The Ladies of the Vale that aim to ‘aspire’

The Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Chad in Lichfield (Staffordshire) was built in the early 13th century and completed in the mid 1330s. Its unusual three spires, named the “Ladies of the Vale”, are its prominent feature. Indeed, there are but three cathedral of this kind in Britain and Lichfield is the only mediaeval example.

Lichfield diocese rose to prominence in the 8th century when it was a brief period declared England’s second archbishopric. Its history is tied to Chad of Mercia, an Anglo-Saxon monk who converted the region in the 7th century. Under Norman rule, however, Lichfield lost the see to nearby Chester and Coventry, and the church went into a slow decline. The chapter was subsequently reconstituted by Roger de Clinton in 1130. The rebuilding of the cathedral reached its climax in the late 13th century, when Edward I’s trusted treasurer, Walter Langton, was appointed bishop in 1296. No expenses were spared for his ambitious plans: a new golden shrine for St Chad was commissioned, the west front was remodelled, and the Lady Chapel was erected. What is more, Langton transformed the church into his fortress complete with walls, gatehouses, and a moat.

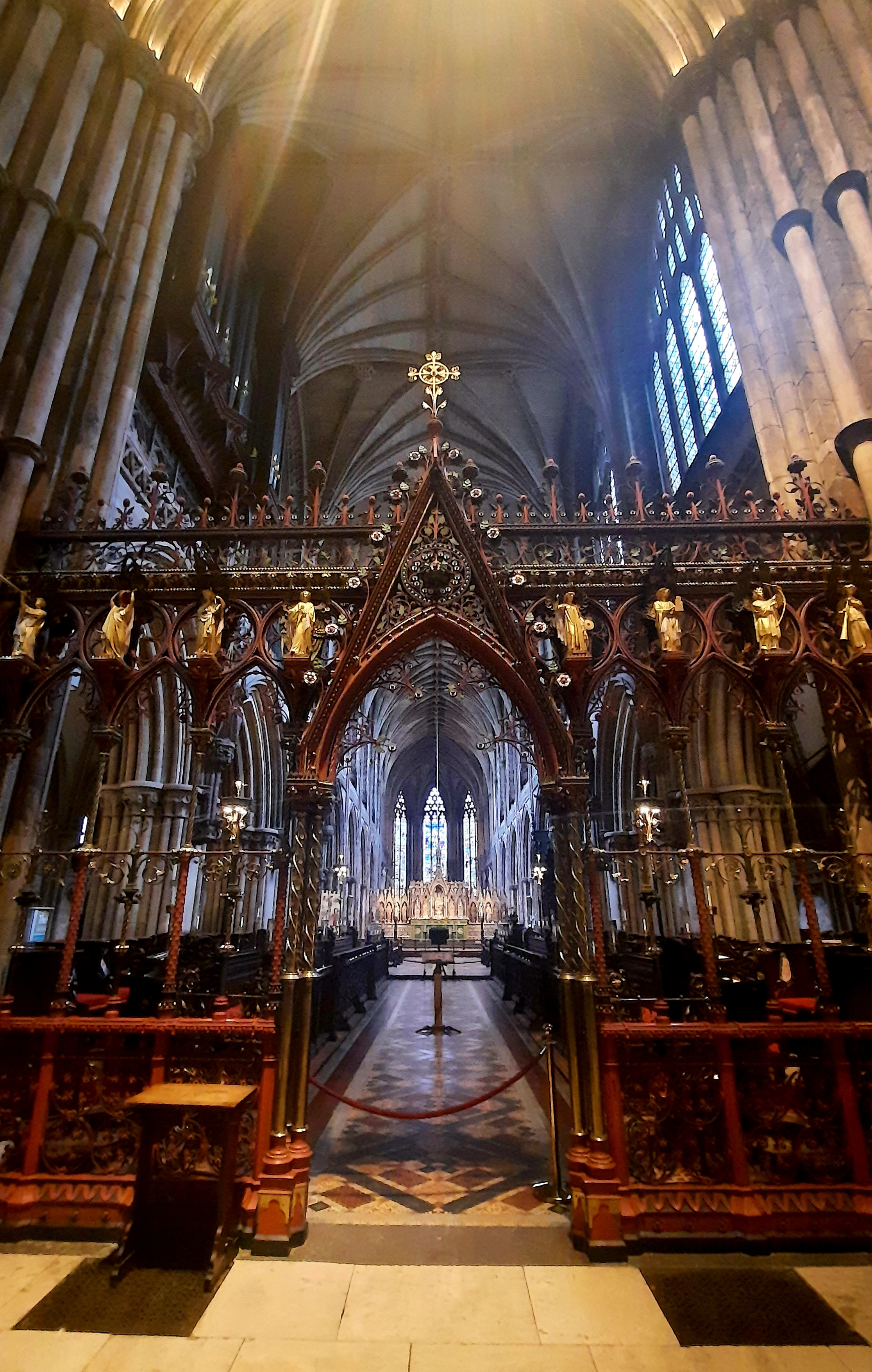

Not unlike many Gothic churches, Lichfield cathedral suffered severe damage during the Civil War when it was besieged three times by the Royalists. As a result, the church was extensively renovated between the late 18th and the 19th centuries. The first remedial conservation work on the roof and the carvings was undertaken by James Wyatt (1746-1813) between 1788 and 1795. Then, in 1856, the famous Victorian architect, George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), proceeded to rebuild the church in a sympathetic Gothic style. The west front was renovated following the principles of Gothic Revival. The carvings of kings and queens vandalised during the Civil War were repaired in few instances and for the most part replaced with modern replicas. But the Victorians also updated the series with new statues like the effigy of Queen Victoria carved by her daughter, Princess Louise. Scott also designed a new metal screen for the choir that was made by the famous metalworker from the Midlands, Francis Skidmore (1817-1896), between 1859 and 1863.

Langton’s greatest accomplishment was the polygonal Lady Chapel, often compared to the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. While its polygonal apse is more typical of continental Gothic, its large decorated windows also tell an interesting story. Dating from ca. 1530, the stained glass originally came from a monastery in Herkenrode, Belgium. In 1803, a Derbyshire aristocrat and poet, Sir Brooke Boothby (1744-1824), secured 300 panels from Herkenrode Abbey and sold some of the glass to Lichfield cathedral. After a long journey from Liège to Hull, they made their way to Lichfield’s Lady Chapel. As the measurements did not fit, the stonework was altered to accommodate the panels. Juxtaposed to the Belgian decorated glass are the windows designed by Charles E. Kempe (1837-1907). More or less seamlessly, the 16th-century style of the former can be compared to its Pre-Raphaelite revival.

Old stained glass windows from continental disbanded monasteries became popular with British collectors in the mid 18th century. The vogue was started by Horace Walpole (1717-1797), whose collection of old stained glass at Strawberry Hill totalled to a staggering 450 pieces. After the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, continental stained glass surfaced on the market and was readily bought by the English gentry to decorate their homes. Because of the success among British collectors, art dealers – like Norwich-based John Christopher Hampp (1750-1825) – began to specialise in the export of painted glass. The demand and appreciation for mediaeval glass further increased with the restoration of religious buildings undertaken in Victorian times.

The Lichfield Angel is a remarkable survival of early mediaeval sculpture. Uncovered during restoration work in 2003 under the nave, the Angel came from St Chad’s original stone shrine built by Hedda in 800 AD. The carving depicting the Archangel Gabriel probably belonged to St Chad’s chest alongside another panel with the Virgin Mary as part of an Annunciation group. Its exquisite quality can be appreciated in the fine detail of the wings, the wavy folds of the drapery, and the traces of red and white pigment.

In his architectural survey of Great Britain, Nikolaus Pevsner seems rather unconvinced by Lichfield’s cathedral: “if spires are meant to aspire, these aspire too little. […] Lichfield, like Wells, can’t make up its mind. Also, the portals are too small to join in as separate voices. […] All the statues seem in danger of floating on the surface…”1

Lichfield cathedral undoubtedly stands as a testament to its troubled history of rise and fall. As Simon Jenkins observed, “Lichfield is not so much a mediaeval cathedral as a resurrected one”.2 The feeling of slight disappointment for its spurious character is quickly replaced by fascination with the Victorian approach to conservation. The overriding question must ultimately be – where does philology end and interpretation begin?