David Anderson, ‘Museum Education in Europe’, in: The Journal of Museum Education 19 (1994), pp. 3-6

Cultures, not objects, are our real concern. It is the cultural space around and between objects that gives them their meaning and makes it impossible for museums to avoid a social and political role. To ignore or deny this role, despite all the difficult problems it entails for us, would be to evade a fundamental public responsibility.

This post was inspired by Alice Procter‘s Uncomfortable Art Tours and more extensively, her work on museums’ critical engagement with their politics of display, colonial past, and their role in racial erasure.1

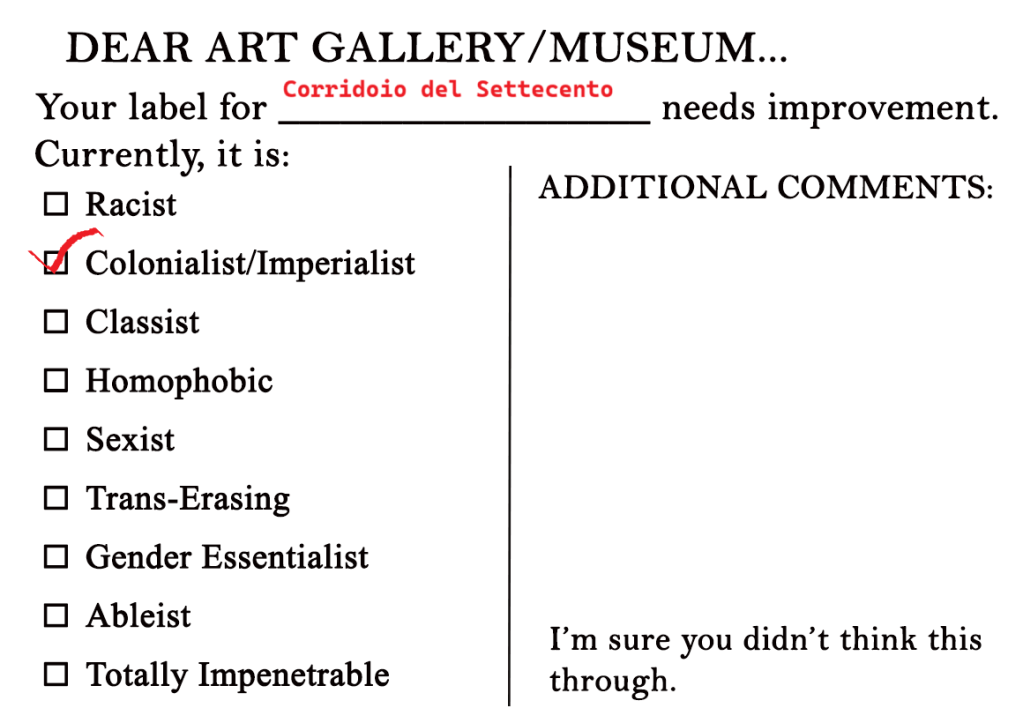

#fixyourlabels is an ongoing project launched by Alice Procter to raise awareness on how museums (un)intentionally avoid coming to terms with their uncomfortable histories. Today, museums can benefit from a wider range of mediation devices (audio guides, touch screens, etc.) made available by digital technology. Labels, however, continue to be an easier, more accessible, immediate, and economic way to inform, engage, and influence visitors. More than a source for technical information, labels provide a critical framework that inevitably changes the way viewers will look at an object. The name of its maker will not only determine the pedigree but also the attention the museum-goer will devote to that object – as well as their discretionary amount of awe and chin-stroking.

During a recent trip to Naples, I had the opportunity to visit the Capodimonte Museum on a busy Sunday morning when it was open to everyone free of charge. Dubbed the Italian Hermitage, Capodimonte houses the remarkable and extensive collection of works of art from the Farnese Collection later expanded by the Bourbon dynasty, together with the acquisitions as a residence of the House of Savoy. The museum develops on two floors with the picture gallery coexisting alongside the stately rooms of the royal residence.

On the second floor, the Corridoio del Settecento (‘Eighteenth Century Gallery’) was recently redisplayed with works previously in storage that illustrate the multi-faceted history of the museum’s collections as well as the taste exemplified in collecting practices.2 Exquisite dinner sets from Meissen and the Royal Manufacture of Capodimonte are displayed alongside tapestries from the Real Fabbrica, vedute of Naples, and portraits of Bourbon Kings in an arrangement reminiscent of period rooms. A set of Spanish muskets qualifies the second room devoted to the casini di caccia, i.e., hunting lodges dedicated to venery for kings and noblemen such as the summer residence of Capodimonte.

Let us focus on the collection of Indigenous artefacts which serves as centrepiece. Collectively labelled as “ethnographic objects from the South Seas”, they include weapons, hunting instruments, and religious objects, some of which originally belonged to James Cook and were later donated to King Ferdinand IV by the British ambassador, Lord Hamilton (1730-1803). Other “exotic” (sic.!) objects come from the collection of Cardinal Stefano Borgia (1731-1804). While the decontextualised display as decorative objects in a stately residence can be explained as a curatorial choice to recreate the way in which they would have been historically exhibited, the scant and generic information about them seems hardly appropriate. But perhaps worse is the way the acquisition of and interest in Indigenous material and artistic cultures is described in the museum label.

“The 18th century was marked by major geographical discoveries, with new maritime routes being opened, for which the British navy played a central role. The objects and weapons from Oceania collected by Captain James Cook, explorer and cartographer of the British merchant navy, came into the royal collection as a gift to King Ferdinand IV from the diplomat and volcanologist Lord Hamilton (1730-1083), the English ambassador to the Neapolitan court (1764-1800). Other ‘exotic’ artefacts come from the 18th-century collection of Cardinal Stefano Borgia (1731-1804), a cultivated collector and the Secretary of the Propaganda Fide Congregation. In this role, he was able to gather a diverse range of materials from the Catholic missions around the world as specimens of far and exotic lands following an erudite and encyclopaedic interest for the history of civilisation. The collection was purchased by King Ferdinand in 1817, after a long negotiation that had started with Joachim Murat, the King of Naples during the French rule from 1808 to 1815.”

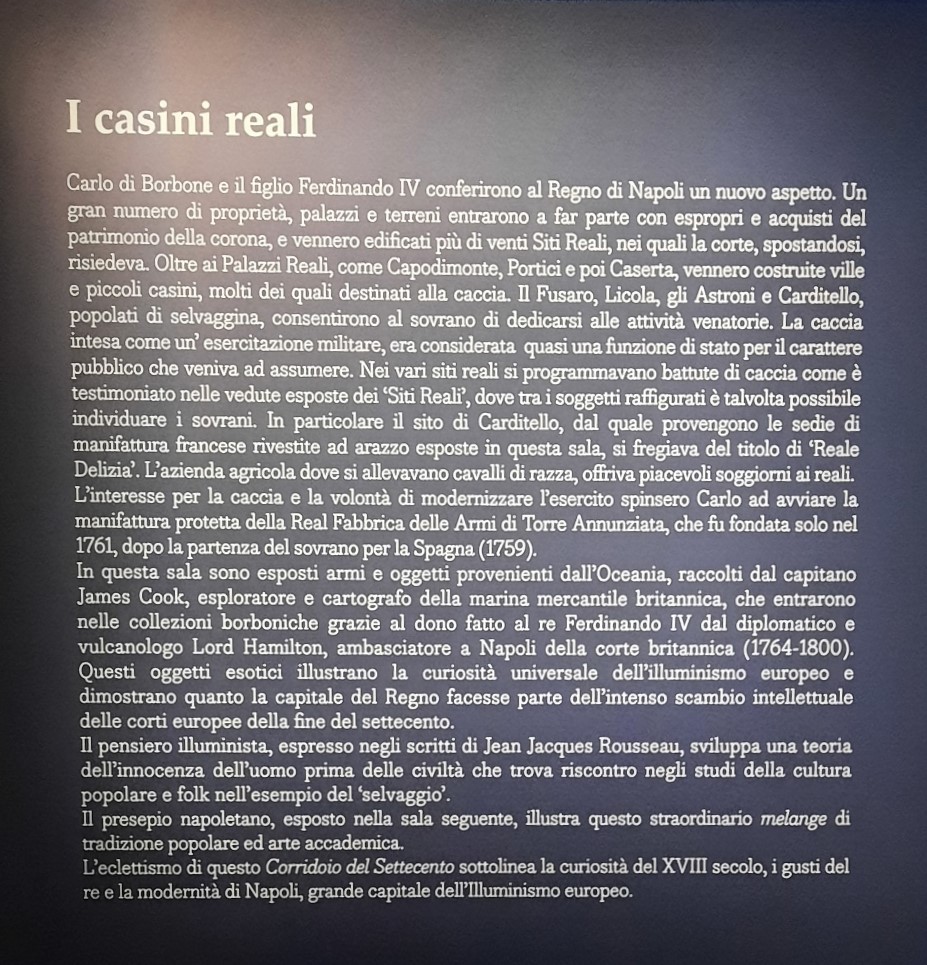

The exhibition panel introducing visitors to the room illustrates the passion for hunting sports and the associated court rituals and fashions. Concerning the “exotic objects” (this time, without quotation marks in the original text), they are presented as an illustration of “the universal curiosity of European Enlightenment” and Naples’ central part in “the intense intellectual exchange between European courts at the end of the 18th century”.

A feature of many cabinets of curiosities, natural specimens and artefacts from far away civilisations undoubtedly spoke to the quest for encyclopaedic knowledge that marked the age of Enlightenment. Unfortunately, that is only half of the story. No mention is made of the concurrent quest for colonial supremacy, racial superiority, the genocide of Indigenous populations, the slave trade, and the scramble for economic and political control. James Cook, instead, is described as an explorer and a cartographer and Stefano Borgia’s erudite interest is in the “history of civilisation”. Perceiving the connections of Italy – or the Kingdom of Naples – to imperialism as indirect may be conducive to a sense of diminished responsibility. At this day and age, however, it is no excuse for a museum not taking accountability or whitewashing history. Moreover, one wonders if the lack of detailed information on each object is an oversight due to the anonymity of their authors and a lesser artistic pedigree. Jean Jacques Rousseau’s myth of the noble savage – continues the label – is reflected in an overarching taste for folk art as a means to rediscover an uncorrupted state of nature pre-civilisation, thereby summarising the fraught upon notion of primitivism. Paraphrasing the concluding remarks in the introductory panel, this eclectic display exemplifies the King’s intellectual “curiosity”, Naples’ “modern” taste and its prominent place in European Enlightenment. When unproblematised, presenting objects acquired through colonial expeditions aimed at establishing socio-economic and religious supremacy as tokens of Western cultural sophistication is deceptive, historically incorrect, and dangerous. Genocidal crimes have been (and are) committed in the name of a monolithic notion of “civilisation” – a word whose use should be duly contextualised.

In the early 20th century, the trailblazing curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and arguably the father of visitor studies, Benjamin Ives Gilman (1852–1933), addressed the standards of visitors’ experience of museum collections. In studying ways to prevent what he called “museum fatigue” (i.e., visitors’ physical exertion), Gilman addressed the problem of labels. Admittedly, his preoccupations with the ease of access were more physical than educational. In the 1918 book Museum Ideals of Purpose and Method, Gilman listed seven reasons why labels could be problematic and ultimately detrimental – and not all of them related to positioning or legibility. 1) Labels could be unavailable – especially for objects grouped together. 2) They could be an unsightly addition to the object intended for pure contemplation. 3) They could be impertinent in implying the viewer’s ignorance. 4) They could be fatiguing adding to the labour and time spent in the museum. 5) They could be unsatisfactory as a mere factual list of names and places. 6) They could dull the interest in looking at the objects. 7) They could be misleading as they are necessarily succinct. This last point is worth quoting at length: “We often cannot tell the close truth on a label without making it impracticably cumbersome. A proportion are forced to perpetuate misinformation. Again, a label emphasizes that part of the content of the object which is describable in words – its motive or use – to the exclusion of the rest of its content – always more important.”3

Would the “close truth”, in this case, be “impracticably cumbersome”?Understandably, historic arrangements centre on the visual impact of the display as a whole as a testament to a certain period, collecting taste or zeitgeist, rather than focusing on its single pieces. Yet, poor factual information is here compounded by an incorrect and biased critical framework. A more sensitive and inclusive wording in lieu of outdated and prejudiced terms like “exotic” and more or less subtle “exclusions” would have sufficed to avoid misleading information. Alternatively, more context could have been provided using other communication devices – a QR code directing to a page on the museum website, for instance. In the hustle and bustle of families and individuals flocking to the museum on a Sunday morning coming up to these last rooms, their critical awareness needed a little jolt. Left unstimulated and unchallenged, their attention drifted to the following room drawn to an actor impersonating Maria Carolina of Austria complaining about King Ferdinand’s infidelity.

According to a recently proposed alternative ICOM definition, museums should be “inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue” whose purpose is “to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social injustice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.”4 The plural in “understandings” is pivotal just as the singular in “civilisation” is problematic. As visitors, we have a duty to remain vigilant and call out supremacist and non-inclusive narratives especially when adopted by an educational institution.

Dear Museo di Capodimonte, I’m sure that you didn’t think this through, but please consider the impact of your colonialist/imperialist labels.

- See Alice A. Procter, The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk about it (London: Cassell, 2020) and her podcast the exhibitionist ↩︎

- https://capodimonte.cultura.gov.it/depositi-di-capodimonte-storie-ancora-da-scrivere/ ↩︎

- Benjamin I. Gilman, Museum Ideals of Purpose and Method (Cambridge MA: Riverside Press, 1918), p. 321. ↩︎

- https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-announces-the-alternative-museum-definition-that-will-be-subject-to-a-vote/ ↩︎

Leave a comment