Feminism & Art in the Victorian Age

As Women’s History Month draws to a close, we are reminded of Virginia Woolf’s foundational feminist tale A Room of One’s Own (1929). The book has often been quoted as the starting point for all considerations on the marginalisation of female creative geniuses who shared the faith of Shakespeare’s fictional sister, Judith. Despite her talent, she was precluded the education that her brother received. Forced to flee an arranged marriage, she moved to London seeking fortune on the stage, but her talent was not well received. Finally, she committed suicide after she was impregnated by a theatre impresario. Judith embodied a gendered corporeality antagonistic to creativity, in other words, shaping the myth of “murdered female creativity, internalised as self-inflicted death”.1 Oppression and lack of financial independence, that is, a room of one’s own, prevented women from becoming great writers, according to Woolf.

“Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size. […] Whatever may be their use in civilized societies, mirrors are essential to all violent and heroic actions.”2

But a time will come, Woolf hoped, when women will have the “habit of freedom” and the courage to write exactly what they think, to stand alone before reality and be great writers.

Woolf’s compelling analysis of how women had been prevented from becoming great writers resonates with Linda Nochlin’s celebrated article ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ (1971) published at the height of the women’s liberation movement. Laying the foundation for later feminist art theories, Nochlin believed that the answer to a male-dominated artistic pantheon was that women were denied the same academic training imparted to their male colleagues. By not being allowed to attend nude classes, female artists were de facto excluded from the higher rank of history painting and confined to the lower-regarded genre painting. Sociological and institutional barriers were the reasons why there had been “no women equivalents for Michelangelo or Rembrandt, Delacroix or Cézanne, Picasso or Matisse, or even in very recent times, for de Kooning or Warhol, any more than there are black American equivalents for the same”. A white-dominated world and patriarchal society canonised art as the product of a few male geniuses:

“The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education – education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals.”

Taking inspiration from the show Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 due to open next May at Tate Britain, I decided to look at the first pioneering attempt to write an all-female history of art: Ellen Clayton’s two-volume English Female Artists (1876).

Today some may associate Victorian society with prudishness and bigotry, but it was also the time the saw the birth of the feminist movement and an increased access to education – at least for women from the middle and upper class. Against this backdrop, it was not wholly unusual for women to write about art. The Anglo-Irish critic Anna Brownell Jameson (1794-1860) published extensively on art history, travels, and feminism. Her prolific bibliography includes two popular handbooks on public and private art collections in London – Handbook to the Public Galleries of Art In and Around London (1842) and Companion to the Most Celebrated Private Galleries of Art in London (1844), Memoirs of the Early Italian Painters (1845), and the essay ‘The House of Titian’ (1846).3 Her friend Lady Elizabeth Eastlake [née Elizabeth Rigby] (1809-1893), wife of the National Gallery director Sir Charles, was an art historian in her own right. Lady Eastlake regularly contributed to the Quarterly Review – reviewing, amongst other things, Modern Painters by John Ruskin – and wrote Five Great Painters (1883), a book about Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Dürer. As the translator of Gustav F. Waagen, Franz Kugler, and Johann D. von Passavant, she was responsible for disseminating German art history in England.4 Another female art historian, Mary P. Merrifield (1804-1889), devoted her efforts to studying the techniques employed by the old masters editing a translation of Cennino Cennini’s A Treatise on Painting (1844). Together with the following books The Art of Fresco Painting (1846) and Original Treatises, dating from the XIIth to XVIIIth Centuries on the Arts of Painting (1849), her work was especially influential for the Pre-Raphaelite painters and paved the way for conservation studies. Across the Atlantic, Elizabeth F. Ellet (1818-1877) published a trailblazing survey of European female artists from antiquity to the 19th century – Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (1859). Ellet’s intent was to show what women artists could accomplish in unfavourable conditions. The struggles and trials they endured, their “persevering industry”, courage and resolution, and eventually, their “well-earned triumphs” should inspire other women to achieve “honourable independence” and “lead to a higher general respect for the powers of women and their destined position in the realm of Art.”5

Left to right: Anna Brownell Jameson, after David Octavius Hill, and Robert Adamson, carbon print, 1843-1848; published 1928; London, National Portrait Gallery; © National Portrait Gallery, London. Anna Brownell Jameson, after David Octavius Hill, and Robert Adamson, carbon print, 1843-1848; published 1928; London, National Portrait Gallery; © National Portrait Gallery, London. Elizabeth (née Rigby), Lady Eastlake, by David Octavius Hill, and Robert Adamson, calotype, 1843-1848; London, National Portrait Gallery; © National Portrait Gallery, London. Mary P. Merrifield, unknown author, ca 1870. Engraving of Elizabeth Ellet, New York Digital Library Image

In the same year as Ellet’s Women Artists, back in Britain, another remarkable art scholar was petitioning the Royal Academy for full admission of women as students. Dublin-born Ellen Creathorne Clayton (1834-1900) came from a family of wood engravers and did some illustrating herself before becoming an accomplished writer of novels, and an art historian. Alongside novels and children’s books, she published biographical accounts of famous female figures such as Notable Women (1859), Women of the Reformation (1861), Queens of Song (1865) and Female Warriors (1879). Clayton’s pièce de résistance was the two-volume biography English Female Artists (1876) covering the life and work of female painters from the 16th century to the contemporary age.6

“Our native paintresses […] have left but faintly impressed footprints on the sands of time. They do not glitter in the splendour of renown, like their sisters of the pen or of the buskin.” Reduced to “scarce an incident beyond the commonplace in the brief record of their public or private career”, compiling a biography of female artists was an arduous task that the author undertook with a scholarly as well as a political intent (vol. I: 2). An ardent advocate for ladies’ rights to an artistic education, Clayton’s commitment rang clear from the dedication of her book to the painter Elizabeth Thompson, “in testimony of admiration for her genius”. Genius was an epithet normally reserved for male talents while gifted women artists could be praised for their industriousness and dedication, at best. While Clayton did not hesitate to use the word for deserving sister artists, in Lady Waterford’s biography, she juxtaposed a man’s genius to a woman’s “graceful fancy” (vol. II: 339).

Beyond the typical anecdotal facts and observations on temperament, Clayton paid close attention to the socio-economic circumstances in the way of women becoming accomplished artists such as adequate training, remuneration, and societal expectations. She also offered acute observations on collecting, taste, and attributions – reporting the accredited opinion as well as her own insight. Witnessing the collecting mania and the proliferation of connoisseurs of her age, she commented:

“The picture dealers reaped a golden harvest by the mania. They imported or manufactured mock Titians, forged Raffaelles, spurious Coreggios; renamed every old Italian painting with some high-sounding master’s name; dubbed every hard dry German picture a Holbein.” (vol. I: 80)

Clayton duly cited the literature she consulted for English Female Artists, particularly for the first historical part. Abreast of more recent publications, Clayton’s bibliographical index is a testament to the success of the biographical genre in Victorian Britain. The list of authorities offered a comprehensive overview of nascent British art historiography: James Dallaway’s Anecdotes of the Arts in England (1800),Michael Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (1816), Allan Cunningham’s The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters (1830), Matthew Pilkington’s General Dictionary of Painters (1857), Gustav Waagen’s Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1857), Ellen’s Women Artists (1859), Walter Thornbury’s British Artists (1861), Henry Ottley’s A Biographical and Critical Dictionary of Recent and Living Painters and Engravers (1866), Horace Walpole’s Anecdotes of Painting in England (1871), Samuel Redgrave’s A Dictionary of Painters of the English School (1874). Interestingly, Clayton cited William Hazlitt’s artistic essays but not John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (1843) – though she referred to it in the book. Despite this wealth of biographies, English female painters had been vastly overlooked.

“The historians, the letter-writers, the biographers, even the diarists, have been persistently mute regarding the sayings and everyday doings of eminent Englishwomen. […] Of her female artists, the muse of English history has been curiously reticent. We feel as if in presence of a circle of wax models; we see the outward form, may chance to come upon traces of much extolled work, but the difficulty is to discover what the silent, toiling student, seated tranquilly in front of her easel, is really like” (vol. I: 66-7).

Clayton conceded that attempting to trace the origins of the English national school of art was a thankless business. During the Middle Ages, warfare left no time for the cultivation of the arts and, except for book illumination, patrons often resorted to foreign talents. As a consequence, (male) artists did not attain a high social status and this was even more true for women, typically confined to their homes or the convent. Being precluded any formal training, the only sisters who pursued an artistic path followed in the footsteps of a family member, at least “until these more pleasant latter days” (vol. I: 8).

“Not one solitary instance exists before the sixteenth century of an Englishwoman who attempted any pictorial work except tapestry” (vol. I: 4). The irony that this artistic rebirth should happen under the patronage of an iconoclast like Henry VIII was not lost on Clayton. During his reign, the first recorded female artists were Flemish-born Susannah Hornebolt (1503-ca. 1554) and Lavinia Teerlinck (1510s-1576), both daughters of court painters.

Elizabeth I’s lacking support for the visual arts confirmed the general rule that “women in power have done little to foster painting and sculpture” (vol. I: 9). But the situation changed with Charles I’s patronage and avid collecting, when “the dawn of refined taste brightened almost into perfect day” (vol. I: 15). Enjoying the King’s favour was Anne Carlisle, a portrait painter and a copyist of Italian masters who worked in Van Dyck’s studio. She was credited with being an “ingenious lady” (vol. I: 19), a designation that Clayton observed was usually used to describe females in literature, science and art.

Although ‘regrettably’ a foreigner, the resplendent Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) was the jewel in the crown of this age.7 Her adventurous life could be summed up as a romance by George Sand; a “beautiful, gifted, much admired artist, who won every shade of gold opinion save respect” (vol. I: 21). Like many other intelligent women, Artemisia “had contrived to fetter herself by a most unhappy, ill-assorted marriage.” (vol. I: 23). Albeit not an edifying one, Clayton warned, Artemisia’s biography was a testament to her accomplished career: “she was always prosperous, always on the best of terms with herself and everybody else, making plenty of money, living like a princess, admired, courted, smiled on by Pope and by king, by princes and by great masters.” (vol. I: 29).

The Interregnum of Oliver Cromwell was a dark age for the arts branded as sin and idolatry. Out of the “little sisterhood of artists” patronised by Charles II, Mary Beale (1633-1699) stood out as its leader. Beale was a portraitist praised for her “persevering industry and conscientious study” (vol. I: 40). Trained by Sir Peter Lely, she assiduously copied Italian masters and refined a “masculine” (!) drawing technique (vol. I: 43). Not just a talented artist, Mrs Beale was an “irreproachable wife”, an “excellent mother” (vol. I: 45). Clayton could not escape the conventions of her time whereby those were a woman’s ultimate achievements, though a tinge of irony can be detected in remarking that she lived a life full of “sweetness and dignity and matronly purity which is next to impossible for a biographer to render ‘interesting’” (vol. I: 51).

Poet and painter Anne Killigrew (1660-1685) was characterised as “a beauty, a wit, a verse-writer, an agreeable painter, maid of honour to a royal duchess standing next the throne, almost perfect in character, sweet and gracious in her manner” (vol. I: 59). Mary Delany (1700-1788) was crowned “one of the most graceful of those hooped and powdered beauties adorning the resplendent Georgian era” (vol. I: 96). Aside from a glamorous and eventful social life, Clayton commended her crayons, paintings, shellwork, furniture designs, and embroidery: “a graceful, talented, industrious Englishwoman; an artist ingrained; one quick to perceive beauty […]; glowing with aesthetic fire and aspirations.” (vol. I: 142).

The biography of Frances Reynolds (1729-1807) showed the advantages and disadvantages of being born into the trade. Sir Joshua’s younger sister became an accomplished miniaturist despite her brother’s contempt. Ironically, one of the founding members and first President of the Royal Academy and the author of the Discourses on Art celebrated as an eloquent teacher, Joshua Reynolds was a terrible mentor to his sister. Much to his displeasure, Frances copied his paintings in watercolour, but he refused to give her any instructions. In Clayton’s unforgiving characterisation, Reynolds was, in fact, a bad teacher to all his students: “always trying to struggle towards the light himself, perpetually experimentalising, consciously ignorant of the rules of drawing, discovering by laborious degrees the secrets of painting, rarely permitting even his pupils to see him at work” (vol. I: 153). Because of her brother’s overt depreciation, Frances pursued her artistic inclinations in secret without his guidance. Cayton speculated that he probably did not understand much about miniature painting anyway. Perhaps not gifted with originality, Frances was however a “careful and painstaking worker” and always tried to win her brother’s affection (vol. I: 154). Joshua Reynolds, on the other hand, appeared socially amiable, but he could be cruel in his judgement of people and prone to rage.8 “Sir Joshua had a little discouraging, sneering way of under-estimating his sister’s judgement, which had naturally a chilling effect upon her timorous nature”. Frances’ determination to learn oil painting was met with extreme displeasure, so much so that “she was obliged to study almost by stealth” (vol. I: 196). Making no mystery of her dislike towards Joshua Reynolds, Clayton revelled in describing his first clumsy attempts at drawing and his beginnings as an unimaginative and unremarkable portrait painter. It was through gritted teeth that Clayton acknowledged his brilliant talents that had brough on a “new epoch to arise in English art history” (vol. I: 158).

Maria Hadfield Cosway (1760-1838) was another artist whose career was held back by a man. Educated in Rome, she was acquainted with the likes of Pompeo Batoni, Raphael Mengs, Joseph Wright of Derby and Henry Fuseli. Her husband Richard Cosway’s credentials, on the other hand, only amounted to being an errand boy for William Shipley, picking up a scanty knowledge of painting and working his way with high-society patrons through flattery and patient manipulation (vol. I: 318). After they married, Maria had the misfortune of completing her training with her husband who kept her secluded until she became a polished lady fit to enter society. Clayton thought that her miniatures were equal to her husband’s, “poetic in feeling” and “facile in execution” (vol. I: 321). Worried that her paintings would have fetched a higher price, Richard Cosway however forbade Maria to work for money. The Cosways were described as a couple of socialites: while the husband dallied with royals and nobility, “the wife beamed, roulade, curtsied, bowed, and played her mimic part with elegance and grace” (vol. I: 324). Eventually, Mr Cosway fell out royal favour for sympathising with French Revolutionists and subsequently travelled to the continent. Husband and wife would continue to lead separate lives, as Maria accompanied her brother to France and Italy for three years leaving her child in her husband’s care in London. After the death of their only child, Mr Cosway’s health never recovered and when he died, Maria Cosway moved to Italy and settled in Lodi.

During the reign of George III, amateur drawing and painting became fashionable activities in the education of young ladies. Moreover, a knowledge of the old masters was a necessary requirement for refined, cultivated gentlemen, too. The social implications of this renewed interest in the arts were noted by Clayton: “to sit to a fashionable portrait-painter was an agreeable morning lounge; the ‘Academy’ was already beginning to be a pleasant rendezvous” (vol. I: 336). Along with embroidery, drawing offered an “innocent and inoffensive recreation” suitable for ladies of the highest rank (vol. I: 338). The Queen and the Princesses Royal led the way for a swathe of female amateur artists who, ranked with their professional sisters, were “as fine brilliants set in gold” (vol. I: 358). As a result of their liberal patronage, by the end of the 18th century, more than a dozen female artists were enrolled as honorary members of the Royal Academy.9

Catherine Blake [née Boucher] (1762-1831) was described as the ideal wife to husband William, “fulfilling in letter and in spirit the vows of love and obedience she had softly breathed at the altar” (vol. I: 370). William Blake had taught her wife to draw, and her works were according to Clayton undistinguishable from her husband’s. Though gifted, she received very little artistic credit. Living for her husband’s success, she ran the household and served as his assistant – tinting and binding his engravings. Draughtswoman, illustrator and wax-modeller Mary Ann Flaxman (1768-1833) concluded the period that “passed as a dream of Fair Women; graceful, noble figures, laden with highest and purest gifts. A golden circlet of stars, the like of which no other land could show” (vol. I: 378).

Approaching the 19th century, Clayton’s political agenda becomes more overtly clear. At the beginning of the century, the most distinguished names were to be found among portrait painters, “never before or since have so many English lady artists obtained such honours in a most difficult branch” (vol. I: 385). With the introduction of photography, miniature painting, a field that had long been the purview of women artists, was fast becoming obsolete. The academic path, on the other hand, was far from clear. A talented portrait artist like Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793-1872), for instance, was denied a place as Academician.10 Brimming with indignance, Clayton blatantly accused the Royal Academy of studiously ignoring “the existence of women artists, leaving them to work in the cold shade of utter neglect. Not even once has a helping hand been extended, not once has the most trifling reward been given for highest merit and industry” (vol. I: 388). Accidents of circumstances and birth, “aided by courage and talent” (vol I: 389) would gradually open the doors of the Academy to female students. But the struggle to break the glass ceiling was going to be a long haul:

“In free, unprejudiced, chivalric England, where the race is said to be to the swift, the battle to the strong, without fear or favour, it is only by slow, laborious degrees that women are winning the right to enter the lists at all, and are then viewed with half contemptuous indulgence.” (vol. I: 389)

Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807) and Mary Moser (1744-1819) had been the first two women to be admitted as Academicians of the Royal Academy. The “half contemptuous indulgence” or ambivalent acceptance Clayton referred to was obvious in Johann Zoffany’s painting The Academicians of the Royal Academy (1771-2) where Kauffmann and Moser were only depicted in effigy because there were male nude models in the room.11

Other organisations did far more for the advancement of sister artists. The Society of Female Artists, in particular, was established in 1855 to encourage and promote the work of female painters, sculptors, and craftswomen. Its annual exhibitions were a welcome opportunity to display their paintings. Women water colourists could also count on the support of the Society of Painters in Water Colour (the forebear of the Royal Watercolour Society) created in 1804 with the purpose of endorsing an artistic practice that was discriminated by the Royal Academy.12 Other venues that regularly featured works by female artists included the Dudley Gallery, the British Institution, Portland Gallery, but also temporary events such as the South Kensington Great Exhibition (1851) and the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition (1857).

The “first important opening to women to share in the art educational privileges accorded to their brothers” was when the Royal Academy finally accepted female students (vol. II: 84). Following a petition endorsed by Charles Eastlake, Anne Laura Herford (1831-1870) was the first woman to enter the RA in 1860. Cunning deception was involved as her admission pieces were cleverly signed with the initial ‘L. Herford’, an ambiguity that ensured the recognition of her merits. Enduring the discomfort of being the only representative of her sex and constant object of curiosity and criticism would be the price to pay for a long time: “opposition, prejudice, wonderment, the showers of pros and cons, gradually faded away, and in these privileged later days a fair proportion of female students are regularly admitted” (vol. II: 3).

The second tome of Female Artists reflected the growing number of women pursuing an artistic career in the latter half of the 19th century. The chronological order of the first volume was replaced by genres for the contemporary age: figure, landscape, portrait and miniature, flowers, fruit and still lifes, animals, humorous subjects, decorative arts, and amateur painters. This division, incidentally, gives us a hierarchical picture of the genres that were more typically practiced by female artists. Their success stories, on the other hand, offered a more encouraging perspective of the social progress made. Being married to a famous painter, for instance, was no longer a grievance for Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema [née Epps] (1852-1909) who exhibited her works alongside her husband’s.

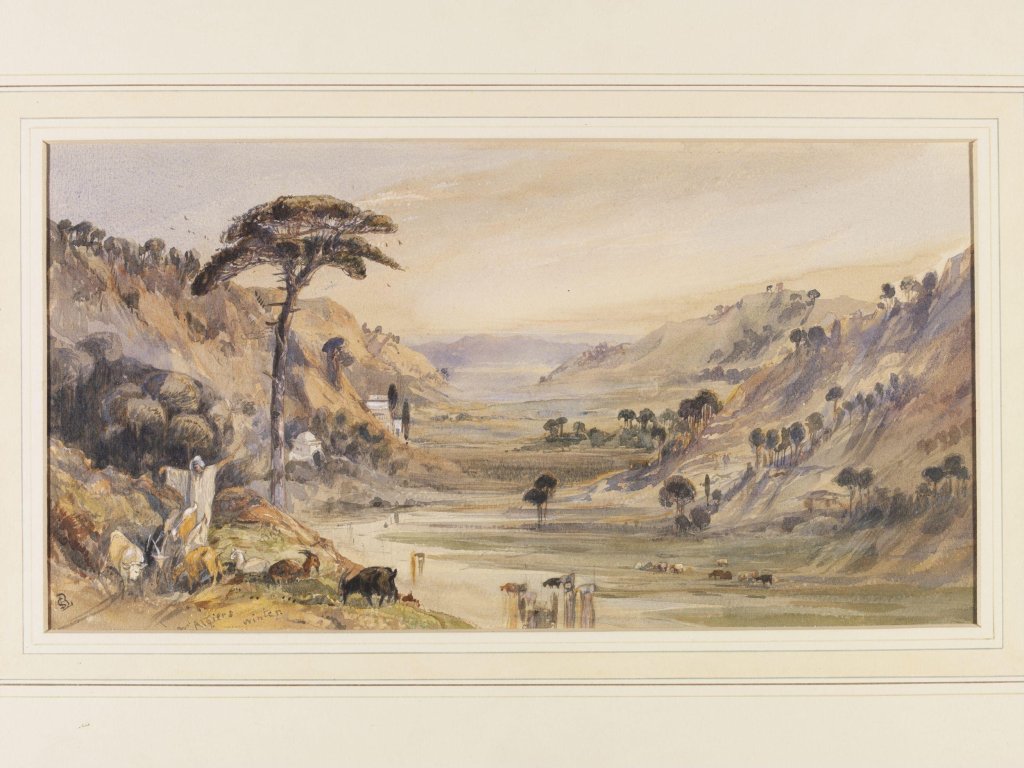

The education offered by museum collections in Britain and across Europe and the institutional training now made available to female students meant that women no longer needed to come from a family in the trade to become artists. Edith Mary Arendrup [née Courtauld] (1846-1934), for instance, was allowed to study the human figure despite the common prejudice against a woman attending nude classes. After attending the South Kensington School, she settled in Egypt in 1872 where she married a Danish army officer and lived there until his death in 1875. Clayton’s detailed description of the wonderments as well as Western commonplaces about Egypt reflected the typical fascination with the East of those times. Her praises for the “inexhaustible feast for the eye” that the ‘Orient’ could provide echoed the impressions of many European artists.13 The Orientalist fantasy was based on the idea of a country existing outside of time that allowed the artistic imagination to live in the Biblical past. The difficulties in sketching in the open air or obtaining models for studio work (either too greedy or too timid) resonated with other contemporary sources: “You are the object of overwhelming attraction to a population never too busy to spend any length of time in staring, crowding, and otherwise inconveniencing the unlucky sketcher” (vol. II: 18-9). Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1819-1881) was another artist who travelled to Egypt, the Middle East and Persia. Few artists “admired more intensely the grand Oriental types of beauty, the magnificence of costume, the magical splendour of colours there ever present” (vol. II: 105). Clayton’s stereotyped characterisation of the “mystical region” once more insisted on the discomfort of open-air study and the prying crowds (vol. II: 103-4). The picturesque tones used by Clayton to describe the Italian scenes painted by Margaret Backhouse [née Holden] (1818–1888) perfectly exemplified the Orientalisation of the Southern Europe.

Florence Claxton (1838-1920) was remembered for being the first woman to work for an illustrated paper – an activity hitherto considered unladylike for it involved “a very unpleasant amount of hurry, bother, downright drudgery, and night work” (vol. II: 45).

Alongside the achievements of many women artists, Clayton however underlined that the prejudiced culture against young girls learning art still lingered and “drawing was almost rigorously tabooed in most instances” (vol II: 70). To the ladies who managed to surmount these difficulties, having to study surreptitiously or in a “desultory, half-instructed way” (vol II: 71), Clayton paid the greatest credit. Eliza Bridell Fox [née Florance] (1824-1903) was a self-taught portraitist – “left for years to struggle alone and unaided” (vol. II: 82). To help other women, she later started an evening class for life drawing where students could draw undraped models.14 Louise Jopling (1843-1933) was forced to take up music instead of art, and as a married woman, babies (“that truly feminine impediment”) and a limited income kept her occupied (vol. II: 108). Unbeknownst to Clayton, Jopling defied the odds and would go on to become one of the most prominent female painters of the Victorian age and the first woman to be admitted to the Royal Society of British Artists (1901).

Women who came from or married into artistic families certainly found an easier path as their training was facilitated by travels and the “surrounding influences” of illustrious masters, and intellectual frequentations (vol. II: 123-4). This was the case for Ellen Gosse (1850-1929), Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s sister-in-law, Catherine Madox Brown Hueffer (1850-1927) and Lucy Madox Brown (1843-1894), both daughters of Ford Madox Brown and the latter also married to William Michael Rossetti. Sarah Setchel (1803-1894) was encouraged to cultivate her interest in art since a young age by her father John Frederick. When Sarah wished to direct her efforts to history painting, her father would be less supportive and convinced her to stick to domestic scenes – a genre more congenial to female artists. The Momentous Question was Setchel’s most famous watercolour which fetched an unprecedented sum for a lady artist – much to Clayton’s delight.

Elizabeth Murray [née Heaphy] (1815-1882) was hailed as the leading artist of modern times. As the daughter of a court painter, she was able to begin her early studies on her father’s collection of anatomical figures and casts. In Rome, she trained under the Director of the Académie Française, the celebrated artist Horace Vernet, no less. In Venice, she was charmed with the Venetian school of colouring. An adventurous life, promising career, and a marriage to the British Consul took her to Malta, Gibraltar, Tangiers, Turkey, Greece, and America. “Few women have led a more eventful life, travelled more, or seen more varied scenes, from palaces to gipsy quarters, in the four quarters of the globe” (vol. II: 115).

No lady artist since Angelica Kauffmann roused as much interest as Elizabeth Thompson (1846-1933), whose life is described in heroic terms – “admired, envied, extolled, spitefully or critically depreciated” (vol. II: 140). Showing promising gifts already in her youth, Thompson attended the Kensington School of Art before she continued her studies in Florence and Rome. A measure of her success was the furore surrounding her works on display at the Royal Academy that once warranted police intervention. Clayton’s endorsement of Elizabeth Thompson, moreover, resounded in the dedication of Female Artists which referenced her famous history painting The Roll Call (1874).

Landscape artist Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827-1891) was a leading figure of the feminist movement. Clayton commended her activism for the political rights of women, their education, and the law affecting the property of women. The author of the renowned Brief Summary of the Laws of England concerning Women (1854), Barbara Bodichon brought a petition before Parliament that was signed, Clayton recalled, by prominent ladies in literature, art, and science, such as Anna Jameson, Mary Howitt, Harriet Martineau, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The petition would be crucial in the approval of the Married Women’s Property Act (1882).

Landscape, miniature painting, fruit and flowers were genres extensively frequented by women. Animal painters were considered a lesser branch of the profession. Decorative artists had been popular only in the past few years and included very few women. Even more interesting is what Clayton remarked about the last group of the humorous designers, a category to which she belonged:

“Among the attributes specially claimed by Man is a sense of Humour. Woman may be allowed to possess Wit, but except in the case of farce or burlesque actresses, when she is simply patronizing the fancies of a man, she is denied any perception of Humour. For the defence it may be urged that Humour is a quality scarcely coveted by the ladies. They like to be admired for wit, archness, piquancy, even sarcasm, or any similar attribute that may be slightly tinged with a soupcon of the comic – but Humour, as a rule, they willingly relegate to those who care to claim it. Wit is fine and elegant: wit shines and scintillates in drawing-rooms and boudoirs, but Humour may run the risk of stepping over the boundary lines of vulgarity” (vol. II: 319).

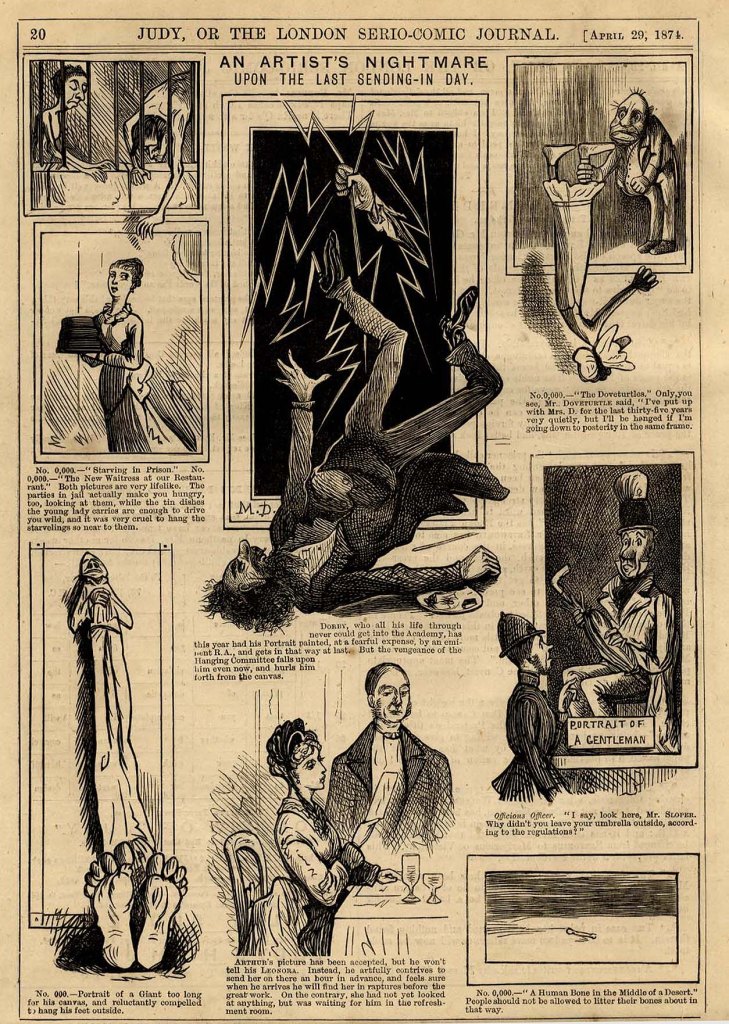

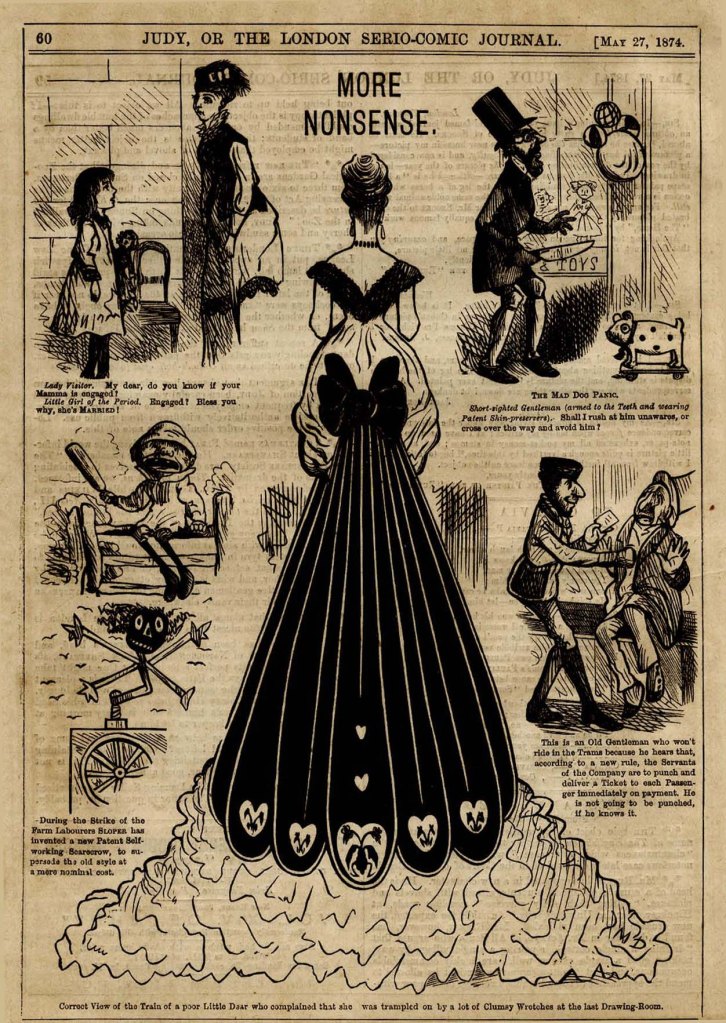

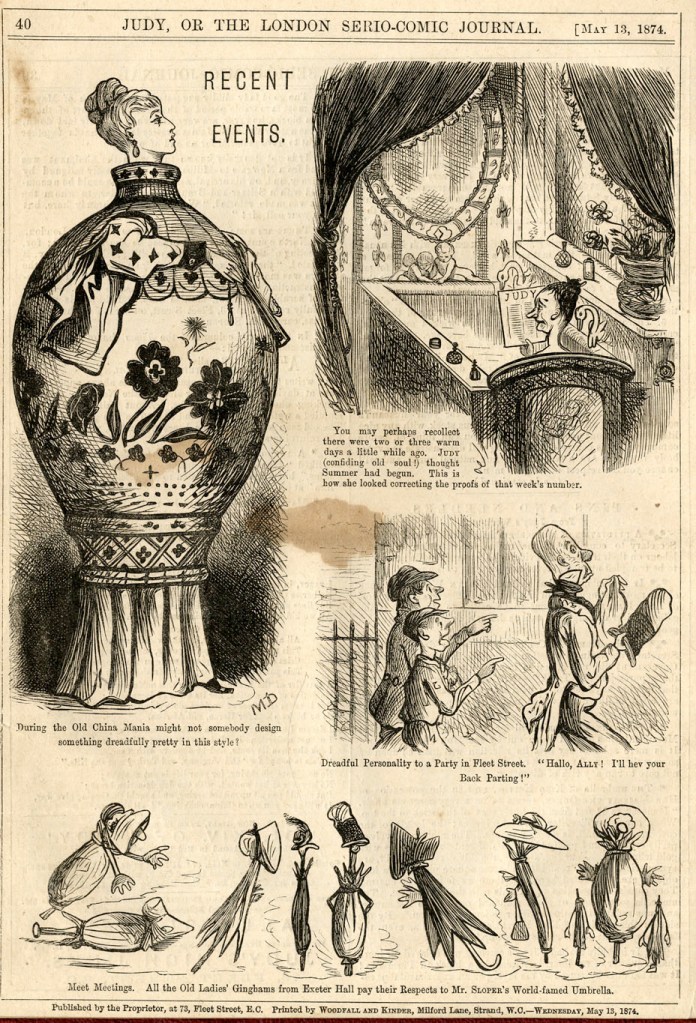

Georgina Bowers (1836-1912) was the first female humourist to be professionally recognised and, to that date, the only woman to have drawn for the satirical magazine Punch. Clayton however thought that her designs displayed more wit than humour and that she excelled in the spirited portrayal of horses and dogs. “To her own regret, she finds herself a sketcher when she desired earnestly to take rank in a far higher line of art. But she holds a distinct place of her own” (vol. II: 323). According to Clayton, French-born actress Isabelle Émilie de Tessier (1847-1890), better known as Marie Duval, was the most talented cartoonist of her time – “the others are undoubtedly witty and graceful, but rarely provoke laughter” (vol. II: 333). Her figures ranged from humorous to grotesque and her drawing often intentionally incorrect contributed to their comical effect. About the character ‘Ally Sloper’ that she created for Judy, Clayton wrote: “Nothing could be more irresistibly droll than ‘Ally Sloper’, absurdly comic, with an undercurrent of serious reflection, sometimes with a touch of strange pathos. […] Austere morality forbids approval of the villanies and subterfuges of the droll old scamp, yet somehow a smile will relax the features of Justice herself, where a frown should mark displeasure and discouragement.” (vol. II: 332)

Marie Duval, illustrations for Judy (1874)

The periodical Judy exceptionally employed the services of most of the lady humourists mentioned in Female Artists. Among them was also Ellen Clayton who included an autobiographical entry to this section. Eleanor Creathorne Clayton was the eldest daughter of artist Benjamin Clayton and Mary Grahame. Her artistic lineage counted her great-grandfather and her father’s sister, Caroline Millard, one of the few female artists in Ireland. Eleanor moved to London when she was seven. Trying to imitate her father, she precociously scribbled with pen or pencil. In her teenage, she started a comic weekly for which she wrote and made humorous designs. Later, she would also write and illustrate children’s books. When she resolved to pursue an artistic career, she attended the schools at the National Gallery, the British Museum, and the Dulwich Gallery, where she befriended other sister artists like Eliza and Mary Anne Sharpe and Laura Herford. Temporarily relinquishing her artistic pursuits, she published a series of biographies for young ladies while continuing to produce etchings, sketches, still lifes, and humorous designs. In between publications such as Notable Women and Queens of Songs, she returned to copy paintings at the National Gallery and the Louvre. Then she began to contribute to London Society and other illustrated periodicals like Judy and published a novel in three volumes, Cruel Fortune (1865). All the time producing sketches, drawings, and watercolours for “commercial houses” (calendars, valentines, conversation cards, etc.), Clayton described herself as possessing a certain “facility for sketching” and an “eye for colour” (vol. II: 329).

The biographies in Clayton’s book passionately tell the stories of many women who fought for a room of their own. Feminist art theory would have to wait another hundred years to come of age thanks to efforts of Linda Nochlin, Ann Sutherland, Germaine Greer, Griselda Pollock, Roszika Parker and Julia Kristeva, to name a few. Particularly fitting is Greer’s definition of women’s artistic career as an ‘obstacle race’ in which they had to overcome “self-censorship, hypocritical modesty, insecurity, girlishness, self-deception, hostility towards one’s fellow-strivers, emotional and sexual dependency upon men, timidity, poverty and ignorance.”15 Beyond the rediscovery of forgotten female artists, Griselda Pollock and Roszika Parker led the way in exposing the underlying values, assumptions, silences, and prejudices that make art history a male-dominated ideological practice. In this sense, women’s “reduced access to exhibition, professional status and recognition” chronicled in Clayton’s book, ultimately signified their exclusion from the power of producing “the languages of art, the meanings, ideologies, and views of the world and social relations of the dominant culture.”16 The broader questions that Clayton could not openly ask would be left to the future generations of feminist art historians to address:

“Why has it been necessary to negate so large a part of the history of art, to dismiss so many artists, to denigrate so many works of art simply because the artists were women? What does this reveal about the structures and ideologies of art history, how it defined what is and what is not art, to whom it accords the status of artist and what that status means?”17

- Cf. G. Pollock, ‘Feminist Mythologies and Missing Mothers. Virginia Woolf, Charlotte Brontë, Artemisia Gentileschi and Cleopatra’, in ead., Differencing the Canon. Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London – New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 129-31. ↩︎

- V. Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (Oxford: OUP, 1998), pp. 45-6. ↩︎

- Cf. A. Holcomb, ‘Anna Jameson: The First Professional English Art Historian’, in Art History 6 (1983), 2, pp. 171-87. ↩︎

- Cf. E. Eastlake, The Letter of Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake, ed. by J. Sheldon (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2009). ↩︎

- E.F. Ellet, Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (New York: Harper and Brothers publishers, 1859), p. vi. ↩︎

- E.C. Clayton, English Female Artists, 2 vols. (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1876). Cf. also M. Begoña Lasa Álvarez, ‘Women Artists and Activism in Ellen Clayton’s “English Female Artists” (1876)’, in Oceánide 12 (2020), pp. 37-44. ↩︎

- Even well into the 19th century, Clayton found it mortifying that few lady artists were of direct English descent (vol. II: 135). ↩︎

- “Joshua was genial, pleasant, sensible, kindly; troubling himself little about vexatious trifles; mentally and in manner always serene, equable, and sagacious; estimating, perhaps, rather highly the pomps and vanities; revelling in the pride of life; delighting in fine company; calm and practical. But if he could pleasantly purr, he could also scratch. He had a galling, cruel way of throwing stinging remarks at people for whose opinion he cared nothing; he could blandly sneer; he did not value religion, and it was difficult to access to his real self. He was cold, and made few professions of affection, even to those he liked, and could walk into a rage, though few knew it” (vol. I: 154-5). ↩︎

- Clayton mentioned the names of Ann Ladd, Mary Benwell, Mrs Grace, Mary de Villebrune, Catherine Read, Miss Beatson, Maria Morland, Catherine Bell, Mary Betrand, Elizabeth Johanna Collins, Mary Spilsbury, Anna Jemima Provis, and Mary Black. ↩︎

- “Truth, firmness of touch, brilliancy of colouring, both in oil and in water colours, were her leading points of excellence” (vol. I: 387). ↩︎

- A. Vickery, ‘Hidden from History: the Royal Academy’s Female Founders’ (2 June 2016) ↩︎

- Clayton mentioned that Louisa, Eliza, and Mary Anne Sharpe were prominent members of the Water Colour Society. ↩︎

- See ‘Basking in the Orientalist Afterglow. William Holman Hunt’s The Afterglow in Egypt and the Staging of Otherness’ ↩︎

- “Female students having experienced in its full bitterness the difficulty of thoroughly studying the human figure concealed by its habiliments” (vol. II: 83). One of the class attendees was Laura Herford. ↩︎

- G. Greer, The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux 1979), p. 11. ↩︎

- G. Pollock and R. Parker, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981). ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 132-3. ↩︎

Leave a comment