Stories of brass abstractions and undead knights

The earliest forms of artistic expression were to commemorate the dead and propitiate good fortune. Memorialisation, in particular, played a very important part in artistic development for insofar as it implied a likeness of the departed that was contingent on religious or spiritual beliefs as much as on social conventions. While death is indeed a private moment, memorial effigies are a public affair whose purpose was to engage the living in aid of the dead and celebrate social status in perpetuity.

The anthropological and cultural implications of tomb sculpture are a topic that has fascinated many scholars. From an artistic perspective, Erwin Panofsky (1892-1968) studied at length the iconology of funereal effigies from antiquity to the Baroque, condensing years of research into a series of lectures published in 1964.1 The rituals and modes of representation of death were later comprehensively examined by Paul Binski in an important survey on Medieval Death (1996).2 Other important works dealing with more specifically English commemorative relief sculpture and brasses include Laurence Stone’s Sculpture in Britain: The Middle Ages (1955) and Malcolm Norris’s Monumental Brasses: The Memorials and The Craft (1977-78).3 Another essential reference is the 2009 survey book English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages, in which Nigel Saul analysed the design, geography, style, meaning and material aspects of commemorative sculpture.4

The rebirth of effigial monuments in the 12th century marked a significant turning point in English tomb sculpture. While classical models survived on the Continent in the early Middle Ages, commemorative monuments were dominated by non-figural designs in Anglo-Saxon England. Funerary sculpture subsequently flourished in a mixture of both indigenous and continental forms. This development was particularly evident in two prominent English commemorative types, monumental brasses and the dying knight.5

Brass rubbing

In Britain, the large concentration of commemorative plates ranging between the 13th and the 16th centuries led to the widespread enthusiasm for brass rubbing. The practice of transferring monumental brasses onto paper was a popular Victorian pastime that saw a revival in the mid 20th century.

Monumental brasses evolved from monumental tombs as their two-dimensional planimetric projections that posed no “traffic problem”. As such, these “linear or graphic abstractions” proved extremely advantageous.6 By the 13th century, decorating tomb slabs with enamel components and hard brass had become quite common across Rhineland, France, the Low Countries and England. Soon brasses became the preferred form of tomb memorial as a space-saving, more practical option compared to three-dimensional effigies.7 Moreover, not unlike gold, brass symbolised the idea of ever-lasting untarnishable memory. Being a metal, however, it was often the target of spoliation, a factor that greatly contributed to their disappearance.

Today, brasses can be mostly found in English churches and predominantly in East Anglia. Because of the close ties between the Low Countries and the East of England, the concentration of brasses in this area probably indicates that they were originally a Dutch import. Since the 11th century, the Low Countries traded with the Eastern countries mainly in relation to the wool business. Following the Reformation, many Calvinists fled to England to escape persecution, especially after the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566. The eastern commercial centre of Norwich seized this opportunity to revive its textile industry and welcomed Dutch masters and their families to settle in the city. By 1568, the community of ‘Strangers’ had considerably expanded and their weaving knowledge and skills re-energised the local trade.

Brass memorials were first manufactured in England around 1310 in centres like London. By the 15th century, brasses were the prevalent form of commemoration for the lesser gentry and burgesses. The demand prompted the surge of metropolitan workshops, as can be seen in Norwich around the 1450s, as well as in Cambridge, Bury St Edmunds, Boston, Coventry and Durham.8

While Flemish examples were usually engraved on large plates with a central figure against a decorated background, English brasses featured silhouetted figures with the stone serving as a background. Until 1400, brasses predominantly depicted crosses or inscriptions. Even when they began to include effigies, they always offered a standardised image rather than a true likeness. Albeit idealised, effigies point to a renewed sense of selfhood that was expressed in a complex interplay of image and text. Attributes, such as heraldry, and attire clearly marked the social station of the deceased, whether a knight, a clergyman, or a civilian. Material was another indicator, for instance, bronze was reserved to bishops and sovereigns. What these effigies aimed to represent was indeed not individual identity but the collective idea of belonging to a group.9 The permanent bonds of blood, affinity and alliance in fact mattered much more than what portraiture could achieve.

Panofsky identified different ways of representing the dead that were dictated not only by religious beliefs, but also depending on whether the physical placement of the tomb could be adapted to the artistic conception, or vice versa. Alternatively, the whole issue was sidestepped by replacing the tomb with an epitaph catering for a wider range of subjects. Horizontal placement meant that the effigy would be gisant, that is, lying horizontally. In Northern Europe, the departed tended to be depicted with their eyes open and their hands in prayer. When it came to representing death, two types were possible: the representacion au vif, that is, the dignified depiction of a body unaffected by decay, or the transi, that is, the representation of a dead body covered by a shroud or reduced to a skeleton. An ambiguity between horizontal placement and verticality characterised these monuments: lying figures were conceived as standing, yet footrests and cushions suggested otherwise.10

The studies devoted to the rituals and representation of death in Western cultures have primarily focused on carved or high relief sculptures. Some considerations on sepulchral images, however, also apply to memorial brasses. The 15th-century poem A Disputation Between the Body and the Worms (British Library Additional MS 37049, ca. 1460-70) is a valuable point of departure. The anonymous poet related the experience of seeing a woman’s figure on a tomb whose beautiful and elegant effigy was perceived as a stark contrast with the decaying corpse. Transi tombs, that is, double-decker monuments where the deceased was depicted au vif and as a cadaver, perfectly encapsulated the juxtaposition of a simulacrum eternally untouched by time and the impermanence of a decaying corpse. The intended meaning was clearly a reflection on the transience of life or memento morii.

The 16th-century monument of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany in St Denis is a fine example of a double-decker tomb. The royal couple is portrayed kneeling in prayer, and below as two gaunt, rotting cadavers.

Tomb of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany, 1515-31, Paris, Saint-Denis Basilica

Not unlike all forms of funereal images, the main purpose of brass effigies was to ensure salvation. The departed was normally identified in inscriptions while scrolls contained prayers or other laudatory inscriptions commemorating their deeds. The emphasis, however, remained on the prospective afterlife rather than on the glorification of the past.

In the magnificent St Peter and Paul’s Church in Salle (Norfolk), the brass commemorating Geoffrey († 1440) and Alice Boleyn was placed in the middle of the central aisle. The position signals Geoffrey’s important role as a contributor to the church.11 The family later moved to Blickling and their social ascent peaked a few generations later with their great-grand-daughter Anne marrying King Henry VIII. Geoffrey and Alice were depicted as lying, still bodies with their hands clasped in prayer and eyes open. Their effigies are types rather than portraits, though a little more detail was put into the clothes (especially Geoffrey’s) in connection with their social status.

Another brass commemorates the patron who erected the North transept of the church, Thomas Roose († 1441), and his wife Katherine, together with their sons and daughters beside them. The figures stand on an ornate bracket with their emblem, a rose, that was once part of a more elaborate canopy. The rose interlaced with the letter T was repeated in the ceiling above the brass. Not uncommon was the way of representing children as mini-me replicas of their parents (see for instance, the tomb of Roger Felthorpe and family in Blickling). Progeny not only underscored the role of paterfamilias but also bloodline continuity. Not least, as a result of high infant mortality, offspring was regarded as a precious commodity to be displayed.

Wealthy landowners, knights, and clergymen were memorialised in more ornate brasses. Knightly effigies, in particular, became common from the second or third decade of the 13th century and “survived long after knighthood itself was drained of military reality”.12 The detail and craftsmanship in representing the armour followed the changes that occurred in attire between the 13th and the 16th centuries: from a simple chainmail hawberk to the bacinet (a pointed helmet) to the full plated encasement.13 The standardised models, however, were not always updated to the more contemporary forms and lacked in variety. The same could not be said of continental monuments. The heyday of knightly effigies in England coincided with the military triumphs of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453).14 Chivalry became more deeply intertwined with religious liturgy especially after the inception of the Order of the Garter (1348). The proud display of its insignia in funerary monuments expressed a collective identity founded on individual honour and Christian responsibilities.

St Margaret’s Church in Felbrigg (Norfolk) holds a characteristic example of a monumental brass fit for a member of the aristocracy. Lord Simon de Felbrigge († 1442/3) and Lady Margaret of Teschen († 1416) are represented gisant, hands in prayer and eyes open, inscribed in a Gothic canopy emblazoned with their coat of arms. Lord Simon was depicted in a full plate armour as a Knight of the Order of the Garter complete with St George’s Cross and the garter on the left leg below the knee (bearing the motto “Honi soit qui mal y pense”). The knight is holding a pennon with Richard II’s insignia and his feet rest on a lion symbolising strength. Margaret is fashionably clothed with a long mantle and her hair worn in side buns, while the dog at her feet typically alludes to conjugal fidelity. Lord Simon commissioned the monument when he was still alive and personally saw to the iconographic programme. Contrary to his wish to be buries next to Margaret, he was laid to rest next to his second wife, Katharina, in St Andrew’s Hall in Norwich.

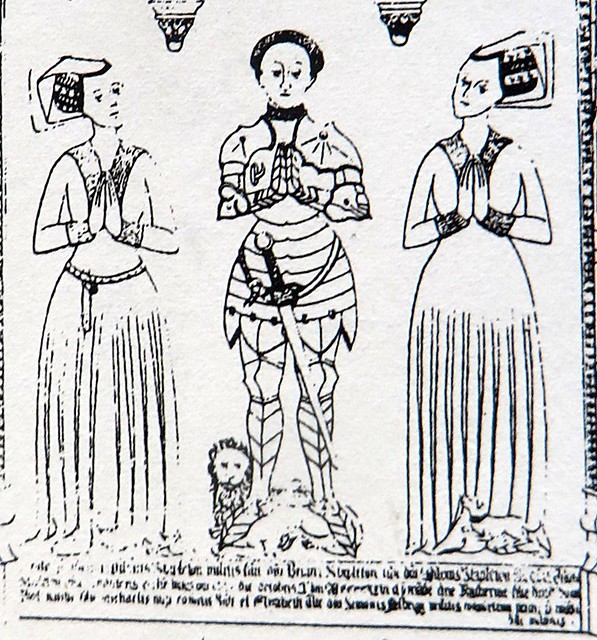

In Ingham, the founder of the Trinitarian Friary, Sir Miles Stapleton († 1466) chose instead to be buried next to his two wives who were represented in the brass as two identical twins with few distinguishing details (the dog’s position and the belt). Unlike in the previous examples, Sir Miles’s wives show their devotion by turning towards their husband. Celebrating marital bonds often reinforced ideas of ancestry or encastlement of the family and kinship.

In a study on mediaeval tomb sculpture, Jessica Barker observed that public and private spheres conflated in conjugal effigies leaving room for both romantic feelings and social institutions.15 In what was a rather typical iconography, Sheriff and Mayor Robert Rugge († 1558) is shown in conversation with his wife Elizabeth at St John’s Maddermarket in Norwich. Instead of professing their endless love, their utterances are much more formal as the scrolls contain prayers for their salvation (“pater de celis deus miserere nobis” and “fili redemptor mundi deus miserere nobis”).

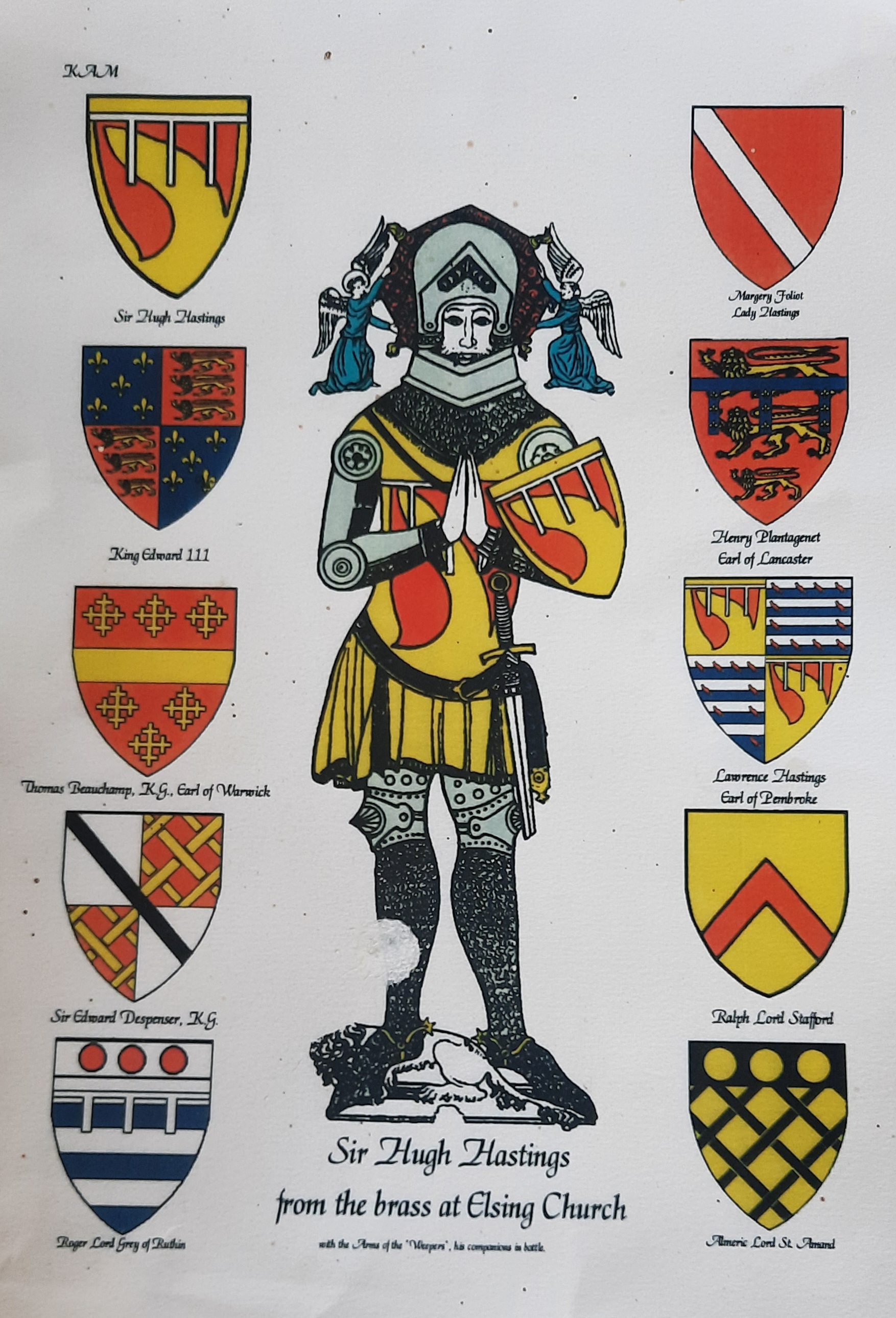

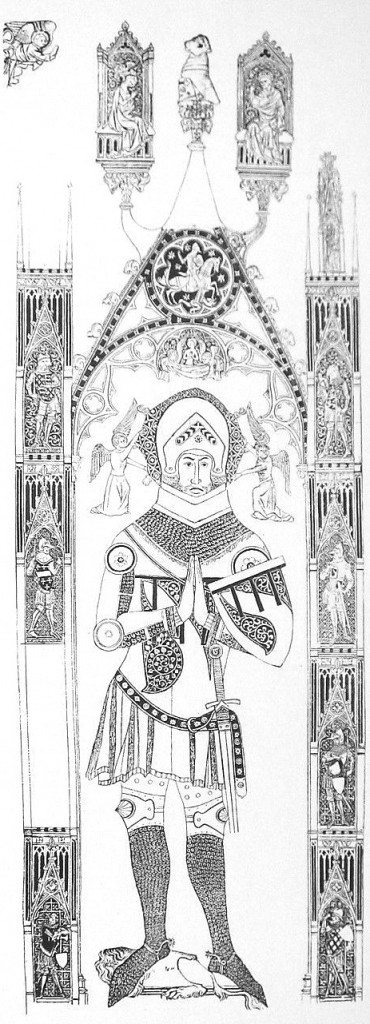

Sir Hugh Hastings, monumental brass, Elsing, Parish Church of Saint Mary the Virgin

The brass of Sir Hugh Hastings († 1347) in St Mary’s Church in Elsing (Norfolk) is arguably one of the finest memorials to a layman, unparalleled in its richness.16 Sir Hugh is shown wearing a suit of armour emblazoned with the Hastings coat of arms. Above him is a canopy supported by weepers on each side. The central oculus bears the image of St George which, together with the Coronation of the Virgin in the tabernacles, signals his belonging to the Order of the Garter.17 Sir Hastings was a Captain and Lieutenant in Flanders and had fought alongside King Edward III in the Battle of Crécy (1346) at the beginning of the Hundred Years War. He died a year later, in 1437, during a riot in Boston (Lincolnshire). His distinguished military career and social standing were celebrated in this exquisite brass that was originally gilded and embellished by enamels and coloured glass. The complex iconographical programme was meant to convey a twofold message: “the triumph of the Christian faith over death and the triumph of the English in arms over the French”.18

Sir Hugh is in full armour, hands clasped in prayer, his feet on a lion footstool emphasising his bravery in combat. His head rests on a cushion supported by angels and above him two panels show the Coronation of the Virgin and Christ in Majesty. His soul is being carried away by angels and above them is a roundel with St George slaying the devil. The shafts consist of panels with a series of mourners, his companions in arms, led by King Edward III. The brothers who had fought with Hastings in France included Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick; Henry of Grosmont; Sir John Grey of Ruthin; Henry Plantagenet, Earl of Lancaster; Laurence Hastings, Earl of Pembroke; Ralph de Stafford, Lord Stafford; and Sir Aymer St Amand.

Weepers or pleurants became a fixture in tomb iconography in the 13th century inspired by French examples (such as the tomb of Louis of France at Royaumont Abbey).19 These standing figures formed a cortege normally located at the foot of the tomb either as freestanding pieces or in niches, as can be seen in Richard Beauchamp’s effigy in the Collegiate Church of St Mary in Warwick. Unlike the continental counterpart, in England weepers are not grieving but alert and sociable. Instead of recreating the funeral procession, they encouraged intercession on their behalf.

Later reconstructions of Sir Hastings’s brass were based on the detailed description provided for the Court of Chivalry hearing convened in Elsing in 1408. The preoccupation with group identity and lineage that inspired the iconographical programme of Sir Hastings’s tomb proved extremely useful as the brass was cited as evidence to establish the right to bear the arms of the Hastings.

The dying Gaul who cheated death

LEFT: The Dying Gaul, or The Capitoline Gaul, a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic work of the late 3rd century BCE Capitoline Museums, Rome; After Epigonus of Pergamum, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. RIGHT: Effigy of a medieval knight – St Peter’s church, Dorchester by Mike Searle, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Free-standing tomb chests with effigies became the preferred choice amongst the landed gentry from the 14th century.20 Three-dimensional relief sculpture was produced in London workshops especially for elite customers, while provincial centres began to emerge in the mid 15th century. A particular type that developed in Britain for knights was the so-called Dying Gaul in reference to the famous Roman marble. Defying the notion of eternal sleep, the knight assumes a cross-legged pose and is poised to draw his sword. Crossed legs were considered a sign of aristocratic nonchalance, but in this case they refer to readiness for action. A typical example is the Sword-drawing Knight, also known as Dancing Knight, in Dorchester Abbey (mid-13th century). This position distinguished the warrior who had perished in battle and, originally, it was thought to be a distinction reserved to crusaders who had died for their faith.

Another variation can be found in East Anglia in the 14th-century tombs of knights in Ingham, Reepham and Borrough Green. These relief effigies were carved from Purbeck marble, a limestone native to Dorset quarried since the Roman times which was largely employed for its polished finish.21 The armoured figure lying on a bed of cobbles alludes to hardiness as well as penance. Paul Binski interestingly linked the development of this iconography to the contemporary Arthurian legends about valiant knights and courtly romance.22

Sir Oliver de Ingham, tomb chest, Ingham, Church of the Holy Trinity

The tomb of Sir Oliver de Ingham († 1343) in the Church of the Holy Trinity at Ingham, though overall less preserved, sheds further light on the lifelike effect of dying knights. This tomb was possibly designed by the royal master mason William de Ramsey († 1349), in itself a telling sign of the patron’s social status.23 Based on the traces of polychromy and evidence mentioned in an old manuscript, it was possible to visually reconstruct how the tomb looked in the 14th century. The body of Sir Oliver is turned to admire the painted scene from the life of St Giles that once adorned the recess behind him. The colours used were those of Sir Oliver’s coat of arms, while the hunting scene was conjured up in a 1589 manuscript: “he being a great traveller lyeth upon a rock, beholding the sun and moon and stars all very lively set forth in metal”. When the tomb was opened, a suit of armour was found inside, which was later stolen. At the base of the sarcophagus is a theory of weepers praying for the salvation of Sir Oliver’s soul.

Sir Roger de Bois and Margaret, tomb chest, Ingham, Church of the Holy Trinity

In the same church, another tomb chest bears the effigies of Sir Roger de Bois († 1300) and wife Margaret († 1315), which was also colourfully painted and richly decorated. The chest is surrounded by the customary procession of mourners and one side is decorated by a panel with the Holy Trinity.

Sir Roger de Kerdeston, tomb chest, Reepham, St Mary’s Church

Arguably one of the best preserved dying knights is the cross-legged effigy of Sir Roger de Kerdeston († 1337) in Reepham (Norfolk).24 Set on the north side of the aisle, this monumental canopied tomb closely resembles the one in Ingham. This sculpted chest, too, was originally painted and adorned with a hunting scene in the background. The base also features an almost complete series of mourners.

Often considered an allusion to self-mortification, the undead knight refusing to surrender until his dying breath epitomised the miles Christi or guardian of faith.

A taste for the macabre

The appetite for gruesome realism in transi monuments has been often linked to the morbid obsession with death of the mediaeval mind. Yet, cadaver tombs peaked as a phenomenon in the early 16th century, and even then, they were a rare occurrence.

The shocking sight of putrefying cadaver was intended to remind the onlooker of the inevitability of death and visually engage with their conscience. Patrons commissioned these macabre monuments to convey their repentance and atonement, acting as a mirror of their own mortality.

LEFT: L’homme à moulons, 16th century, tomb effigy, Boussu, Chapel; NOELRoger, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. RIGHT: François de Sarrà, c. 1400, tomb effigy, La Sarraz, Château.

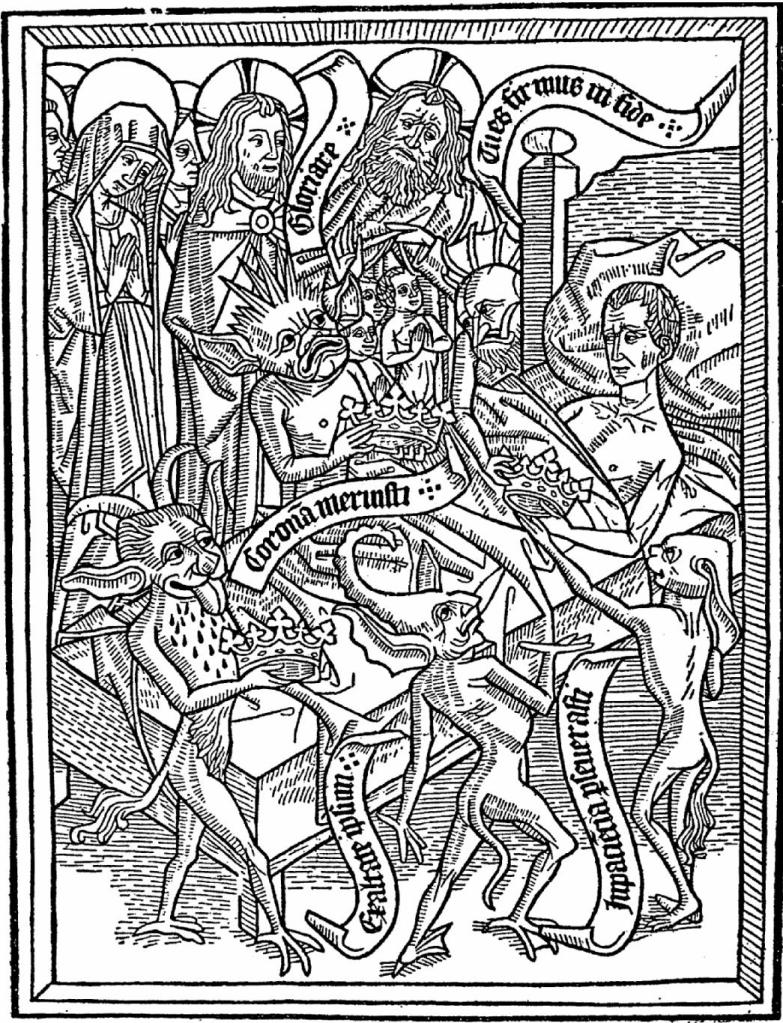

In England, double-decker monuments were not as popular as shroud brasses, that is, brass effigies in which the commemorated are shown either naked or as skeletons wrapped in burial shrouds. Both cadaver tombs and shroud brasses derived from continental models as their geographical distribution indicates. Their high concentration in Norfolk can be again put down to the Flemish connection of the eastern county. The demand for this type of brasses was serviced by Norwich workshops with designs modelled on grisly iconographies taken from Flemish woodcut images depicting subjects like the Three Living and Three Dead and the Dance of Death.

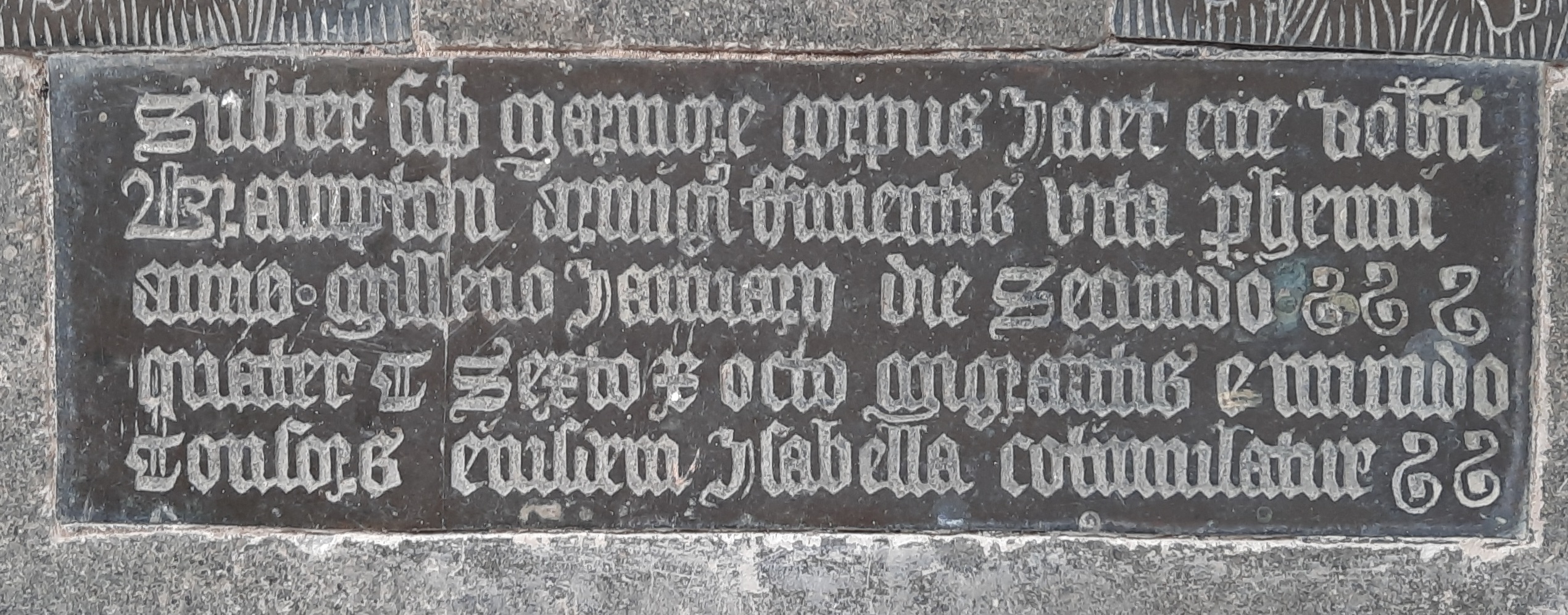

Robert and Isabella Brampton, c. 1483, brass, Brampton, St Peter’s Church

In the commemorative brass at Brampton, Robert Brampton († 1468) and his wife Isabella are shown enveloped in their burial shrouds, their eyes wide open, their gaze turned upwards in adoration of the apparition of the Virgin and Child above them. Their words recorded in the scrolls – “Magnificent Mother, have mercy on me Mary in my misery” and “Virgin, worthy of God, look benignly on those who pray” – convey the positive message of bodily resurrection and salvation through Christ.

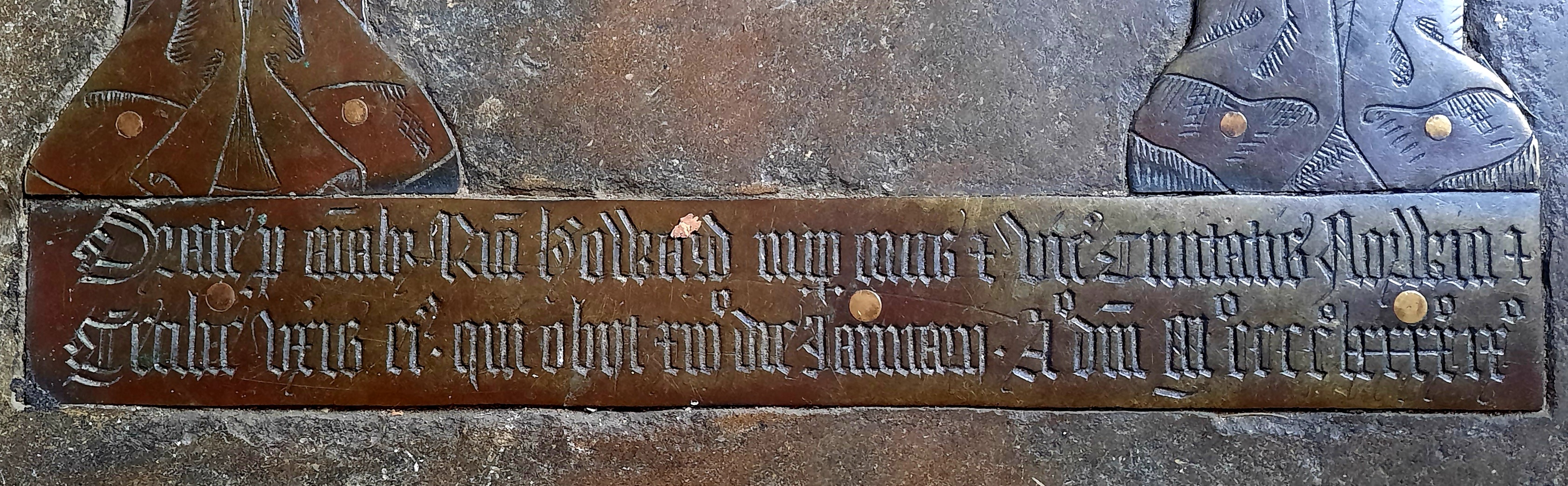

Richard and Cecily Howard, brass, Aylsham, St Michael and All Angels Church

A few miles from Brampton, in the once prosperous cloth-making town of Aylsham, the church of St Michael and All Angels boasts an exquisite skeleton brass of Richard Howard († 1499), baker and sheriff of Norwich in 1488, and his wife Cecily. Richard Howard and his third wife are represented as skeletons wrapped in winding sheets. The inscription below the effigies reads: “Pray for the souls of Richard Howard, late a citizen and sheriff of the city of Norwich, who died on the 13th day of January in the year of our Lord 1499, and his wife Cecily”. Upon close examination, Julian Luxford convincingly argued that contemporaries would have interpreted the apparently macabre theme as a “statement of optimism about death”.25 The liveliness and contentment of the Howard skeletons would have been seen as an allusion to the resurrected body and soul cleansed at last of purgatorial contrition. The lesson to be drawn by the beholder was the value of a wholesome and moral life. In turn, the onlooker would have felt compelled to pray for the salvation of the deceased. By comparison to funeral liturgy, these skeletons would have been seen as an illustration of salvation attained after death and decay – hence the Howards’ full-toothed grins.By referring to funeral liturgy, moreover, this image would have been seen as an illustration of death and decay as necessary stages in the path towards salvation (hence the Howards’ full-toothed grins!).26

Why tomb sculpture?

The proliferation of tomb sculpture can be explained with the need to draw attention to one’s wealth and social standing. Another reason must be found in a significant theological introduction that strengthened the bond between the living and the dead. In 1274, the Church formally recognised Purgatory.27 The desire to ease one’s way through purgatorial redemption motivated most pious provisions in pre-Reformation England.

According to this new doctrine, purgatorial suffering could be remitted through the actions performed in life as well as through the assistance of others after death. Sizeable donations and regular funerary services provided for in wills became a common way to ease one’s way through purgatorial redemption. More emphasis was placed on iconographies like Christ in Judgement with the Virgin Mary and St John acting as intermediaries, and St Michael weighing souls. In a similar vein, funerary monuments were designed to remind the living to pray for the souls of dead. In simplistic terms, the more elaborate the effigy, the more prominent its placement and proximity to the high altar, the more remarkable the deeds committed to memory, the more worthy the deceased was to be saved. As compellingly put by Jacques Le Goff:

“The system of solidarity between the living and the dead instituted an unending circular flow, a full circuit of reciprocity. The two extremes were knit together.”28

In resonance with this mutual dependence, the religious building came to be viewed as a machine for commemoration or a theatre of memory.29

The aftermath of the Black Death fuelled what was deemed an obsession with or fear of mortality that took root in collective mentality. A century ago, Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) attempted to explain this taste for the macabre:

“A thought which so strongly attaches to the earthly side of death can hardly be called truly pious. It would rather seem a kind of spasmodic reaction against an excessive sensuality. In exhibiting the horrors awaiting all human beauty […] these preachers of contempt for the world express, indeed, a very materialistic sentiment, namely, that all beauty and all happiness are worthless because they are bound to end soon.”30

A key to understanding how contemporaries visualised death can be found in the 15th-century treatise Ars Moriendi (1415-50). Popularised in widely circulating illustrated printed editions, The Art of Dying outlined what to expect during one’s last moments, the agony of temptations to resist, the comfort to take in salvation, the appropriate behaviour at the deathbed, and the prayers that should be said on behalf of the deceased. Huizinga believed that the cruder vision of death left no room for tenderness and consolation. In their place, a self-seeking and earthly sentiment prevailed:

“It is hardly the absence of the departed dear ones that is deplored; it is the fear of one’s own death, and this only seen as the worst of all evils. […] The dominant thought […] hardly knew anything with regard to death but these two extremes: lamentation about the briefness of all earthly glory, and jubilation over the salvation of the soul. All that lay between – pity, resignation, longing, consolation – remained unexpressed […]. Living emotion stiffens amid the abused imagery of skeleton and worms.”31

Like a pendulum between extremes, tomb sculpture tapped into contrasting attitudes and states of mind. Undying knights and their followers, faithful spouses with four-legged companions, or rotting corpses, all these effigies reflect on the same themes: vanitas, memento mori, contemptus mundi, and commemoratio.

- E. Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture: Four Lectures on Its Changing Aspects from Ancient Egypt to Bernini, ed. by H.W. Janson (New York: Harry N. Adams, 1964). To mark its 50th anniversary, Panofsky’s seminal book was critically reconsidered in a recent publication: A. Adams and J. Barker (eds.), Revisiting the Monument: Fifty Years Since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture (London: The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2016). ↩︎

- P. Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1996). ↩︎

- L. Stone, Sculpture in Britain: The Middle Ages (Harmondsworth: Yale University Press, 1955); M.W. Norris, Monumental Brasses: The Memorials (London: Faber & Faber, 1977) and Monumental Brasses: The Rituals (London: Faber & Faber, 1978). ↩︎

- N. Saul, English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages: History and Representation (Oxford: OUP, 2009). ↩︎

- For an overview on the history of funerary art in England, refer to Saul, English Church Monuments cit., esp. chapter 2. ↩︎

- Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture cit., p. 53. ↩︎

- Binski, Medieval Death cit., p. 92: “The brass, which now insinuated itself into every aisle and nook of the medieval church very often at the specific request of its subject’s will, was rather an economical and irreproachable solution to the politics of space and display which had arisen with mass burial in church.” ↩︎

- S. Badham, ‘London Standardisation and Provincial Idiosyncrasy: The Organisation and Working Practices of Brass‐Engraving Workshops in pre‐Reformation England’, CM 5 (1990), pp. 3-25. For a detailed analysis of the production and distribution of brasses in Norfolk also refer to J. Finch, Church Monuments in Norfolk before 1850. An Archaeology of Commemoration (London: British Art Series, 2000), esp. pp. 37-44. ↩︎

- Binski, Medieval Death cit., pp. 102-3: “There seems to be no special reason why a tomb likeness should have been seen as aiding the salvation of this particular person. […] Portraiture in this regard was functionally superfluous.” ↩︎

- Saul, English Church Monuments cit., chapter 7. ↩︎

- Geoffrey was charged with stealing timber from the crown’s lands for the church. ↩︎

- Saul, English Church Monuments cit., chapter 9. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid.: “Edward III’s massive victories over the French generated an outburst of chivalric pride which found expression in heraldic self‐consciousness. After four decades of setback and defeat for English arms, the tide of military fortune had finally turned. The king’s victories enabled the nobility and gentry to regain a sense of confidence in their vocation.” ↩︎

- J. Barker, Stone Fidelity. Marriage and Emotion in Medieval Tomb Sculpture (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2020), esp. p. 7: “the personal must be balanced against the structures of social discourse and conventions of representation; the growing popularity of memorials to married couples needs to be situated within a landscape of new ideas in the closing centuries of the Middle Ages.” ↩︎

- Stone described it as the most accomplished brass in England, Stone, Sculpture in Britain cit., pp. 164-7. ↩︎

- Cf. Norris, Monumental Brasses cit., I, pp. 18–19; J. Finch, Church Monuments in Norfolk before 1850. An Archaeology of Commemoration (London: British Art Series, 2000), p. 28; J. Luxford, ‘The Hastings Brass at Elsing: A Contextual Analysis’, in Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society 18 (2011), 3, pp. 193-211. ↩︎

- Saul, English Church Monuments cit. ↩︎

- Cf. S. Jugie, The Mourners. Tomb Sculpture from the Court of Burgundy (New Haven – London: Yale University Press, 2010). ↩︎

- Saul, English Church Monuments cit.: “By the fourteenth century the use of chests to indicate monuments of high status had become de rigueur. The principal attraction of the chest was that it raised the effigy up, making it the object of attention. A further advantage was that it provided space around the sides for the deployment of heraldry or religious imagery. […] The tomb chest was but one of a range of devices by which the highest‐ranking patrons could draw attention to their monuments. The most eye‐catching of all was the canopy. In medieval architecture, it was the canopy which carried the strongest associations with sanctity and holiness, and which did most to invest a monument with status.” ↩︎

- Alabaster from the north Midlands began to replace Purbeck stone from the mid 14th century. ↩︎

- Binski, Medieval Death cit., p. 101. ↩︎

- William de Ramsey was credited with inventing the English Perpendicular style; alongside his father John de Ramsey, William worked on the cloister and St Ethelbert’s Gate in Norwich cathedral, on the chapter house at Old St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and the presbytery of Lichfield Cathedral. ↩︎

- Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture cit., p. 56: “Sir Roger Kirdeston […] may have easily been killed in the first engagement of the Hundred Years’ War, the invasion of Catzand, an island strategically important in that it blocked the mouth of Oosterschelde and was situated almost directly across from Sir Roger’s native Reepham”. ↩︎

- Cf. J.M. Luxford, ‘Ex terra vis: the cadaver brass of Richard and Cecily Howard at Aylsham’, in Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society 20 (2019), pp. 64-79. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 75-9. ↩︎

- Cf. J. Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1984); C. Burgess, ‘”A fond thing vainly invented”: An Essay on Purgatory and Pious Motive in Later Medieval England’, in S.J. Wright (ed.), Parish, Church and People: Local Studies in Lay Religion, 1350-1750 (London: Harper Collins, 1988), pp. 56-84. ↩︎

- Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory cit., p. 357. ↩︎

- Saul, English Church Monuments cit., chapter 6. ↩︎

- J. Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (London: Edward Arnold, 1924), p. 126. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 134-5. ↩︎

Leave a comment