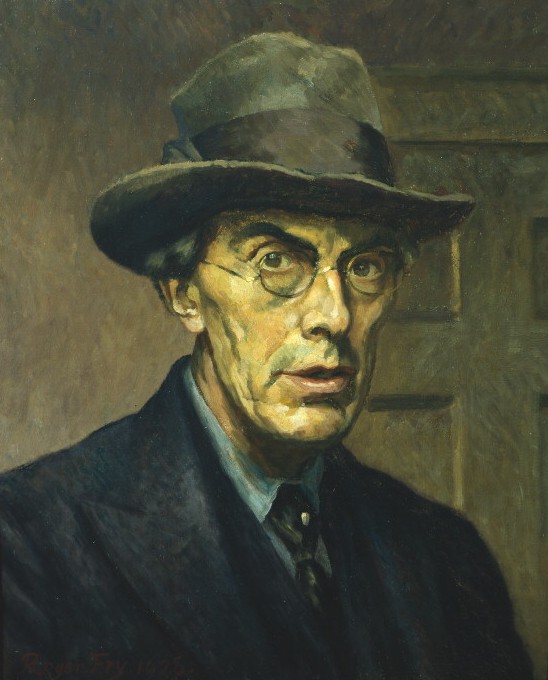

The English self-consciousness in praising their artistic achievements remarked by Pevsner can find a perfect example in the harsh opinions that Roger Fry (1886-1934) expressed after seeing The Great British Art Exhibition at the Royal Academy (1934).

Feeling that critic’s liberty to offer his honest views on the tribe’s idols was a sign of British open-mindedness in the face of the intolerance that was spreading across the Continent, Fry did little to temper his bluntness. The main cause why Britain did not have an artistic civilisation worthy of that name was an innate snobbism that led to dogmatically accept the canonised old masters. British artists were to blame for their “easy-going complacency and indifference” to the spiritual torment that yields great accomplishments. British patrons, in turn, were contemptuous and unimaginative, only favouring celebratory portraits or landscapes depicting their possessions.17 The first quarter of the 19th century, hailed as a moment of artistic splendour by Pevsner, was instead a missed opportunity: “by 1850, scarcely anything was left of this glorious promise; British art had sunk into a level of trivial ineptitude.”18 Philistinism, Puritanism and “gross sentimentality” dominated the British art scene for the rest of the century. Even Britain’s recognised excellence, landscape painting, was somewhat tepidly described as the the expression of the Englishman’s attachment to country life and his love of nature. Looking to Dutch models, the painters from the Norwich School, and John Crome in particular, succeeded in giving to their formula “a distinctively English sentiment”.19 But their downfall was always the failure to fully master plastic design.

Fry spoke even less enthusiastically of the nation’s hero, Turner. Too busy making things, that is, producing pictures, Turner did not have any time or desire to understand the outside world: “His vision was a means to his ends, to this business of making pictures. […] He knew how to pick out and underline the exciting passages and how to pass over the rest a vaporous vagueness which stimulated the feelings by its mysterious promises.”20 Britain’s only saving grace appears to have been Constable, the only English artist to have made a significant contribution to European painting – “an adventurer, a discoverer of the mysterious significance of his own experiences in front of nature”.21

The Middle Ages reimagined by the Pre-Raphaelite painters and in the buildings of the Gothic Revival was, lastly, dismissed as “whimsical aestheticism utterly divorced from life and from good sense”. Their nostalgia, according to Fry, though initially inspired by disinterested passion, offered but “an artificial shelter from the Philistine blizzard out of half-apprehended mediaeval notions and archaistic bric-à-brac.”22

Fry firmly believed that patriotism had no place in the history of art. But in the 1930s, the history of art in Europe was going in a different direction. German art historians endeavoured to defend their ‘blood and boundaries’ by defining the character of German artistic civilisation and celebrating the genius of Dürer or Gothic as a native style. To some extent, the British Art exhibition at the Royal Academy shared the same celebratory purpose.

Anticipating the London exhibition, Herbert Read (1893-1968) wrote an article on ‘English Art’ (another sweeping assimilation!). In search for the Englishness in English art, Read concluded that while a satisfactory “racial definition” may have been easier to find, art had her own way of “defying boundaries, whether land or blood”.23 Echoing Read’s words, British artists like Amartey Golding continue to defy those boundaries to reshape a more complex and inclusive Britannia.

- Amartey Golding, Britannia, 2023, 12’, film & solo exhibition, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, 30 September 2023 – 14 January 2024. ↩︎

- The artist’s quotes are taken from Britannia: In-Conversation with Amartey Golding and Dr Rosy Gray, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, 10 January 2024. ↩︎

- The advert was shot on Gold Hill in Shaftesbury (Dorset). ↩︎

- Boy on the Bike was also brilliantly lampooned by comedian Ronnie Barker in 1978 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJi_5T0jSnA). ↩︎

- https://www.amarteygolding.com/copy-of-in-the-comfort-of-embers ↩︎

- N. Pevsner, The Englishness of English Art (London: The Architectural Press, 1956). ↩︎

- D. Frey, Englisches Wesen im Spiegel seiner Kunst (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1942). ↩︎

- Pevsner 1956, p. 186. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 18. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 19. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 150. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 152. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 161. ↩︎

- W. Webster, Englishness and Empire. 1939-1965 (Oxford: OUP, 2005). ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 8: “Englishness was increasingly invoked as an intimate, private, exclusive identity that was white. In much of this imagery, it is hard to imagine that Britain had ever occupied a position as a colonial power or continued to embrace a global identity through the transition from empire to Commonwealth.” ↩︎

- Interestingly, Golding’s first choice for a soundtrack was Vera Lynn’s We’ll Meet Again (1955). ↩︎

- R. Fry, Reflections on British Art (New York: MacMillan, 1934), p. 24. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 90. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 113. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 127-8. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 139. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 108. ↩︎

- H. Read, ‘English Art’, in The Burlington Magazine 63 (1933), 369, p. 242. ↩︎

Leave a comment