Watering places for Victorian pleasure-seekers

“Everyone delights to spend their summer’s holiday down beside the side of the silvery sea” – as the famous music hall song goes. When Mark Sheridan wrote it in 1907, British seaside resorts had become popular with holidaymakers from all walks of life.1

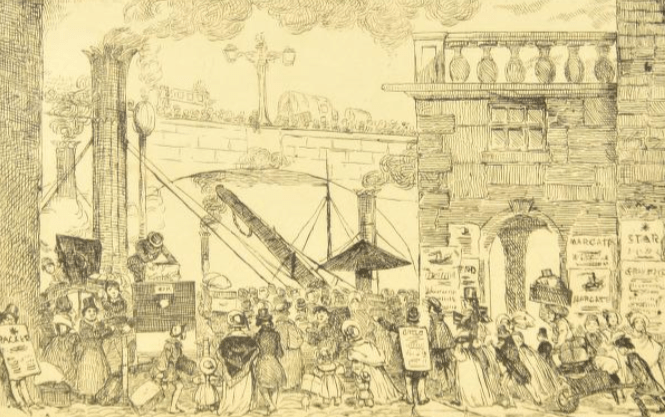

‘Starting’ and ‘Sea-Bathing’, plates from A. Crowquill, A Guide to the Watering Places with Illustrations (London: J. & F. Harwood, 1833)

Coastal towns, also known as ‘watering places’, were initially attractive for the curative benefits of sea-bathing. An amusing guide (1833) penned by Alfred Crowquill [nom de plume for the Forrester brothers – Charles Robert (1803-50) and Alfred Henry (1804-72)] ironically described the different types of people that flocked to watering places. On doctor’s orders, the renovating, invigorating sea air brought together the “lean spinsters, with slender pittances” as well as families, but also the “imbiber of foreign wines and spirits”, the “black leg and gambler”, “old bachelors”, and especially, “the burly bathing-women, enveloped in blue flannel garbs […] ducking timid ladies and kicking infants”.2 Whether for health or recreation, in the course of the 19th century, watering places went from being the purview of the upper classes to almost a mass phenomenon – as recorded by Edwin Lee in 1859.3 As travelling improved, British spas could not compete with the quality of spring water on the continent and those who could chose to go to France and Germany, instead. “Recreation and society” being, on the other hand, what most visitors were looking for, the watering places that could provide varied forms of entertainment were preferred.4 Staple activities included sea-bathing, walking on the promenade, riding donkeys, collecting shells, enjoying the sand, and visiting local monuments. For all manner of conditions, sea-bathing was often recommended by physicians for its remedial effects.

The arrival of the railway in the 1830s and 40s ensured easier and quicker travel to coastal towns. Initially holidaymakers mostly belonged to the middle class, but as train tickets became more affordable, they were joined by working-class families as well. The introduction of bank holidays in 1871 further prompted people to spend a couple of days on the coast. Alongside the all-time favourites, such as Blackpool, Whitby, Margate, Brighton, Eastbourne or Llandudno, many fishing villages on the British coast eventually became booming tourist attractions.

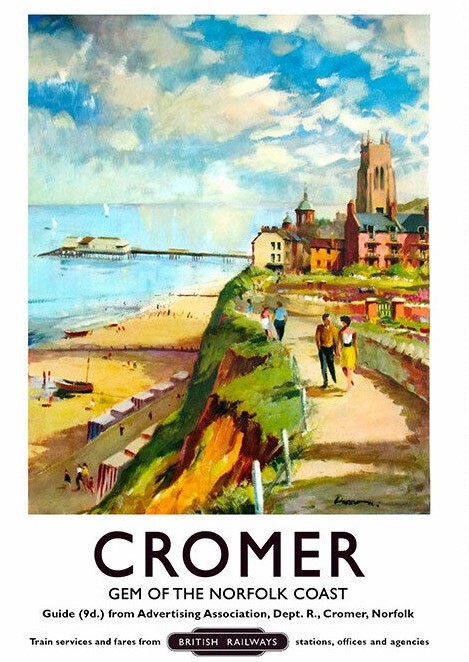

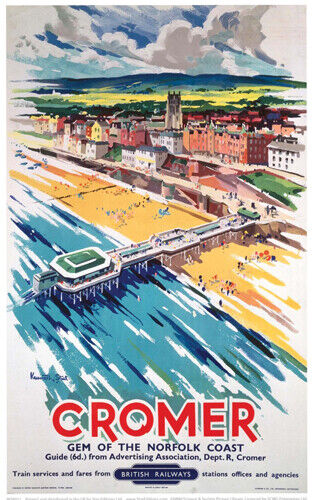

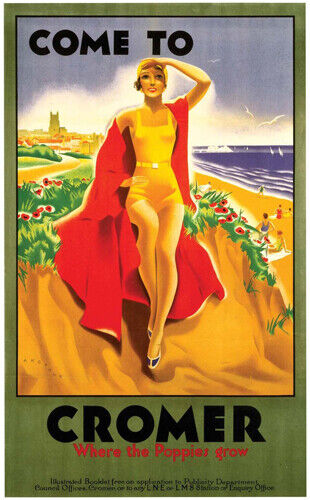

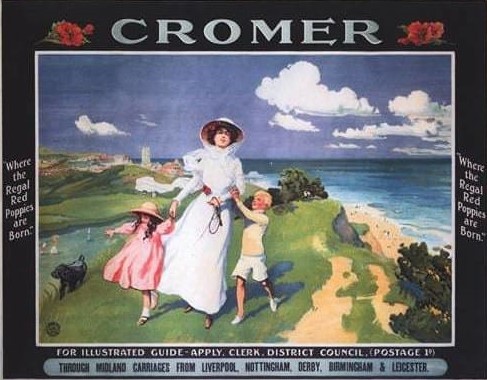

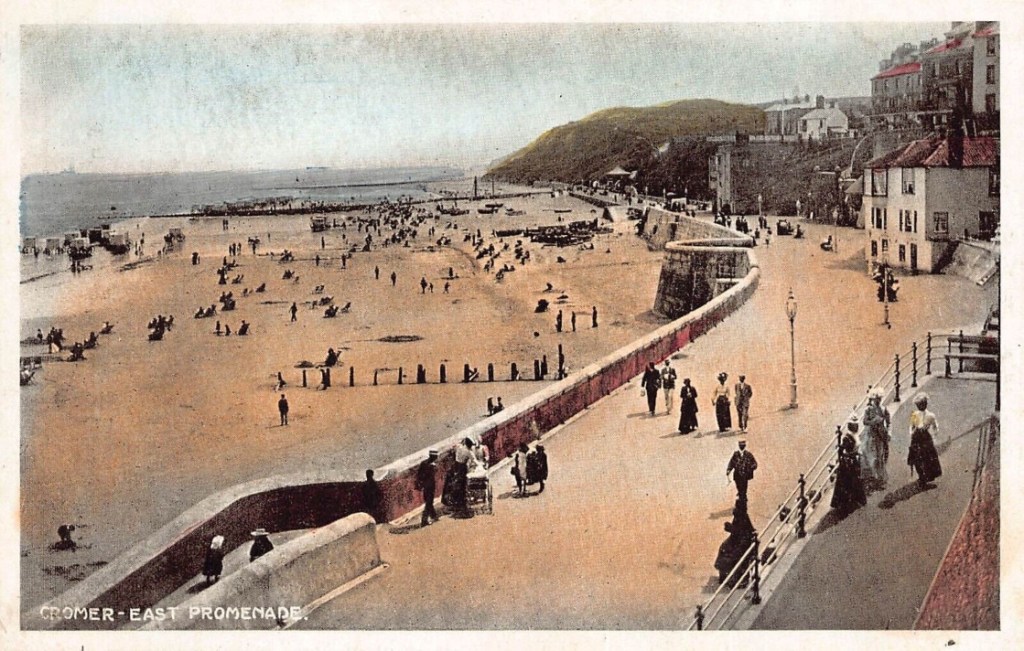

On the North Norfolk coast, Cromer was a fishing town that developed into a beloved seaside destination during the 19th century. To mark #EnglishTourismWeek2024, I decided to follow this transformation as reported in two guide books at the beginning and the end of the century.

Any account would begin from a historical overview of the pre-existing village of Shipden mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086) – now lost to the sea. Early records of Cromer (originally Crowmere) dated back to the 13th century and in 1565 the town was listed as a landing place with a pier and counted 117 householders. Trading with the Baltic region, Iceland, and Greenland, Cromer slowly lost its economic importance over the centuries as a result of the general decline of the wool industry in Norfolk. While the first visitors are recorded in 1785, Cromer began to be frequented by ‘strangers’ at the start of the following century.

Writing in 1800, Edmund Bartell (1759-1829) painted a detailed picture of the town on the East coast. Alongside more famous places like Ramsgate, Brighton or Weymouth, Cromer deserved to be considered for the pursuits of health or leisure, not least for its outstanding natural beauty.5 Once a place of consequence, Cromer was then only a small village mainly dependent on fishing. Bartell warned that houses were “indifferent” and the rents high, though some lodgings offered a fine sea view and were most desirable.6

Visitors, however, often did not have the time, nor inclination, to look for lodgings. What Cromer lacked was a “well-conducted Inn” and, though hazardous for its seasonal nature, investing in such a business was the only way the town could “stand a chance of rivalling some of the more celebrated bathing places”.7 Food, and fish in particular, was highly praised: crabs, whitings, cod-fish and herrings “caught to the finest perfection”, and above all, lobsters were the most celebrated catch.8 Little was offered in the way of entertainment: “There are no places of public amusement, no rooms, balls, nor card assemblies. A small circulating library, consisting chiefly of a few novels, is all that can be obtained; but still for such as make retirement their aim, it is certainly an eligible situation.” The beach, on the other hand, was ideal for sun-bathing, with roomy bathing machines. Its “fine firm sand, not only renders the bathing agreeable, but when the tide retires, presents such a surface for many miles as cannot be exceeded. […] The cliffs in many parts are lofty and well broken, and their feet being for the most part composed of strong blue clay, are capable of making considerable resistance to the impetuous attacks of the sea.”9

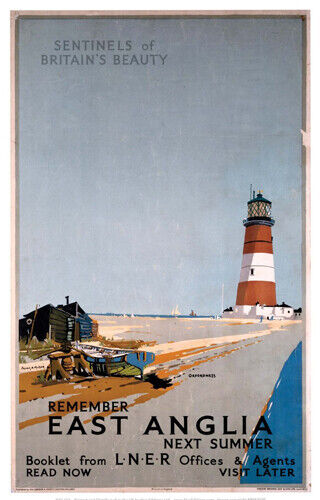

Walking and riding, contemplating the ever-changing seascape provided the chief source of enjoyment. The Lighthouse on a ridge to the east of the town “commands an extensive sea-view, the inland prospect is confined by a range of hills forming an amphitheatre around it.” Extending the walk a little further, visitors could reach “a pleasing view of the village of Overstrand.”10

The present Lighthouse was built in 1833, Bartell referred to the pre-existing tower dating 1719.

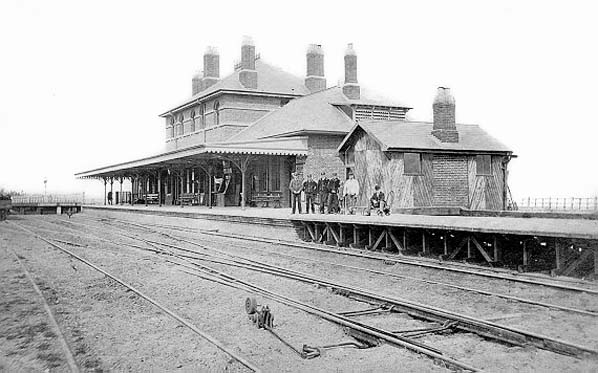

By the end of the century, Walter Rye (1843-1929) wrote of a profoundly changed town in Cromer Past and Present (1889). “Of late years the trade of the town dwindled away to nothing, a little timber and coal being imported by beaching the ships and carting away their contents at low tide; but this is quite extinct now that the railways have been opened. The only real business the natives now do is to attend to those who visit it as a watering place”.11

In June 1845, the Great Eastern Railway connected London Liverpool Station to Norwich Thorpe Station, and in 1877 the rail service arrived to Cromer. Although Rye looked back to the days when coaches ran between Cromer and Norwich with nostalgia, there were undeniable advantages to travelling by train – even if the stunning view from the hill-top station was the only one he could enumerate.12

Published only a few years earlier, The Land of the Broads (1885) by biographer Ernest R. Suffling offered a comprehensive, practical guide for the tourists visiting the beautiful waterways of the region, the Broads, which included a stop in Cromer.

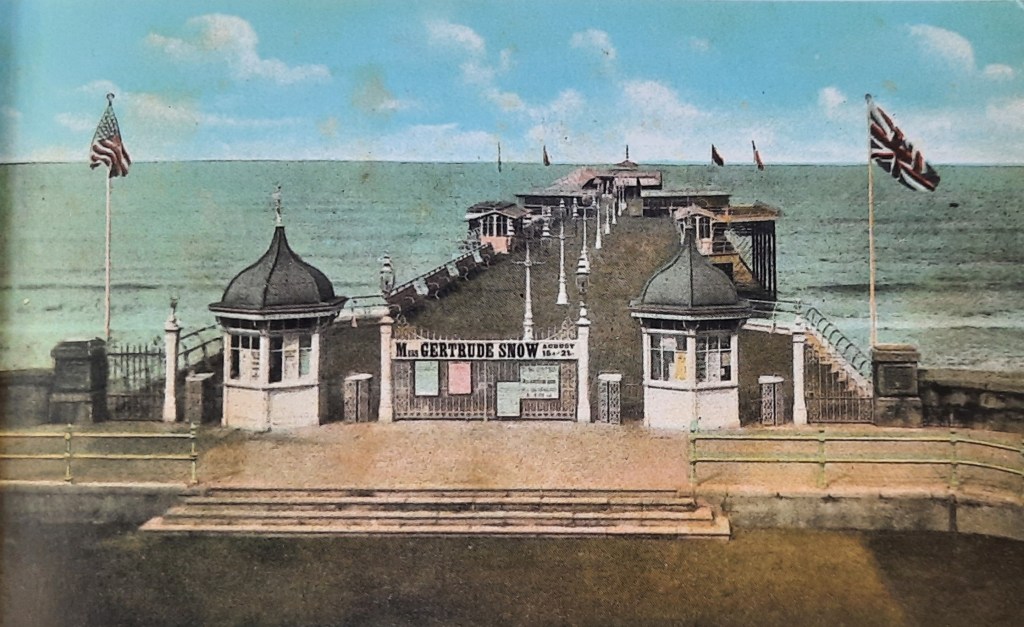

“Cromer, which is fast becoming a favourite watering-place, stands on the cliffs, in a hollow between hills which environ it on three sides. […] The Jetty, which is a stumpy little affair, about 200ft. long, is the great promenade during the summer months. But the glory of Cromer is its beautiful sands, which are so firm that as many as a dozen tennis courts may be seen marked out on them at one time.”13

In Victorian and Edwardian times, seafront gardens and promenades were an essential part of the social rituals and entertainment performed in watering places. In Cromer, the first sea wall was built in 1836 with further expansions to the west in the following decade, and to the east in 1893-4. From the bastions, a system of ramps and steps led to the Promenade Esplanade where, ice-cream in hand, visitors could take leisurely strolls and enjoy spectacular views of the sea. Jetties and piers ceased to serve a merely practical purpose and became places filled with amusements frequented by pleasure-seeking holidaymakers. The first iron pier was erected in Ryde (Isle of Wight) in 1814, and other prominent examples include Brighton’s Chain Pier (1823) immortalised by Turner, the impressive Southend Pier (1829) and Eastbourne Pier (1870). In Cromer, a wooden jetty was documented as early as 1391 and its maintenance mentioned up to the 16th century. The underwhelming wooden structure that Suffling referred to was built in 1846 and dismantled in 1897 after being severely damaged. In June 1901, the jetty was replaced by a 500-foot iron Pier that became the focal point of Cromer – boasting an end-of-pier Pavilion Theatre (now the oldest of its kind in Europe). Built as a seaside residence in 1820, the Hotel de Paris was converted into a hotel in 1830 and extensively remodelled by George Skipper (1856–1948) in 1874. Other swanky hotels included the Tuckers, the Metropole, the Marlborough and the Clifton Hotel.14

To the busy Prom, some people preferred more quiet, solitary walks on Cromer Ridge. Upon visiting the North Norfolk coast, journalist, playwright and travel writer Clement Scott (1841-1904) fell in love with the area and poetically captured its essence in a piece for The Daily Telegraph titled ‘Poppy-Land’ (1883). From the Lighthouse cliff, Scott poignantly observed the stark contrast between the metronomic schedule of the holidaymaking crowd and the calm, tranquil countryside surrounding Cromer:

It was on one of the most beautiful days of the lovely month of August, a summer morning, with a cloudless blue sky overhead, and a sea without a ripple washing on the yellow sands, that I turned my back on perhaps the prettiest watering-place of the east coast, and walked along the cliffs to get a blow and a look at the harvest that had just begun. […] Below me, as I rested among the fern on the lighthouse cliff, there they all were, digging on the sands, playing lawn tennis, working, reading, flirting, and donkey-riding, in a circle that seemed to me ridiculously small as I looked at it from the height. In that red-roofed village, the centre of all that was fashionable and select, there was not a bed to be had for love or money; all home comforts, all conveniences to which well-bred people were accustomed, were deliberately sacrificed for the sake of a lodging amongst a little society that loved its band, its pier, its shingle, and its sea. […] A mile to the left there was not a footprint on the beach, not a foot-fall on the grassy cliff. Custom had established a certain fashion at this pretty little watering-place, and it was religiously obeyed; it was the rule to go on the sands in the morning, to walk on one cliff for a mile in the afternoon, to take another mile in the opposite direction at sunset, and to crowd upon the little pier at night. […] No one thought of going beyond the lighthouse; that was the boundary of all investigation. Outside that mark the country, the farms, and the villages were as lonely as the Highlands.

- I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside by Mark Sheridan (1907), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9DmwX9ZdQA ↩︎

- A. Crowquill, A Guide to the Watering Places with Illustrations (London: J. & F. Harwood, 1833), pp. 4-5. ↩︎

- E. Lee, The Watering Places of England (London: John Churchill, 1859), p. 1. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 5. ↩︎

- E. Bartell, Observations upon the Town of Cromer: Considered as a Watering Place, and the Picturesque Scenery in Its Neighbourhood (London: John Parslee, 1800), p. iv: “Few people are altogether insensible to the beauties of a fine country, – few things to a contemplative mind are capable of giving that satisfaction which the beauties of nature will afford.” ↩︎

- E. Bartell, Observations upon the Town of Cromer: Considered as a Watering Place, and the Picturesque Scenery in Its Neighbourhood (London: John Parslee, 1800), pp. 5-6. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 8. At the time, however, the Red Lion had been an inn for at least three and a half decades. It was first licensed to Sherman Cutler in 1766. ↩︎

- Ibid.: “Indeed, coming to Cromer and eating lobsters are things nearly synonymous.” ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 12-3. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 19. ↩︎

- W. Rye, Cromer Past and Present (Norwich – London: Jarrold and Sons, 1889), p. 78. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 147: “I will say nothing of the railways. No doubt they are convenient to certain people, and since the coaches have ceased to run, even those who hate have to use them. […] The Great Eastern station has one redeeming point, it certainly has the finest view from it of any station I have ever seen. The line ceases on the crest of a hill, and the station stands like a fort commanding the village and sea below.” In 1887, the more central Cromer Beach station was opened. ↩︎

- E.R. Suffling, The land of the broads. A practical guide for yachts-men, anglers, tourists, and other pleasure-seekers on the broads and rivers of Norfolk and Suffolk (London: L.U. Gill, 1885), p. 188. ↩︎

- The archive images of Cromer Lighthouse, Promenade, Beach, Jetty and Pier pictured in the article are taken from H. Magdin, Cromer Through Time (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2009). ↩︎

Leave a comment