A short drive from Norwich took me to visit this whimsical building. The pinnacles of what at first appears to be a Late Gothic church towering over the undulating countryside between Cawston and Reepham. What could justify the imposing size of this church? Not located in a centre of any significance, the church is surrounded only by a few farms, cottages, and a school converted into a house. Did it belong to a former monastery? Was it part of the estate of a country house?

Upon approaching the church, I realise that the building is not mediaeval, but a fine neo-Gothic pastiche. St Michael’s served as a parish church for only eight years after its completion. Too large a building for too small a flock, and the associated maintenance costs, eventually made it redundant. Dubbed the ‘Cathedral of the Fields’, the church is now managed by the Churches Conservation Trust.

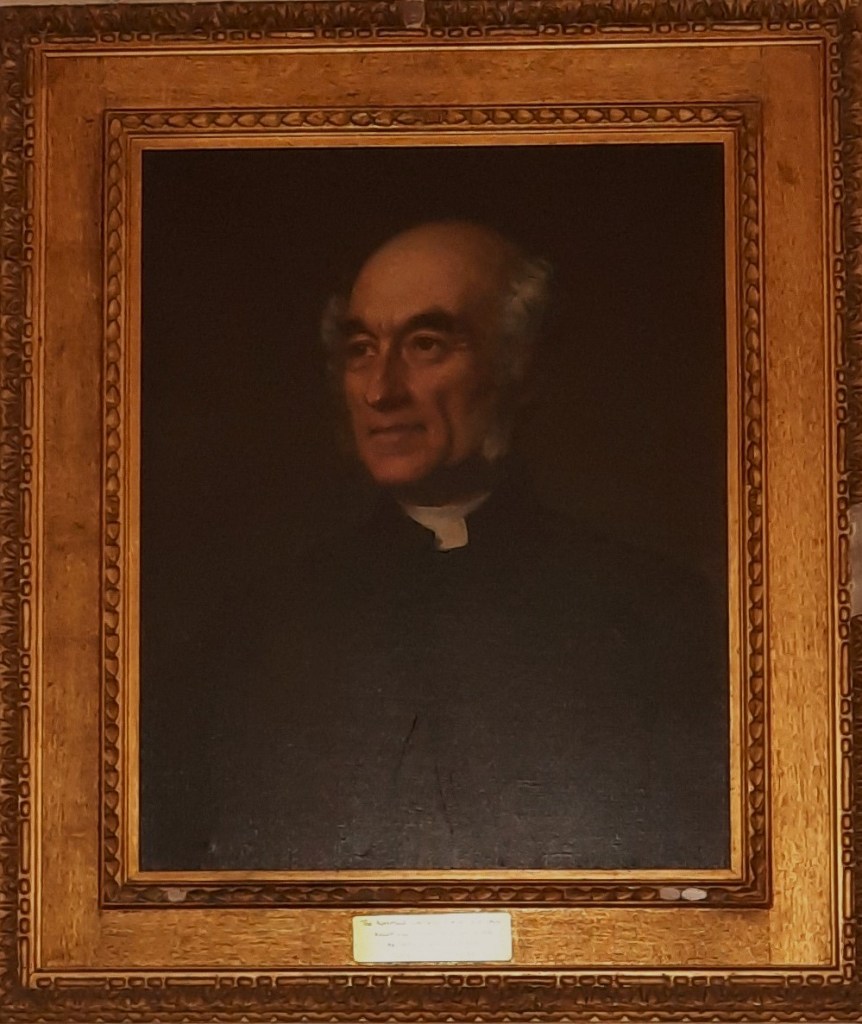

St Michael’s was envisioned by a remarkable man, Reverend Whitwell Elwin (1816-1900), who single-handedly designed the church and funded its erection on the property acquired in 1713 by his relation – the great-grand son of Pocahontas. Whitwell came from a long line of Norfolk landed gentry and studied law at Cambridge. Instead of a career as a lawyer like several family members before him, Whitwell chose to become a man of the cloth and was ordained in 1840. Nine years later, Edwin took over his cousin Caleb’s curacy in Booton. Whitwell, however, could not be just a parson from a remote corner of Norfolk for too long. Between 1853 and 1860, he was an editor for the Quarterly Review and published important essays including Alexander Pope’s works and the Origin of species by Charles Darwin in 1859. Though initially sceptical of evolutionism, Whitwell was convinced by the evidence accurately put forward by Darwin, and the two became good friends. Among other notable acquaintances of the Norfolk parson were the likes of John Forster (Dickens’ biographer), novelist William Thackeray, Lord Lytton, and architect Edwin Luytens.

“Elwin is credited with having brought the Review’s attitude up to date, improved the quality of its writing and both the range and distinction of its contributors. It was the volume of editorial correspondence that forced the Post Office to install the letter box at Booton.”1

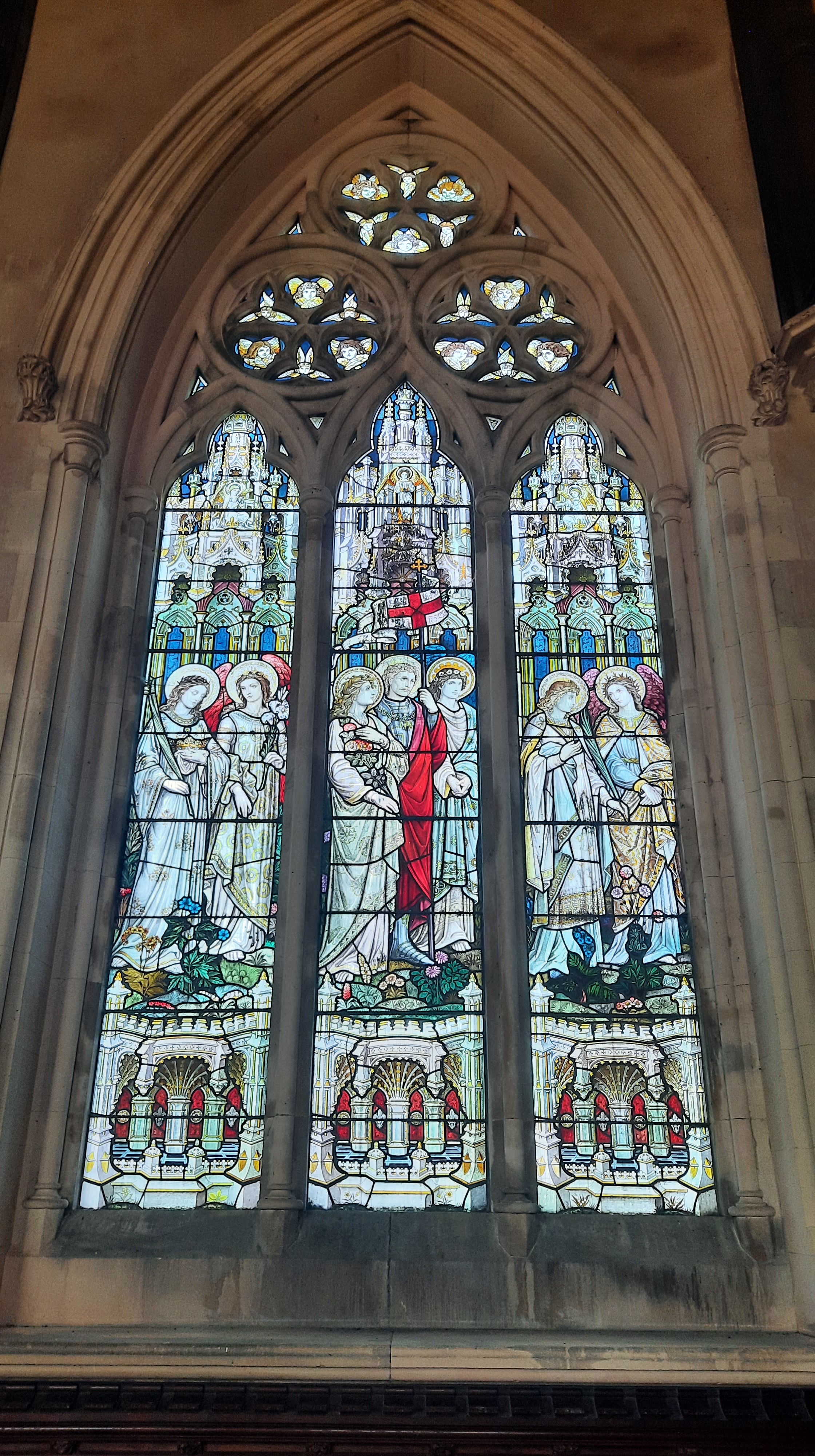

Architect Thomas Allom (1804-1872) was commissioned the remodelling of the former Rectory completed in an Elizabethan style. Despite the lack of any architectural training, Whitwell tackled the pre-existing mediaeval church, which was encased in a new building with the addition of a large baptistry, a vestry, and a porch. Nearby St Botolph’s in Trunch and St Mary’s in Burgh-next-Aylsham provided models for the roof and the north doorway. But Whitwell also looked farther afield for inspiration, particularly the architectures he had admired in Somerset and Warwickshire. The west doorway was inspired by Glastonbury Abbey, the triangular opening above the chancel was taken from Lichfield Cathedral, and the stained-glass windows echoed similar examples in Temple Balsall (Warwickshire) and the Palace of Westminster.

The knapped flint used for the exterior was sympathetic to the ubiquitous building material popular in Norfolk, while the limestone was an import from Bath (a fact that was not appreciated by his friend Edwin Luytens). The excessive elevation and abundance of pinnacles, towers, and minarets did not respond to a philological approach to Gothic Revival but were rather the product of Elwin’s mediaevalist and orientalist imagination.

The immense hammerbeam roof over the nave is perhaps the most striking element. The angels were carved by James Minns (1824-1904), a well-known master whose carving of a bull’s head was used as the emblem for Colman’s mustard. Elwin could also count on the help of a professional draughtsman, Mr Horwood of Norwich. The stone carvings were also the work of a local artist, Robert Flood.

Completed between 1880 and 1900, the stained-glass windows in the chancel and baptistry were designed by Cox, Sons & Buckley and the later ones in the nave by Alex Booker. Elwin closely supervised the style and subject of the decorated windows, rejecting any reference to the much-disliked Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Theories of angels and the Church Triumphant were deemed suitable for a church dedicated to St Michael, along with scenes from the Old and New Testaments. In the nave, religious iconography gave way to personal fancy with mass of figures whose angelic, feminine faces depicted Elwin’s ‘Blessed Girls’, a moniker the clergyman used for his female friends.

The architect Edwin Luytens (1869-1944) was a close friend of Whitwell’s. His wife, Lady Emily, entertained a long correspondence with Elwin and mentioned the parson at length in her memoir A Blessed Girl:

Elwin, who was born in 1816, was fifty-eight years my senior. Nevertheless, from the age of thirteen to twenty-three I gave him, in almost daily letters, the entire confidence of a somewhat passionate nature. From him I received a warmth of friendship, coupled with an understanding and sympathy for my youthful problems and heart-aches, rare in the relationship of youth and age. […] Perhaps I should also here explain the title I have chosen for this book. It is in no way intended to place a halo round my own head, but the epithet of ‘blessed’ was used by Elwin to express his feelings towards those whom he especially loved and cherished.2

Emily’s fondness was most evident in her characterisation of the reverend:

Elwin is the last, or one of the last, true men of letters left to us. Scholarship, style, tenderness, discrimination, a vast knowledge of books, and unlimited leisure—he has them all. A more sympathetic companion does not exist among men. He has a wonderful flow and charm of conversation, which wells and bubbles up with great spontaneity from a richly stored mind—a mind in which a wide field of literary culture has blossomed into those flowers of thought and expression which enliven and beautify human intercourse. And the foundation of his character, which gives colour and atmosphere to his mind, is a genuine goodness and rare benignity. His is, I think, one of those natures which are lovable because in them is a great capacity of loving. But to me one of his chief charms is a quick sense of humour, which I think a very rare gift even amongst intellectual people; the majority of mankind seem to be utterly destitute of it.3

About the church designed by Whitwell, Lady Emily reported that her husband did not appreciate its eccentricity and disregard for architectural principles, saying that it was “very naughty, but in the right spirit”.

In the entry dedicated to this church in The Buildings of England, Nikolaus Pevsner, too, could not hide his disapproval of Elwin’s unique brand of Gothic revival: “While the equipment of the chancel is very rich, and perhaps antiquated for the time when Morris and his disciples were busy elsewhere, the fact remains that the architecture and fittings are a result of one man’s personal, and idiosyncratic, vision.”

- A. Barnes, Church of St Michael the Archangel (London: The Churches Conservation Trust, 2007), p. 4. ↩︎

- E. Luytens, A Blessed Girl: Memoirs of a Victorian Girlhood (London: W. Heinemann, 1989), pp. xi-xii. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 14. ↩︎