“For the first time, photography freed the hand from the most important artistic tasks in the process of pictorial reproduction – tasks that now devolved solely upon the eye looking into a lens.”

W. Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (1939)

The possible dire consequences of AI on all forms of creative expression are a very current concern. Not to mention the implications of image manipulation on journalism and political polarisation. Yet, the connotations of this debate in many ways reflect the cultural disquiet brought on by photography when it was first introduced.

Despite the undeniable advantages for art historians, some more than others were initially wary of the quality and reliability of photo reproductions. Another problem looming on the horizon, again resonating in our digital age, was that people grew accustomed to look at images instead of directly experiencing the original works.1

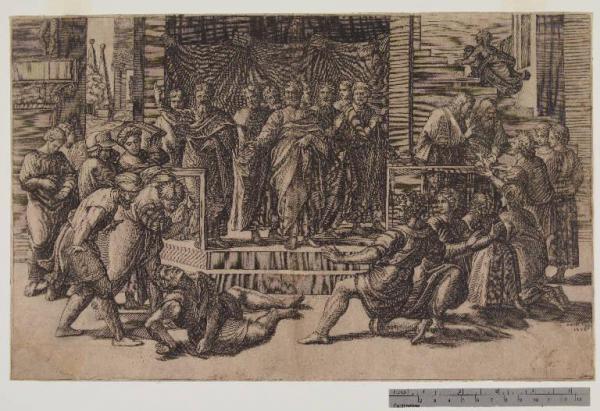

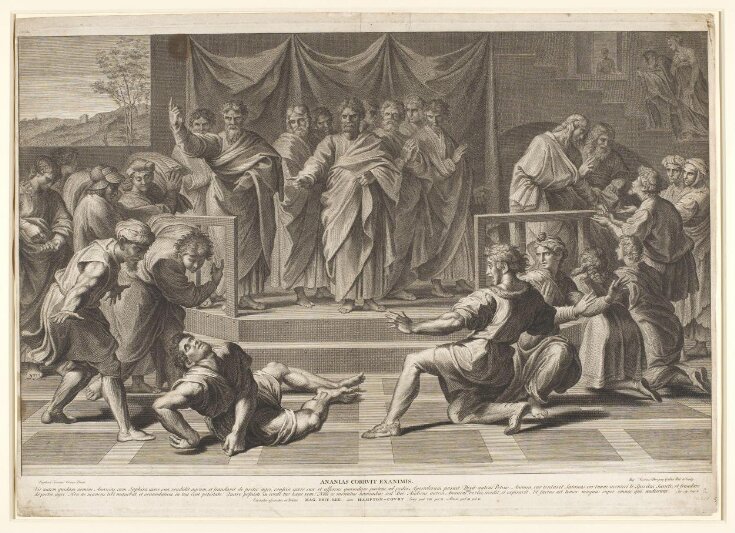

If we define reproduction as ‘to produce a copy of something, or to be copied in a production process’, then the practice of copying works of art predates photography. In fact, it can be extended to manual techniques such as woodcut, engraving, lithography, or painted copies. In a way not too dissimilar to photographic images, for instance, the dissemination of Raphael’s works through prints and painted copies ensured the artist’s fame and posthumous fortune. Translated into image, the original was invariably altered, or interpreted, in these engraved copies. Even though prints evolved from a highly interpretative reproduction to a more faithful and detailed copy, compared to their prototype, they were deemed “untrustworthy” and “even misleading”.2 Especially for a nascent specialist, the connoisseur, who needed to compile a visual catalogue in order to recognise an artist’s style and hand.

The technological reproduction of images, that is, photography, came of age just as art history was becoming an academic discipline, and its impact can be compared to that of the microscope or telescope on science. Art historians quickly took to the new medium for research as well as teaching, and the new medium in turn transformed their approach. While aesthetic judgements previously relied on recollection and imprecise aids such as sketches, photography enabled accurate visual comparisons that were the foundation for a secure, scientific analysis of works of art. Subjective art criticism gave way to methods like connoisseurship, formalism, and iconology.3

The first international congress of art historians convened in Vienna in 1873 was a founding moment for the history of art. In the opening speech, Moriz Thausing (1838-1884) laid the academic foundations for a history of art as a wissenschaftliche (scientifically rigorous) discipline and proclaimed its independence from aesthetics and archaeology.4 On that occasion, a whole session was devoted to discussing the impact of photography on research and teaching. The chair of art history at Leipzig University, Anton Springer (1825-1891) proposed to create a society for the photo reproduction of artworks. Bruno Meyer (1840-1917) from the University of Karlsruhe attempted to demonstrate the teaching potential of lantern slides. Marcy’s Sciopticon had just been commercialised in the 1870s. This magic lantern could project of images on glass and was extensively employed by art historians in Germany and America. But the quality of the images taken from prints and not originals was still rather poor.5

Notwithstanding the great advantages of the new medium, quite soon scholars began debating on its potential negative impact on aesthetic discrimination as well as the dangers of relying on the “all too-plausible photograph as the real thing”.6

The importance of photography in shaping art historical methods is most evident in the work of the Swiss scholar Wölfflin, as brilliantly illustrated by Geraldine Johnson. One of the founding fathers of the history of art, Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945) developed the formalistic approach whereby works of art are considered first and foremost as images rather than objects. Drawing from previous theories of perception, Wölfflin believed that style reflected a shift between two modes of vision, the tactile and the visual, which depended on the psychological apprehension of reality. This was articulated in terms of polarities: linear > painterly; plane > recession; closed form > open form; unity > multiplicity; clarity > complexity. Thus the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, which was the focus of his studies, could be explained in psychological terms as the achievement of a painterly vision where “the various parts of a picture are seen as a unity from the same distance”. Wölfflin’s formalist theories were met with exceptional success in the scholarly world and his books were readily translated. During his longstanding academic career in Basel, Berlin, and Zurich, he taught students in the likes of Panofsky, Hauser, Antal, and Walter Benjamin. To effectively illustrate the contrast between the Renaissance and the Baroque, Wölfflin used dual slide projections in a darkened lecture theatre, a practice that left his students quite stunned.

One could argue that Wölfflin’s method would have been unthinkable without the stylistic comparison made possible by photography. But the Swiss art historian was also acutely aware that photographic reproductions could be deceptive and, for this reason, ought to be analysed with a critical eye. Caution must be exercised in particular with sculptures whose photographic reproduction was more problematic. To the subject Wölfflin devoted three articles that appeared in the leading journal Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst (1896, 1897, 1915).7 If a painting could only be photographed from the point of view intended by the artist, a sculpture could be photographed from unusual or multiple angles in order to achieve a painterly effect that may not be congruent with the sculptor’s vision. This was particularly true for renaissance sculpture whose balance, symmetry, and harmonious composition could only be appreciated from a frontal point of view. By contrast, the asymmetry and painterly qualities of Baroque sculpture allowed for multiple viewpoints. Inaccurate reproduction could not only mislead the uneducated public but also perpetuate false impressions that had repercussions on museum displays, too.

“The problem of photographing the [sculpted] figure overlaps completely with the problem of viewing the [sculpted] figure. It only lets itself be treated historically: there is no universal answer to the question of how figures are to be viewed. Beyond its theoretical importance, the matter has a practical side, insofar as the demand for a determinate view must naturally determine museum installations.”8

Among Wölfflin’s students in Berlin was also a young Walter Benjamin (1892-1940). Although he was not impressed with his teaching abilities – he found him “pedantic” and “ludicrously catatonic”, Wölfflin’s ideas on the distortive nature of photographic reproductions made a lasting impression.9 The obvious reference is Benjamin’s best known and most often (mis)quoted essay, The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility (1936-39).10 According to Benjamin, manual reproductions, such as Marcantonio Raimondi’s engravings after Raphael, did not detract from the authority of the original work of art. The photographic image, on the other hand, lends itself to alteration or manipulation of the original. The lens can reveal aspects that are not detected by the human eye, but equally copies can place the subject in a situation that the original would not attain. Even the best reproductions lack the physical presence that makes the work of art authentic and unique. The work of art is thus demystified, stripped of its aura, detached from tradition and actualised in the viewer’s own situation. The cult value that stems from the initial magical and religious purpose of the work of art and survives in the secularised aesthetic beauty, has been replaced by the exhibition value, which is connected to the accessibility of the art object. With photography, the latter has reached its zenith with art being transformed into a mass experience.11

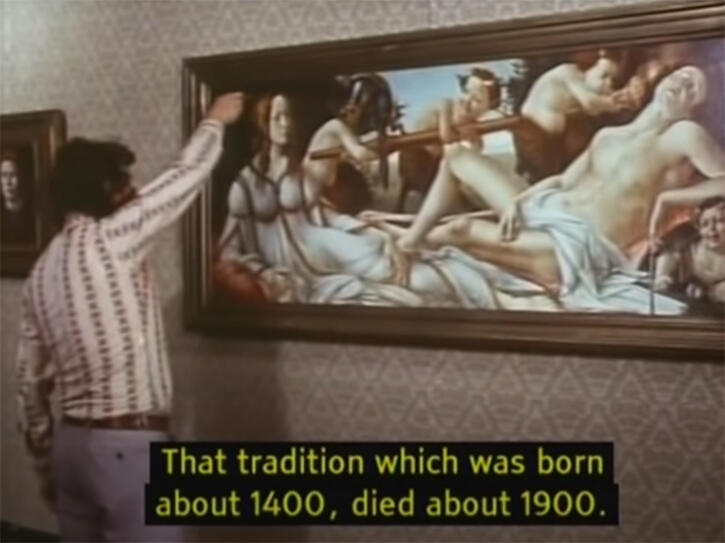

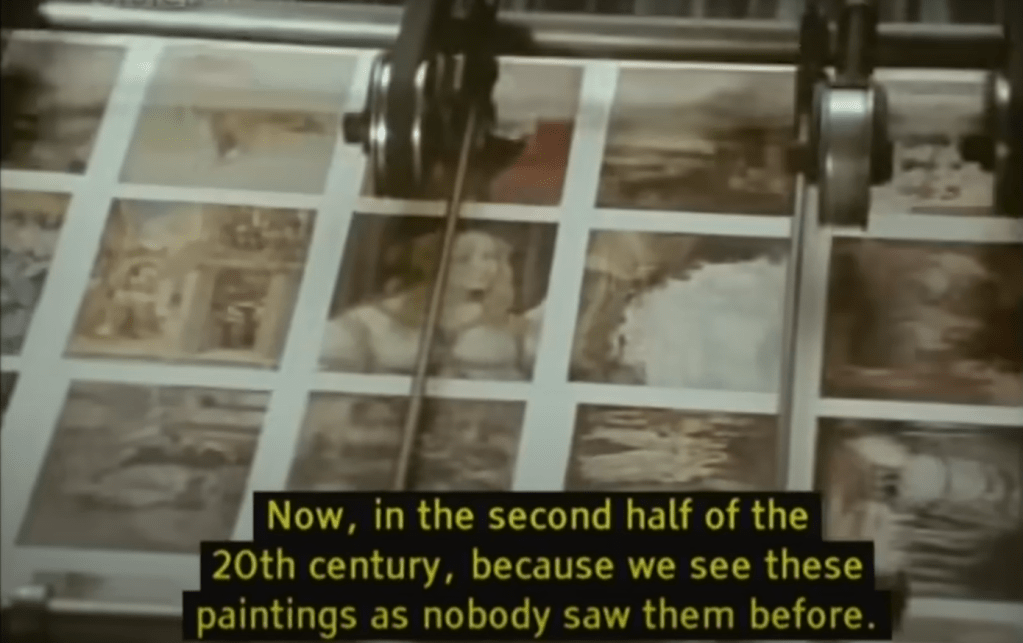

Benjamin’s ideas remained fairly unknown until Adorno edited a collection of his writings in 1955.12 Ripples of the essay on image reproducibility reverberated in another author, Arnold Hauser (1892-1978), whose Social History of Art (1951) provided a summation of Benjamin’s theories. It was not until the late sixties, however, that The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility would appear an English translation as part of the selected essays Illuminations (1968).13 In 1972, Benjamin received a wider popularisation in the BBC2 documentary Ways of Seeing by John Berger (1926-2017). Berger began the now celebrated TV series by cutting into what we later learn to be a reproduction of Botticelli’s Venus and Mars. His aim was to show the decontextualisation and manipulation implicit in photography and cinema. Referencing to Benjamin, Berger proceeded to demonstrate how the invention of photography had altered the perception of art and how mass reproduction had damaged the aura of works of art. Taking Benjamin’s argument further, Berger examined the exploitation of images in advertising, television, and news information at the service of patriarchy and western imperialism.14

The post-war explosion of blockbuster exhibitions may be taken as a perfect illustration of the cult and exhibition values postulated by Benjamin. These commodified mass experiences, often responding to economic and political agendas, had a great public appeal. A standout example was when the popular icon par excellence, the Mona Lisa, was taken on tour to the United States in 1963. At the height of the Cold War, the show was laden with political significance and inspired Pop artist Andy Warhol (1928-1987) to replicate the iconic image over and over on a silkscreen print. The result was a manifestation of Benjamin’s indictment. The multiplied Mona Lisa no longer mattered as a real work, just like Marilyn Monroe or Jackie Kennedy did not matter as real persons. As Hans Belting cleverly observed: “If the Mona Lisa was a mere cypher for art, it was possible to hide the actual work behind the endlessly repeated stereotypes.”15

The Mona Lisa was on that occasion accompanied by the French Minister of Culture, André Malraux (1901-1976). A Marxist novelist and art historian, Malraux wrote a pivotal essay on photo reproduction, Le musée imaginaire (1947) whose expanded version was later included in the book Les voix du silence (1951). According to the French art historian, museums and photo reproductions divested the work of art of its function and its authenticity. Readily available images of works of art, moreover, enabled a “museum without walls”, that is, a revelation of the world art beyond the confines of an art gallery.16 Each museum exhibit was a representation of something differing from the thing itself insofar as its raison d’être changed. The work isolated from its context had become something else, its aesthetic value was now judged against others displayed alongside it. But it was the advent of photography that ultimately brought about a more rigorous art history:

“In the art knowledge of those days [before photography] there was a pale of ambiguity […] due to the fact that the comparison of a picture in the Louvre with another in Madrid was that of a present picture with a memory. Visual memory is far from being infallible, and often weeks had intervened between the inspections of the two canvases. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, pictures, interpreted by engraving, had become engravings; they had kept their drawing but lost their colors, which were replaced by interpretation, their expression in black-and-white; also, while losing their dimensions, they acquired margins. The nineteenth-century photograph was merely a more faithful print, and the art-lover of the time ‘knew’ pictures in the same manner as we now ‘know’ stained-glass windows.”17

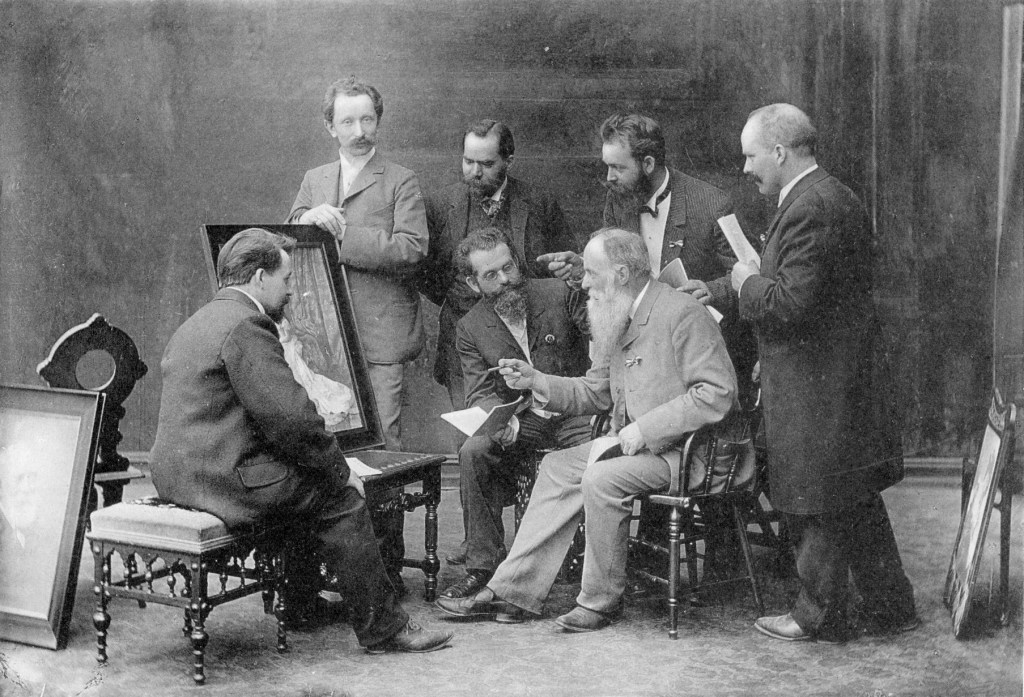

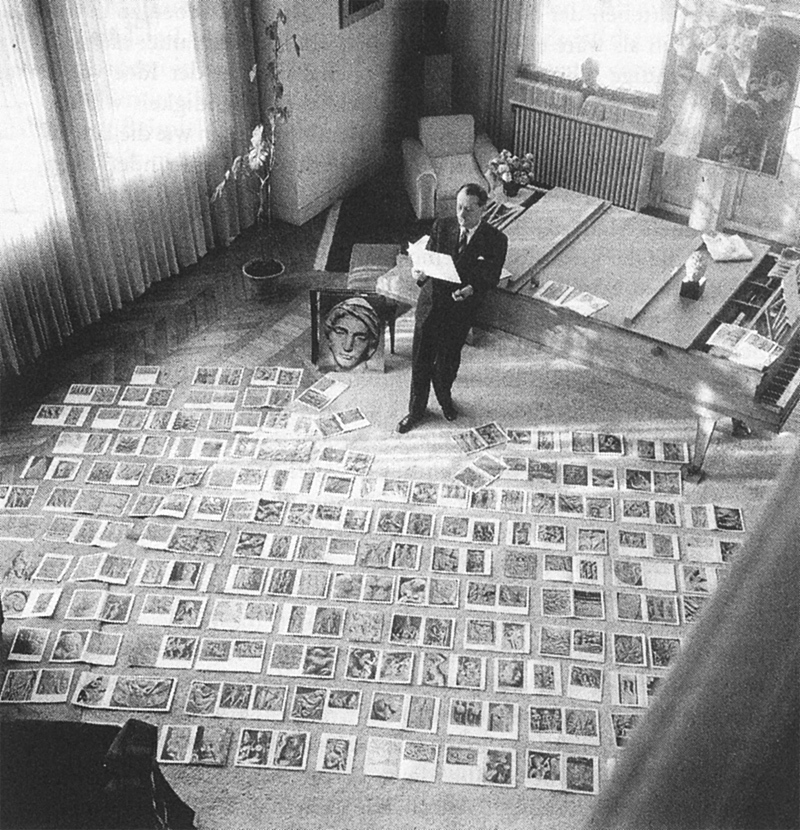

By presenting an anthology, the corpus of an artist or a school, photographic reproductions forged a new hierarchy based on how a masterpiece compares not to its (classical or Italianate) rivals, but on its belonging to a typological family.18 Photographs invariably shifted the focus from the material object to its style. In an illustrated book, the differences in technique or size were obliterated. Lighting and scale can had the power of elevating details or minute fragments to the status of the Elect, changing the outlook on certain art forms. Ancient or tribal sculpture could in this way could be made out to fit a sense of spurious modernism. True to his ideas, Malraux was the subject of an iconic photograph of him selecting pictures for the next book, Le Musée Imaginaire de la Sculpture Mondiale (1952). Quite aptly, this ubiquitous photo came to be identified with the discourse on photo reproductions or, more in general, the art historian’s work.19

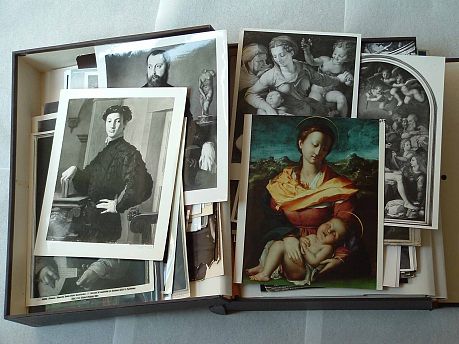

Malraux’s “album” has been compared to another famous photographic “atlas”, the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, a rhizomorphic montage put together by Aby Warburg (1866-1929).20 The Bilderatlas consisted in sixty-three panels with approximately a thousand photos which Warburg began to assemble in 1927. The project subtitle was quite self-explanatory: Image Sequence for the Cultural Study of Expressive Material Reminiscent of Antiquity in the Representation of Cosmic Movements during the European Renaissance. The survival of classical sources and classical tropes in Western art was the focus of Warburg’s life’s work. Using an interdisciplinary approach that encompassed religious, literary, folk and anthropological culture, Warburg endeavoured to chart a visual history of human expression. Just as the arrangement of the books in his library according to the law of good neighbourliness subverted dogmatic disciplinary boundaries and hierarchies, the juxtaposition of images served to reveal unexpected intercultural connections. Comprising reproductions of works of art in their complete form, blown-up details, postcards, sketches, and newspaper cuttings, the Atlas was crucial in Warburg’s intellectual process and practice. Mnemosyne was conceived as a work-in-progress. Warburg continuously reorganised the panels around the constellation of themes in his protean research on the migration of forms. 21

Benjamin had more than a passing interest for Warburg’s work.22 Although the two never met, many aspects investigated by the Hamburgh cultural historian intersected Benjamin’s own research, such as the historicity of experience, the relationship between modernity and social memory, the collective memory deposited in works of art, and the connection between history and images.23 As a matter of fact, after his Habilitation, Benjamin did seek to join Warburg’s circle but with little success. Commentators have emphasised the great epistemological influence of Mnemosyne on Benjamin’s contemporary Passagen-Werk (or Arcades Project).24 Warburg had already passed away when Benjamin published his essay on technological reproducibility, though admittedly it was not the scholarly usage of images but their mass fruition that was the target of his criticism. As it happens, Benjamin later delved into photographic montage and Surrealism.25

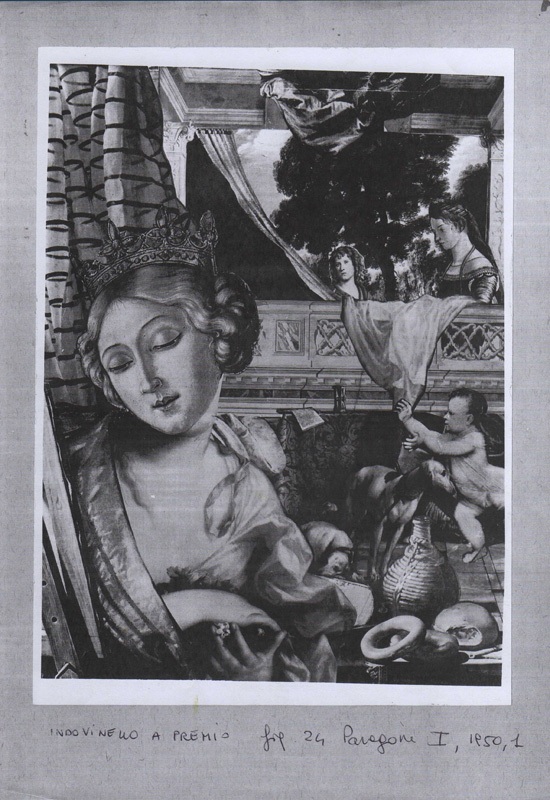

In the hands of art historians, image manipulation could be even employed as an educational tool to test the connoisseur’s eye. This was the intention of an art historian and attributionist extraordinaire like Roberto Longhi (1890-1970), who amused the readers of the first issue of Paragone Arte (1950) with a visual indovinello a premio (i.e., riddle with a prize). Basking in the laurels of connoisseurship was the reward for those who managed to recognise the details from different paintings pasted together in a clever collage by Giulio Briganti. Divertissement aside, attribution was a serious business and photographs were a crucial research and teaching aid. The extensive photo archives left by connoisseurs like Roberto Longhi, Bernard Berenson and Federico Zeri, to name but a few examples, are there to prove it. But in today’s highly digitised world, these photographic collections have almost ceased to be consulted as repositories and have become an object of study in themselves. Just like an art collection sheds light on the collector’s taste, image collections document the art historian’s thought process, research interests, and (un)finished projects. Should they contain handwritten notes on provenance or presumed authorship, these photographic reproductions attain the status of originals whose ‘cult value’ enthrals the present-day art historiographer.

Photography may have foregrounded the commodification of art as Benjamin predicted, but one must also recognise that without reproductions there would not be art history. To use Malraux’s words, “art history has been the history of that which can be photographed.”26

- In a recent survey book on modern painting, for instance, the author warned: “While the Internet allows easy and free access to an unprecedented number of images of paintings, […] we should always remember that a photograph of a painting is just that, a small-scale, flat, synthetically coloured, digitally generated reproduction. […] Real paintings, by contrast, are meant to be experienced in three-dimensional environments […] where we are open to more embodied, sensual forms of experience and knowledge”, in S. Morley, Modern Painting. A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson, 2023), pp. 8-9. ↩︎

- B. Berenson (1893), quoted in G.A. Johnson, ‘”(Un)richtige Aufnahme”: Renaissance Sculpture and the Visual Historiography of Art History’, in Art History 36 (2013), 1, pp. 12-51: 32. ↩︎

- A. Venturi, ‘Prefazione’, in Ad Braun et C.ie. Catalogue general des Photographies… (1887), translated in ibid., p. 32. ↩︎

- M. Thausing, ‘The status of the history of art as an academic discipline’, transl. by K. Johns, in Journal of Art Historiography 1 (2009), pp. 5-13. ↩︎

- M. Männig, ‘Bruno Meyer and the Invention of Art Historical Slide Projection’, in Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives (Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, 2019), https://www.mprl-series.mpg.de/studies/12/17/index.html. ↩︎

- T. Fawcett, ‘Graphic versus Photographic in the Nineteenth-Century Reproduction’, in Art History 2 (1986), pp. 185-212: 207. ↩︎

- Wölfflin’s articles were translated into French, Italian, and now also made available in English: H. Wölfflin, ‘How One Should Photograph Sculptures’, in Art History 36 (2013), 1, pp. 52-71. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 61. ↩︎

- Cf. T.Y. Levin, ‘Walter Benjamin and the Theory of Art History’, in October 47 (1988), pp. 77-83. ↩︎

- Benjamin first expressed his ideas on the emancipation of the object from the aura in an essay on Eugène Atget, see ‘A Small History of Photography’ (1931), in One Way Street and Other Writings (London: NLB Verso, 1979), pp. 240-57. ↩︎

- W. Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility’ (1935-36), in M.W. Jennings, B. Doherty and T.Y. Levin (eds.), The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2008), 19-55. ↩︎

- Cf. T. Lijster, Benjamin and Adorno on Art and Art Criticism (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017). ↩︎

- W. Benjamin, Illuminations. Essays and Reflections, with an introduction by H. Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968). ↩︎

- J. Berger, ‘Chapter One,’ Ways of Seeing (BBC & Penguin, 1972), 7-34 + Episode One (shown in 4 parts) on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LnfB-pUm3eI ↩︎

- H. Belting, The Invisible Masterpiece (London: Reaktion Books, 2001), p. 292. ↩︎

- A. Malraux, The Voices of Silence (St Albans: Paladin, 1953). ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 16. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 21. ↩︎

- Cf. W. Grasskamp, The Book on the Floor. André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2016). ↩︎

- G. Didi-Huberman, ‘ALBUM vs. ATLAS (Malraux vs. Warburg)’, in A. Kramer and A. Pelz (eds.), Album (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2013), pp. 59-73. ↩︎

- Cf. M. Kalkstein, ‘Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas: On Photography, Archives, and the Afterlife of Images’, in Rutgers Art Review: The Journal of Graduate Research in Art History 35 (2019), pp. 50-73. ↩︎

- M. Rampley, Benjamin’s Warburg: On the Influence of Walter Benjamin on Aby Warburg, London, Warburg Institute, 14 June 2012. ↩︎

- Cf. M. Sergio, ‘Aby Warburg, Walter Benjamin, and the Memory of Images’, in Engramma 191 (2022). ↩︎

- Benjamin began the unfinished Passages in the same year as Mnemosyne, 1927, and he, too, worked on the project until his death. ↩︎

- Cf. G. Didi-Huberman, Atlas: How to Carry the World on One’s Back? (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2010); id., Atlas, or the Anxious Gay Science (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018). ↩︎

- Malraux, The Voices of Silence, cit., p. 30. ↩︎

Leave a comment