Lolloping along is normally referred to animals moving in an awkward, rolling way. In Norfolk dialect, however, this expression can be used for people as it simply means ‘to progress slowly in an ungainly manner’. As it were, these scattered notes and postcards are the result of idle meanderings, lolloping along in the East of England.

Owing its name to the Germanic people of the Angles, East Anglia was one of the original Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms of the Heptarchy. Formed in 520, it merged the region of the North and South Folks with the Isle of Ely, corresponding to modern day Norfolk, Suffolk and northern Cambridgeshire. The Angles had settled in the area previously occupied by the ancient tribe of the Iceni whose legendary queen Boudica launched a bloody revolt against the Romans in 60-61 AD. The Kingdom of the East Angles reached its apogee in the 7th century and lost its independence to Edward the Elder and the Kingdom of England in 917. Alluvial arable land ensured farming prosperity for the region and Worsted sheep provided a strong, smooth yarn that ensured a prosperous textile industry throughout the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. While the Industrial Revolution shifted the productive focus to the Midlands and the North, East Anglia largely remained a farming region of landed gentry and country estates.

Wetland and waterways perhaps constitute the most defining element of East Anglian landscape. Marshland routinely brushed by the tides on the coast and the rivers and a system of man-made canals inland offer an ideal habitat for plants and animals as well as an idyllic subject for many landscape artists.

The low-lying landscape under the expansive, ever-changing East Anglian sky famously inspired Suffolk-born John Constable (1776-1837) to paint his native Dedham Vale. This is how Constable described native East Bergholt: “The beauty of the surrounding scenery, its gentle declivities, its luxuriant meadow flats sprinkled with flocks and herds, its well cultivated uplands, its woods and rivers, with numerous scattered villages and churches, farms and picturesque cottages, all impart to this particular spot an amenity and elegance hardly anywhere else to be found” (Memoirs of the Life of John Constable…, London 1845, p. 1).

The famous Norfolk and Suffolk Broads originated from man-made peat deposits from the Saxon age that were flooded by rising sea levels in the 14th century and subsequently used as fisheries. As Ernest R. Suffling wrote in The Land of the Broads (1885): “There is no need to go to Holland for a sketching-ground […]. Here are the flat, green plains, with the river simply kept within bounds by its banks […]. Here are the windmills and wherries, the red and white cattle, and the picturesque peasantry, simply wanting to be transferred to canvas.” With their windmills, canals, locks, barges, grazing livestock, and marshes, the Broads offered the ideal setting for painters. The perfect lens to capture this Dutch-like landscape could be found in the illustrious precedent of the Dutch Golden age. Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682) and Meindert Hobbema (1638-1709), in particular, served as a model for the artists of the famous Norwich Society of Artists (1803-1833). Led by John Crome (1768-1821), John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) and Joseph Stannard (1797-1830), this group of artists set out to paint en plein air views of Norwich and the surrounding countryside. Their works displayed in the annual exhibitions organised by the Norwich School were admired by French Impressionists.

“The visitor to the Broads can be startled by the sight of sails apparently gliding through the reed beds in a landscape where the water is not immediately visible.”

N. Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Norfolk (1962)

Alfred Stannard, On the River Yare 1846, oil on canvas, Norwich, Norwich Castle and Art Gallery; Photo: Norfolk Museums Service

Churches

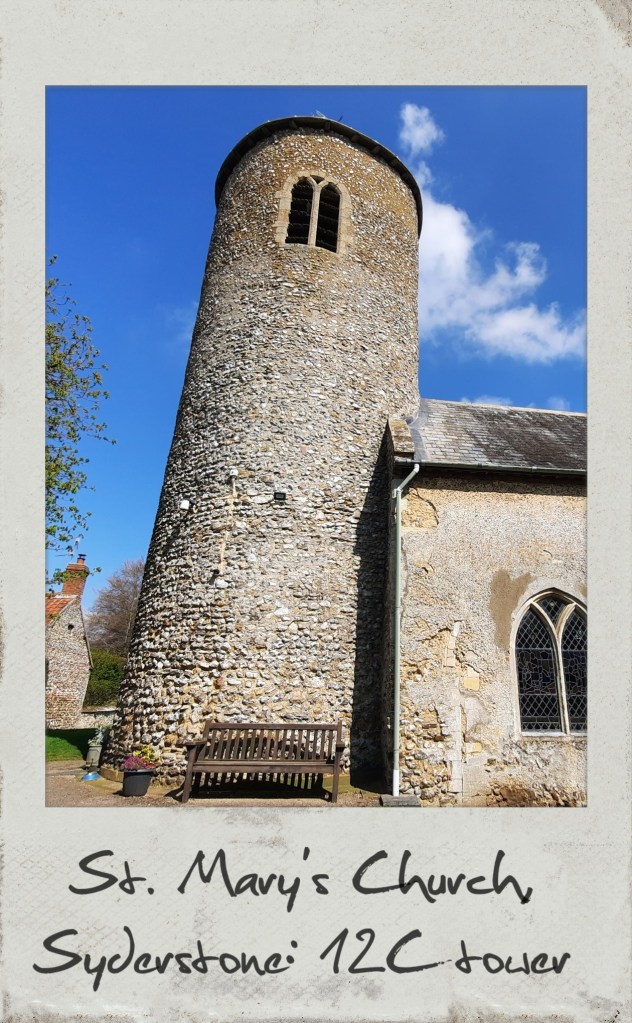

“To the student of the various styles of architecture there is an ample field for exploration, as the different churches will take him from the twelfth, through the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries […]. I would particularly call attention to the Round Towers to be found in several parishes, and which are ascribed to the Saxon or Danish period: many of them were, after the Norman conquest, surmounted by an octagonal upper storey. Most of the Norfolk churches are constructed of flint, as very little building stone is found in the county […].”

E.R. Suffling, The Land of the Broads (1885), pp. 3-4

Most books about Norfolk list the staggering number of churches amongst the most characteristic facts about this county. With over 650 examples, the church density is actually quite remarkable.

Another statistic record held by Norfolk is the highest number of round towers in England (124 out of 185 existing towers). Round towers were typical of Saxon religious architecture, although they continued to be used also after Norman features made their way into indigenous architecture. Architectural historians have come up with different theories for the exceptional use of round towers. As they are normally found in areas subject to plundering, they could have originated from defensive structures, and the church buildings were a later addition. Others point to the fact that they are found in areas that lacked of good building stone for quoins, as was the case for Norfolk. Others argued that this concentration was instead dictated by a stylistic preference based on a common cultural pattern round the North Sea.

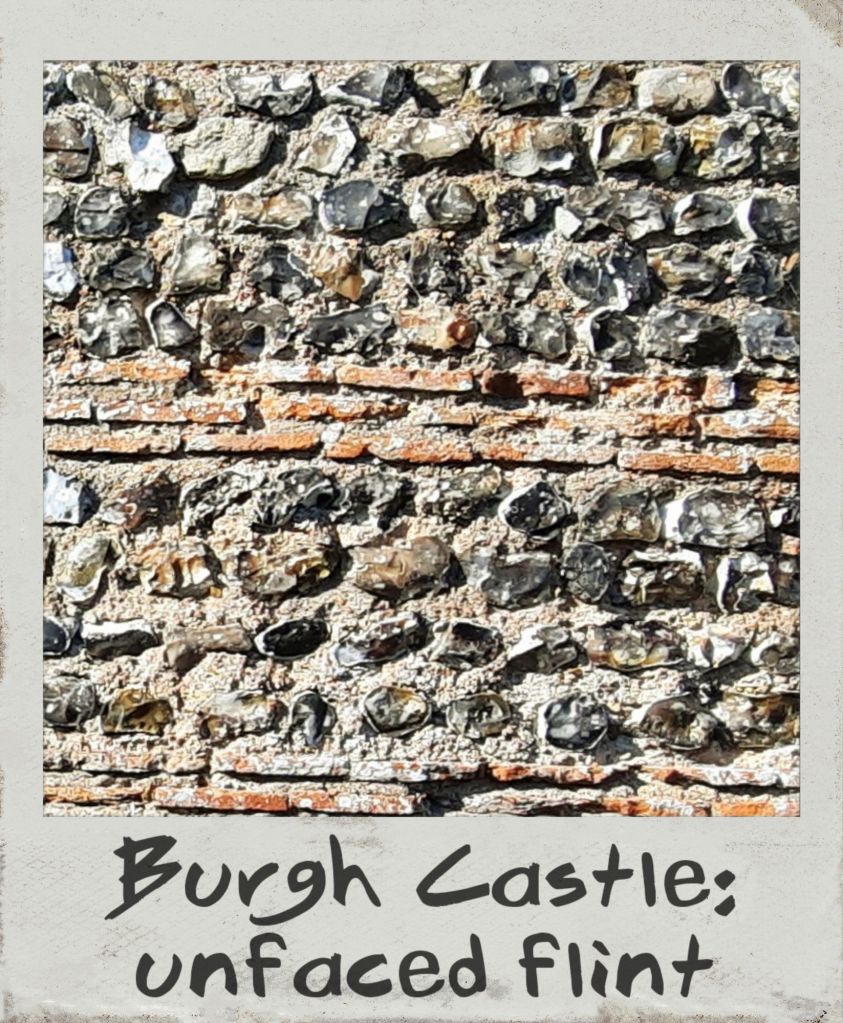

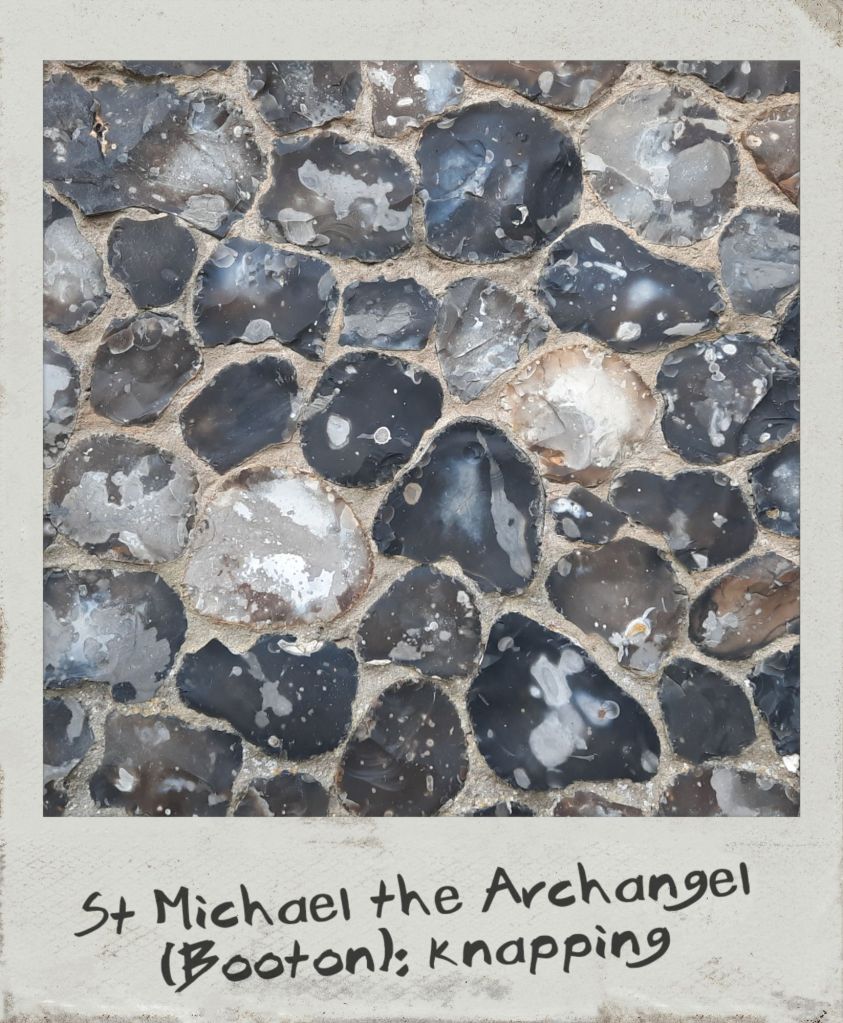

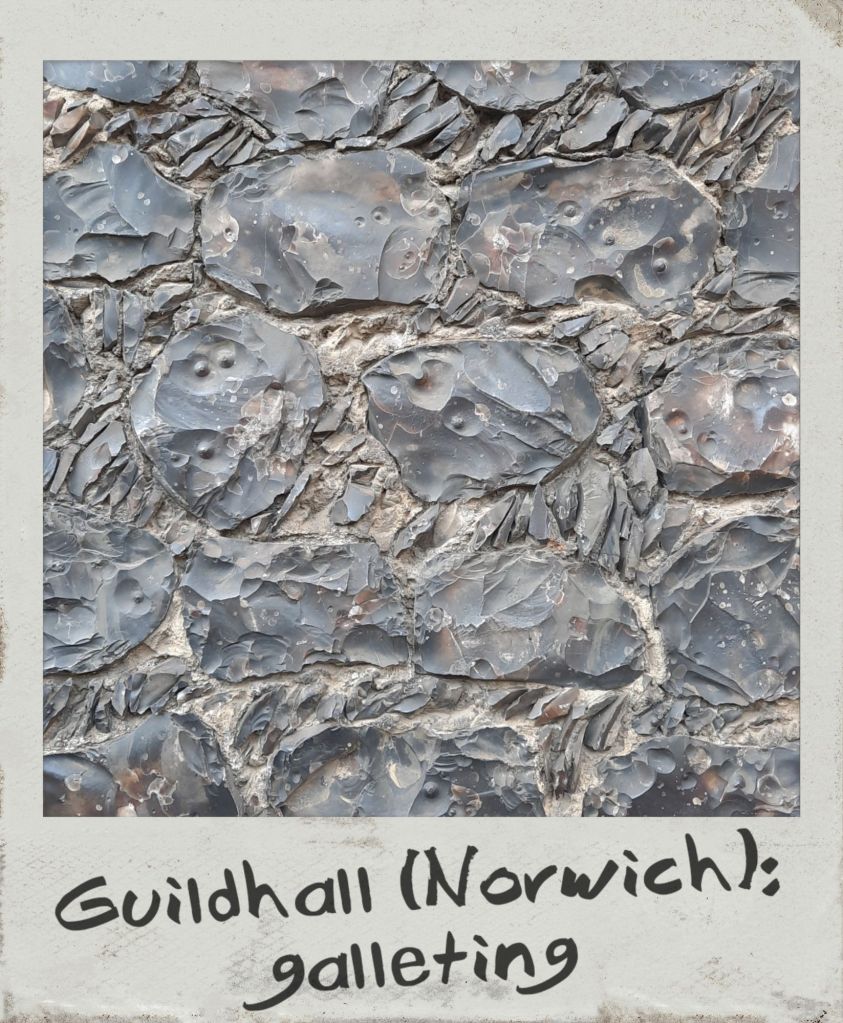

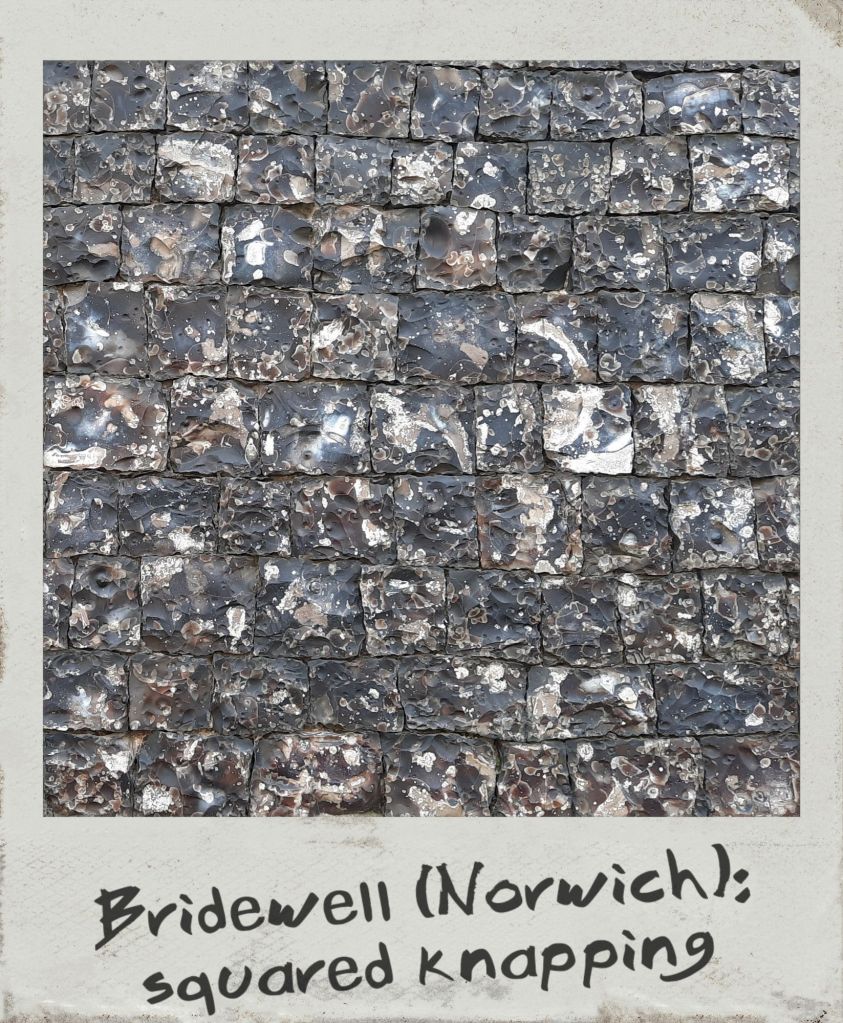

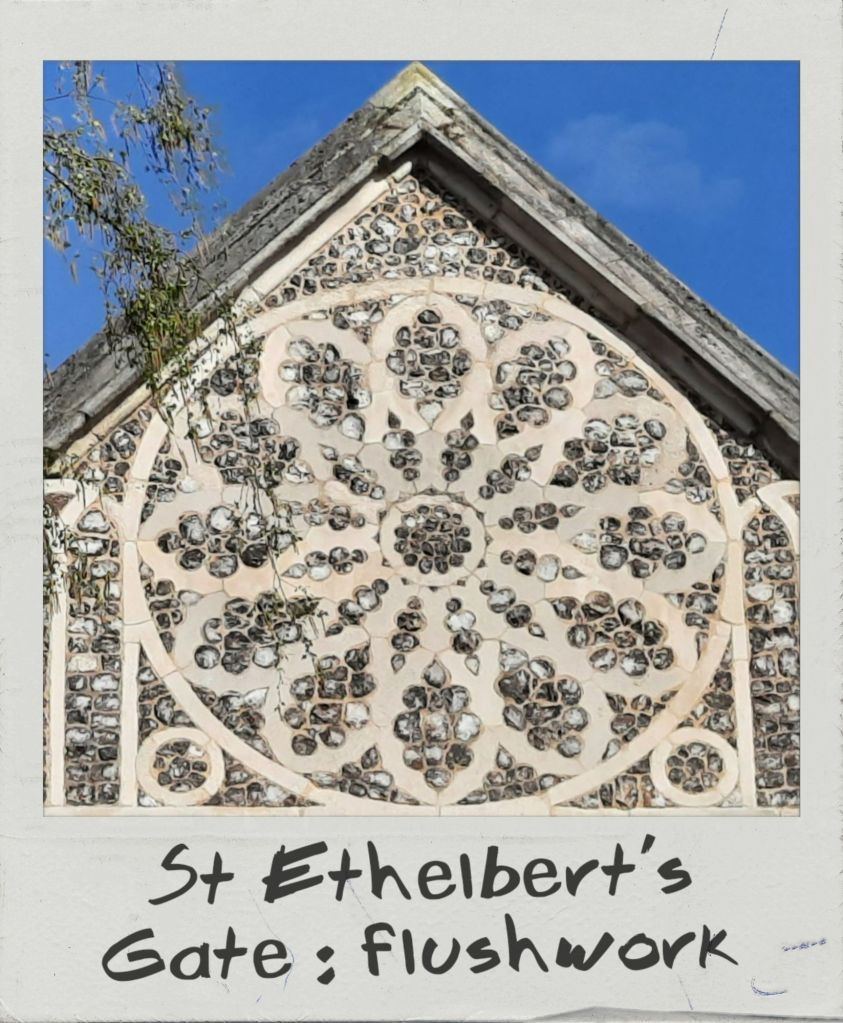

Norfolk architectural landscape is historically synonymous with its ubiquitous building material: flint. This nodular, crystalline stone originates from sedimentary rocks such as chalk or limestone and is composed of quartz in varying degrees of purity. As a result, flints may range of colours, from white or light grey to brown and black. Naturally found in fields or on beaches, this readily available and very durable mineral was already used in constructions by the Romans. Unfaced flint embedded in mortar was the first most common application, as can be seen in the Late Roman fort of Burgh Castle. By the 14th century, new techniques turned flint into a more polished and decorative material. Knapping involved smoothing one face and tapering the back to obtain a cone bedded into mortar. Galleting allowed to mask the mortar by pushing small flakes of stone in the interstices between flints. The most refined (and expensive) method was squared knapping, where flints were squared to obtain a uniform surface with almost no mortar infill left exposed. Beyond the decorative purpose, these techniques were perfected essentially to protect the mortar from deteriorating. Flushwork, on the other hand, consisted in creating ashlar panels with cut-out shapes filled with squared knapped flint to form decorative motifs.