I shall obtain my independence only by persevering and by making no secret of my intention of emancipating myself.

In a brilliant essay, Griselda Pollock famously pointed out how the spaces that defined modern painting – or the painting of modern life, “the nude, the brothel, the bar”, were inextricably linked to masculine sexuality. This “historical asymmetry” was the result of “social structuration of sexual difference” and determined what and how men and women painted.1

The recent exhibition Berthe Morisot. Impressionist Painter at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Turin (16 October 2024 – 9 March 2025) offers more than a selection of works wrapped in a blockbuster package. The French impressionist painter is not only seen through the eyes of her curators, Maria Teresa Benedetti and Giulia Perin, but also through the lens of a living artist, Stefano Arienti (Asola, 1961). The “spaces of femininity” identified by Pollock – “dining-rooms, drawing-rooms, bedrooms, balconies/verandas, private gardens” – are indeed not only evoked in the subject-matter of the works on display, but re-enacted in the visual cues and props chosen by Arienti.2

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot (1841-1895) was born into an upper-class family in Bourges. Her affluent social background meant that she was more likely to enjoy her family’s support in pursuing her artistic proclivities. When she began her artistic training, women were still not allowed to attend the Académie, so private tutoring was the only viable option for Berthe. Upon arriving in Paris in 1855, Berthe and her sister Edma Morisot (1839-1921), who had also shown artistic potential, both took private lessons from Joseph Guichard (1806-1880), a painter who had trained under Ingres. The two sisters made quite the impression on Guichard, who felt compelled to warn their father that their talent exceeded minor “drawing-room accomplishment” and that they ‘risked’ becoming actual painters!

Do you realize what this means? In the world of the grande bourgeoisie in which you move, this will be revolutionary, I would even say catastrophic. Are you sure that you will not come to curse the day when art, having gained admission to your home, now so respectable and peaceful, will become the sole arbiter of the fate of your two children?3

In 1860, the Morisot sisters would move on to study under Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), a painter from the Barbizon School who taught them to paint en plein air. Corot introduced them to another painter, Edouard Manet (1832-1883), who will play an important part in their professional as well as personal lives. Berthe would marry his brother, Eugène Manet (1833-1892), also a painter, albeit less successful than his brother or his wife. Edma, in turn, would go on to marry in 1869 a close friend of Edouard Manet, the naval officer Adolphe Pontillon, though marriage in her case was fateful to her career as a painter. Few works by Edma survive and they consists mostly of landscapes in the Barbizon style and portraits of her sister. Berthe, too, immortalised Edma in a number works – including her best known painting, The Cradle (1872).

Berthe Morisot’s father did not take heed of Guichard’s warning and, on the contrary, after his daughter’s acceptance at the Salon in 1864, he even built a studio for her in the family gardens. Berthe met Manet when she was copying masterpieces at the Louvre and in 1868 started frequenting his studio. Even though her reputation as a painter was growing, she modelled for Manet and was featured in several of his works. She appeared most famously in The Balcony (1868-9) of which she wrote to her sister: “In The Balcony I am more strange than ugly. It seems that the epithet femme fatale has been circulating among the sightseers.”

The nature of Manet and Morisot’s initial relationship is not fully clear. Models and painters were often lovers, but things obviously changed when Morisot married his brother Eugène. Manet’s failure to acknowledge her talent, however, remained constant, seeing Berthe more as a muse than a painter. Needless to say, she struggled to assert her independence. A telling example of Manet’s patronising attitude was when, in 1870, he heavily retouched a work that Berthe was going to submit to the Salon, turning it into a “caricature” – as she wrote to her sister. Unshaken in her determination to succeed, Morisot persevered, fully confident in her artistic ability as her defiant words testify:

I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, and that’s all I would have asked for because I know my worth.

Morisot lived during what Frances Borzello termed the “glory days”, when becoming an artist was no longer wholly inconceivable for a woman, a fact that was normalised in many portraits of female artists at work.4 While academic training became available only towards the end of century (the Ecole des Beaux-Art allowed women in 1897), there were other opportunities for aspiring female artists, as the story of the Morisot sisters goes to show.

Morisot joined the Impressionists since their first independent show in Nadar’s studio in 1874, and participated in almost all of their subsequent exhibitions until the last one in 1886. In the same 1874, she married Eugène Manet and together they had a daughter, Julie, in 1878. Marriage and motherhood often stood in the way of women’s artistic career. Berthe was lucky that her husband did not make her give painting up, though some episodes reported by the artist would suggest that he was not always supportive. When the couple was staying on the Isle of Wight, Berthe apparently stopped sketching on the spot because the wind made her hair look unkempt, which greatly upset her husband. She still fared better than her sister Edma whose spouse forced her to make an inevitable choice that she came to regret.5

Like other fellow Impressionists, Morisot embraced the ambition to paint en plein air rather than in the studio, a technique that allowed her to capture fleeting light and colour effects. Moreover, the scope of themes preferred by Impressionist painters was “comfortable” for women:

The flowers, women, children and locations of a pleasant domesticity were easily accessible, and it must have been liberating for women to be able to explore subjects that were close to home yet also favoured by the men in their group.6

Although influenced by Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Monet, Morisot developed her own signature style consisting of long, fast and loose brushstrokes, often applied directly on the canvas without a preparatory drawing. Her paintings have been described as “informal” in both content and style: the immediacy of her scenes results in the unfinished quality typical of other Impressionists. The atmosphere of “ease and relaxation” pervading her compositions, however, belied one of “melancholy and introspection”.7

Morisot’s body of work spanning still lifes, landscapes, interiors, portraits, and nudes, is amply investigated in the exhibition with four sections devoted to paintings depicting the family sphere, female portraits captured in both intimate moments and social settings, landscapes and gardens, and figures in nature. Morisot also approached other media beyond oil painting, such as watercolour, pastel, and engraving, which was not untypical for female artists. Those techniques were more economic, used smaller formats, belonged to the lesser genres women were expected to practice, and implied either the painstaking intricacy or the lightness of touch associated with the feminine – as opposed to the ‘vigorous’, ‘bold’ and by definition ‘masculine’ brushwork of painting.

The opening room features images of paintings by Edouard Manet painted over by Stefano Arienti as though to mimic the master patronisingly retouching Morisot’s works. Among these modern palimpsests are the copies of two famous portraits featuring Berthe: The Repose (1869-70) and Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets (1872). In these paintings, Berthe is shown in the two polarised female tropes of “woman in white” and “dark lady”, embodying the domesticated, virginal femininity in opposition to the dangerous, seductive, sexual figure. More especially in The Repose, Griselda Pollock observed that these contrasting iconographies appear combined. Berthe is in fact both the respectable, upper-class woman in white, and the eroticised enchantress as the reclined posture on the sofa would imply.8 The ambiguous depiction (befitting the unclear relationship between the painter and his subject) was lampooned by the contemporaries who called the painting ‘dirty’ and ‘in bad taste’, but it was also seen as a symbol of the two sides of modernity, the “dreamy bourgeoisie” and the ennui and melancholy described by Baudelaire.9

Arienti’s curatorial imprint continues in the following four sections adding visual elements, textures, and objects taken from Morisot’s works, such as ribbons, wallpaper strips, a piano, a coat rack. Their purpose is to offer a suggestion of the period and enhance the visitor’s sensory experience. Contemporary artists as co-curators are extremely effective, especially when their interpretation is thought-provoking or even challenging. Arienti is a self-professed ‘intruder’, and he does a very stealth job of it, leaving behind cues that titillate the visitor. Is he a mindful burglar who fluffed the cushions as he went, so to speak? Or is he an artful proxy for the real trespasser, the (modern) viewer?10

Any consideration, however, should not undermine the quality of the Turin show or its thoughtful curation. Ideas shape exhibitions as much as budget, sponsors, lending institutions, conservation requirements, insurance, space, public, and so forth, factors that are too often overlooked when reviewers suggest bigger, better, and bolder alternatives.

Decades of feminist criticism have shown that the work of a female artist is invariably judged against her resilience in overcoming social barriers. Even when academies finally opened their doors to female students, women could not attend male nude classes on grounds of morality and propriety. Their study of the human body was only based on observing partially draped female models or copying nudes in museums. Even when women were finally admitted to life drawing classes, fully nudity was still prohibited and male models had to cover their manhood.11 This educational disadvantage precluded them from undertaking more noble and serious genres like history and mythological painting – except for a few brave attempts to break the glass ceiling.12

Morisot was not alone in her struggle for self-affirmation, not even within the Impressionists which also included Eva Gonzalès (1849-1883), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916). These women made their way into the group mainly through talent and ambition, but also thanks to their personal links with fellow artists and critics who gave them access to intellectual circles. Women painting and sketching en plein air or copying from old masters in museums (the closest they could get to studying human anatomy) became a fairly popular subject depicted by male artists with notable examples including Manet, Degas but also the macchiaiolo Giovanni Fattori. Rather fittingly, the painting Le allieve (1885) by Lorenzo Delleani from GAM’s permanent collection featured in the exhibition is a welcome addition, which can also be seen as a reference to Fattori’s Young Woman Painter at Work (1893, private collection).

Being ‘given’ a seat at the table – or invited to the dinner party as Judith Chicago would put it – did not equate to winning the war. Prejudiced views still prevailed and the best compliment a woman could receive was that she could paint ‘like a man’. Thus the painter Henri Fantin-Latour wrote to Manet in 1878:

The Morisot girls are charming. It is a pity they are not men. However, as women, they could further the cause of art by each marrying an academician and stirring up trouble in the camp of these old fogeys.13

Although later female artists did not always believe it a valid or fair distinction, commentators often focused on how the same subject is approached by the male artist as opposed to a woman. Motherhood tends to be represented in a less sentimental way, women sitters not as coquettishly but as individuals. The feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, however, warns against the perils of a strictly deterministic connection: “gender difference, however, must not be interpreted as directly expressed in the work in terms of some formal structure or inevitable iconographic choice; nor should gender be understood in terms of essential, fixed, timeless, inborn qualities of masculinity or femininity.” More importantly, “gender can only signify through the concrete qualities of pictorial language in specific situations.”14

Bearing this proviso in mind, the visualisation of the female body is where gendered perspectives become the most palpable. Female nudes are sexualised by the male gaze, they offer themselves as objects to be looked at and to fantasise about. Women artists, conversely, capture their subject in more intimate and private moments, often looking away, as though unaware of the viewer. Beyond the appearances of a beautiful, available body, they depict their sisters as thinkers, wrapped in their own thoughts or reveries, caught up in the complexity of their mind.

Self-withdrawal, when female sitters were painted by men, on the other hand, has been interpreted as a sign of their passive emotionality and inner anxiety, juxtaposed to the heroic presence of their male counterparts. Alternatively, female subjects could stare directly into the viewer’s eyes, defiant, determined, and self-aware. Or they could take on the “power of the gaze”, like the opera-goer in Mary Cassatt’s In the Loge (1878) who takes on the role of the active beholder. Her role as empowered viewer clearly contrasts with the passive stance of the woman painted by Auguste Renoir in The Loge (1874) only a few years earlier, who has lowered her opera glasses in a metaphorical act of submission.15

The same “power of the gaze” can be recognised in Woman with a Fan (At a Ball), a painting presented by Berthe Morisot at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. The lady is seated and observing what is happening in the ball room. She is holding a fan, a proverbial female prop, held up next to her face in a gesture signalling demure. The amorous scene depicted on the fan in a vaguely rococo style possibly hints at the woman’s voyeuristic intent. Even more unapologetically assertive is Morisot’s own “power pose” in the portrait painted in 1875 by her friend Adèle d’Affry, duchesse de Castiglione Colonna, also known as Marcello (1836–1879). Dressed in a pink peignoir, a light dressing gown worn by women before or after taking a bath, Morisot deliberately turns towards the viewer as though they are intruding on a private moment. Firmly clasping a folded fan, she is unabashedly at ease, maybe because she is in a “space of femininity”.

Between 1874 and 1877, Morisot painted many “toilette scenes”, capturing women in their domestic interiors combing their hair, dressing or undressing, gazing into the mirror. This was a very popular subject appreciated by male artists, too, including Morisot’s closest and most admired colleagues, Manet, Renoir, and Degas. The lingering eroticism exuded in their renditions, however, differs from the subtle, rarefied, lyrical atmosphere of her Woman at her Toilette.

Morisot developed an interest for the nude form observing the Venuses and odalisques painted by François Boucher and Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres. Her mentor and brother-in-law, Manet, had created two of the most controversial nude scenes of their time, Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia, but for a woman – and especially a distinguished upper-class woman such as Morisot – to paint those subjects was simply unthinkable. Between 1884 and 1885, however, Berthe began to draw female nudes from life in the privacy of her home. Fortunately, she had the support of her husband who even purchased his brother’s Nude Combing Her Hair. Manet had passed away – according to some, this was partly why Berthe took on this new challenge – but his painting hung in the studio and provided her inspiration for her drawings. In her exploration of the human form, Morisot was also encouraged by another painter and friend, Renoir. Morisot regularly frequented his atelier and she was awestruck by the “subtlety and gracefulness” of his nude bathers. But above all, Renoir convinced her that “the nude is absolutely indispensable as an art form.”16

Morisot discretely began to work on nude figures and found a professional model, the red-haired Carmen Gaudin, who also posed for Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Her first composition, Nude from the Back, was modelled on Ingres’s odalisques while the soft, evanescent contours diffused the sexual charge of his orientalist paintings.

In the late 1880s, Morisot decided to experiment with new media and took on sculpture and drypoint etching. She employed another model who had been recommended to her by the artist Federico Zandomeneghi. Her name was Marie-Jeanne Fourmanoir and she posed for Jeune fille au repos, a study later reproduced in a series of eight drypoint prints made by the artist in 1888-89. Featured in the Turin show was a version from the collection that once belonged to Jacques Doucet (1853-1929) now at the INHA library in Paris. In this exquisite work, the young lady is reclining on a sofa with her head resting on her hand in a pensive way. The artist concentrated on the face, hair, and settee rendered with quick, impressionistic touches, while the rest of her figure was prudently left unfinished. When compared to a painted version of the same subject, Young Girl Lying Down, some compositional differences stand out, namely the body slightly turned towards the viewer and her hand deliberately touching her hair. The sitter’s pose thus appears more natural, less stifled by artistic or social conventions, and in some ways more erotic.

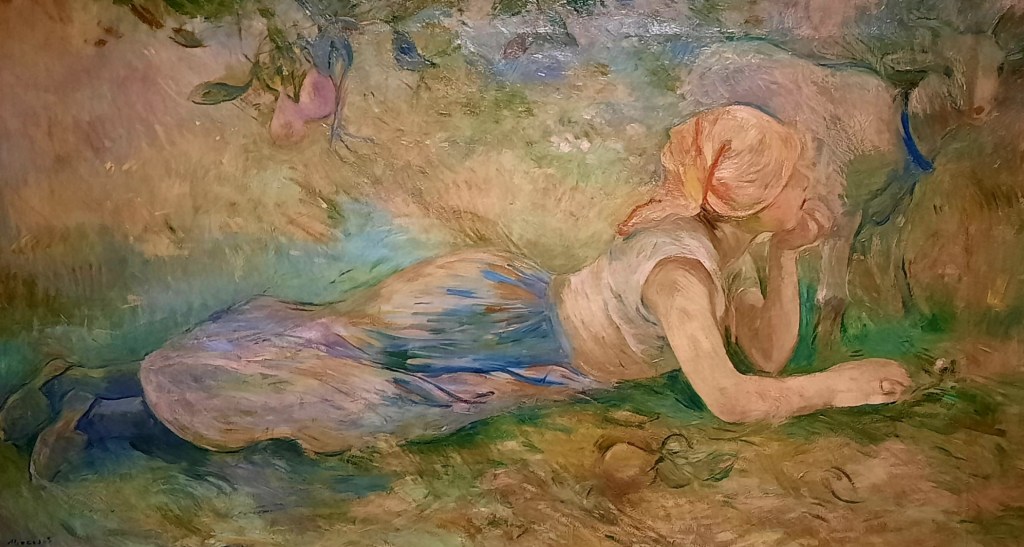

Between 1890 and 1891, Berthe, with her husband Eugène and her daughter Julie, rented a house in Mézy-sur-Seine, a village situated some fifty kilometres west of Paris. There Berthe painted several views of their orchard and the surrounding rural landscape. This rustic setting inspired her to work on pastoral themes, namely on a composition featuring a young shepherdess reclining on a meadow with a goat by her side. Both nude and clothed versions of the same subject exist and the show in Turin offers the unique opportunity to see two of them facing each other.

In reinterpreting this classical pastoral subject, Berthe was partly influenced by the idyllic scenes perfected by her mentor, Camille Corot. Departing from the latter’s idealised, italianate pastoral visions, Morisot’s naturalistic depiction also pays tribute to the realism of Jean-François Millet – incidentally, at a time when Vincent Van Gogh was copying the French master. A young local girl who was friends with her daughter, Gabrielle Dufour, posed for the shepherdess resting the grass either nude or wearing a red headscarf, a white vest, and a lavender skirt. The painter developed each element very carefully, the landscape, the goat, the girl, over numerous individual studies. Renoir’s Large Bathers, completed in 1887, served as a model for its voluptuous female shapes, its warm and bright palette, and its impressionistic landscape. During those years, Renoir was undoubtedly Morisot’s main interlocutor and he visited her in Mézy as she was working on these pastoral paintings. The two artists regularly discussed ideas, worked on the same subject-matters, and even shared the same models. Morisot’s view of the Seine in the background could be interpreted as an echo of Monet’s ethereal aquatic visions. This relation, however, ought to be reversed as his famous Water Lily series was, according to their mutual friend, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, inspired by Morisot’s “white water-lily done with the famous three crayons”.17

Any constraint on the painter’s freedom to represent female sexuality seems to have dissipated after her husband Eugène died in 1892. It was as though Morisot felt relieved of the pressures exerted not only by family, but also friends, mentors, and male colleagues. This new, liberated approach can be seen in her most ambitious and accomplished painting, The Cherry Tree, which concludes the exhibition in Turin. Morisot began working from life on this canvas in Mézy in 1891 and finished it in Paris three years later. Morisot initially had her daughter Julie pose for the young woman perched on a ladder picking cherries. Once back in her studio in Paris, she decided to complete the composition using a professional model, Jeanne Fourmanoir, instead. This replacement must have encouraged Morisot to be bolder and imbue the painting with “unalloyed sexual pleasure”.18

Following her posthumously acquired iconic status, Morisot became synonymous with a female way of seeing. A case in point is the poem Seeing a Woman as in a Painting by Berthe Morisot by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, where her archetypical feminine subject is conjured as the embodiment of beauty, love, and time. In Ferlinghetti’s poetic vision, the hourglass of her silhouette is both a symbol of aesthetic/physical perfection and a foreboding metaphor of its inevitable decay. Though gendered and gendering this allegorisation may be, a few lines in the poem seem to capture the essence of the woman painted by Morisot: “unaware of your self/ full/ of breath and life/ not yet/ awakened”.19

- G. Pollock, ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, in Vision and Difference. Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art (London – New York: Routledge, 2003), 54-55. ↩︎

- Ibid., 56. ↩︎

- Quoted in M. Howard, Enclyclopedia of Impressionism (San Diego: Thunderbay Press, 1997), 150. ↩︎

- F. Borzello, A World of Our Own. Women Artists Against the Odds (London: Thames & Hudson, 2024), pp. 157-219. ↩︎

- Cf. Berthe Morisot, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot (London: Percy Lund, Humfries & Co, 1959), 27. In a moving letter to her sister dated 15th March 1869, Edma wrote: “In my thoughts I follow you about in your studio, and wish that I could escape, were it only for a quarter of an hour, to breathe the air in which we lived for many long years.” ↩︎

- Borzello 2024, 200. ↩︎

- Howard 1997, 151. ↩︎

- G. Pollock, ‘A Tale of Three Women. Seeking in the dark, seeing double, at least, with Manet’, in Differencing the Canon. Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London – New York: Routledge, 1999), 249-250. ↩︎

- Ibid., 258-60. ↩︎

- One may be reminded of what the French contemporary artist Christian Boltanski once said – “When a museum invites you to come and make an ‘intervention’, it is no longer an intervention”. C. Boltansky, talk given at Henry Moore Sculpture Studio, Halifax, 1995. ↩︎

- The Royal Academy capitulated in 1893 and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1897, cf. Borzello 2024, 216-17. ↩︎

- Women being excluded from nude classes was famously the reason why there had not been any great women artists, according to Linda Nochlin. ↩︎

- Letter dated 26 August 1878, quoted in P. Courthion, Manet (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 86. ↩︎

- L. Nochlin, ‘Issues of Gender in Cassatt and Eakins 1860-1900’, in S.F. Eisenman (ed.), Nineteenth-Century Art. A Critical History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2020), 388. ↩︎

- Nochlin 2020, 397. ↩︎

- Quoted in M. Shennan, Berthe Morisot: The First Lady of Impressionism (Guildford: Sutton Publishing, 1996), 234. ↩︎

- Shennan 1996, 267. ↩︎

- Ibid., 272. ↩︎

- L. Ferlinghetti, ‘Seeing a Woman as in a Painting by Berthe Morisot’, in Over All the Obscene Boundaries. European Poems and Transitions (New York: New Directions, 1984), 20-21. ↩︎

Leave a comment