The ‘Burnhams’ are a group of villages on the North Norfolk coast along the river Burn. Situated on a navigable waterway, these settlements rose to prosperity thanks to trade between the 13th and 15th centuries. Their commercial importance slowly declined with the silting of the river and the emerging of other port town like King’s Lynn, Wells, Blakeney, and Cley in the following century. The largest village, Burnham Market, originated from the merging of Burnham Sutton, Burnham Westgate, and Burnham Ulph. The other Burnhams include: Burnham Overy Staithe, Burnham Overy Town, Burnham Deepdale, Burnham Norton, and Burnham Thorpe. Only a few miles along the coast, is the village of Brancaster, whose name indicates its military origin as part of a system of forts the Romans built to defend the Norfolk coast from barbarian attacks.

Norfolk has been called Nelson’s County because the celebrated Admiral of the British Navy, Horatio Nelson, was born in Burnham Thorpe on 29 September 1758. His father, Edmund Nelson, was the rector of the village parish, and his mother, Catherine Suckling, was related to Sir Robert Walpole. Between 1768 and 1771, Nelson completed his education at Paston Grammar School in North Walsham and King Edward VI’s Grammar School in Norwich. Following in the footsteps of his uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling, he soon began what would be a stellar career in the navy, leaving the native village in 1771. Years later, in 1788, Nelson returned to his birthplace and settled in Burnham Thorpe with his wife, Frances Nisbet, until he was called back to service in 1793.

LEFT: Sir William Beechey, Horatio Nelson, 1800, London, National Portrait Gallery; Image: © National Portrait Gallery, London; RIGHT: The Parsonage House of Burnham Thorpe, pl. from J. Stanier Clarke and J. McArthur, The Life and Services of Horatio Viscount Nelson (London 1809), vol. I.

Burnham Deepdale

The first thing one notices of St Mary’s church is the fine Anglo-Saxon round tower. Inside it, hangs a rare 15th-century bell cast by Thomas Derby of King’s Lynn. The North doorway is from ca. 1190 and the North arcade from the 14th century. The exterior, however, was restored in 1875-76 by the High Gothicist architect and glass designer Frederick Preedy (1820-1898).

The baptismal font dates to the early 12th century and is made from Barnack stone from Rutland. After suffering damage in the 18th century, it was subsequently repaired and repositioned on a new base in the 19th century. The carvings depict the Labours of the Months, that is, the cycle of agricultural activities taking place in each month. January is represented by a man drinking from a horn, February by a man warming his feet by the fire, March by a man digging, April by a man pruning, May by a man beating the bounds (Rogationtide), June by weeding, July by mowing, August by binding a sheaf, September by threshing, October by grinding corn, November by slaughtering a pig, and December by feasting together. The name of the month in Latin is inscribed on some panels. The West side of the font is decorated with four Trees of Life and the top frieze shows carvings of animals and plants. It is exquisitely Norman and the subject befits the rural surroundings. Albeit more modest, these carvings find a parallel in the tympanum of the Benedictine Abbey of Vézelay (Burgundy), where monthly activities were represented in conjunction with the zodiac signs. Miles apart, admittedly, but Benedetto Antelami’s reliefs for the Baptistry in Parma also come to mind (late 12th century).

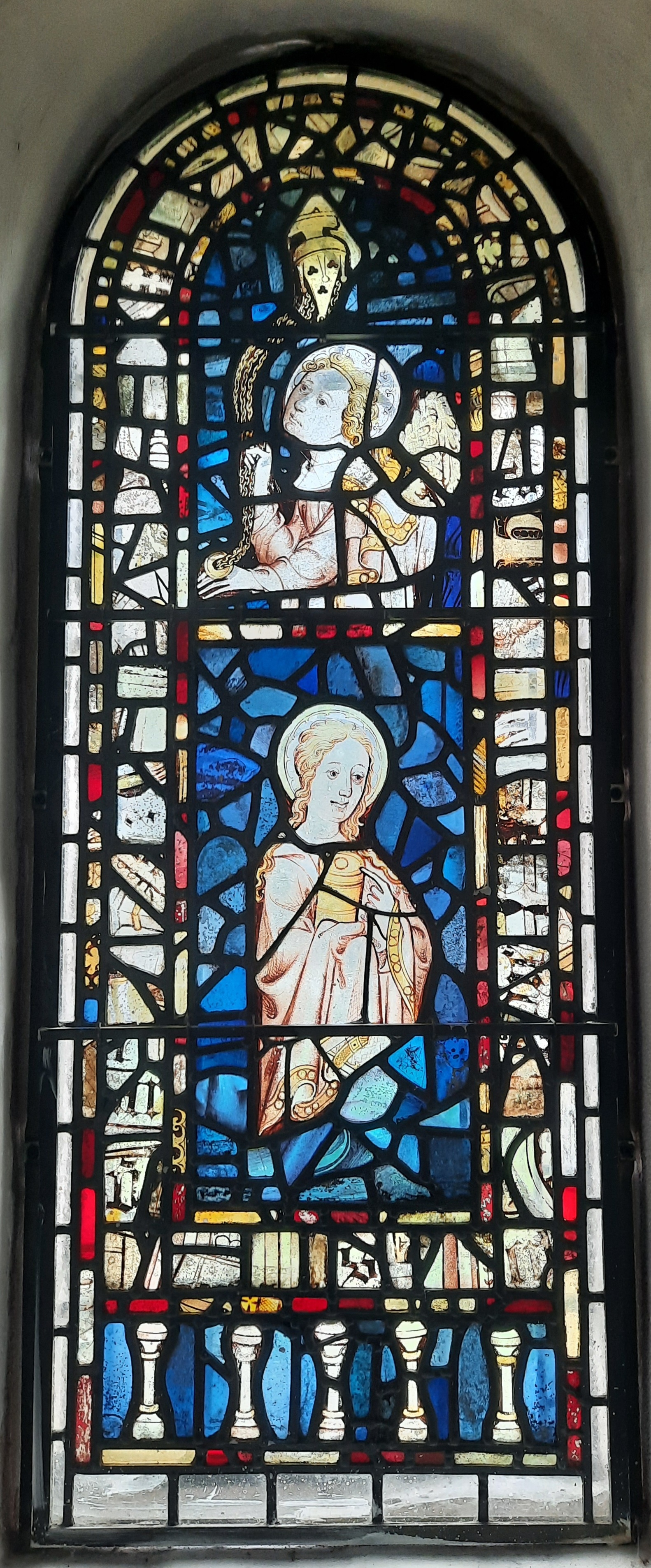

The collection of stained glass windows is most remarkable. As can be expected, Preedy left his mark when he restored the church and designed the windows in the chancel and aisle. But the attention immediately turns to the older windows made of many different fragments. Their very existence is testament to a history that was as fragile as the material they are made of. How very few examples could survive the dissolution of the monasteries can be easily imagined. Another wave of destruction came with Puritan iconoclasm in the 17th century. More often than not, only those that were too high to reach, or rescued and hidden away, are what we can see today. East Anglia was notably vandalised by the Parliamentary Visitor William Dowsing (1596-1668), which earned him the nickname ‘Smasher Dowsing‘. His steadfast commitment to removing or defacing monuments of idolatry and superstition was carefully documented in a detailed journal.

Early evidence shows that patrons mostly relied on overseas masters until the 13th century when native schools began to emerge. Norwich was among them, though little remains from that time. By the 15th century, Norwich boasted a thriving school of glass painters whose signature motifs included a holly leaf curled around a pole (see St Peter Mancroft in Norwich).

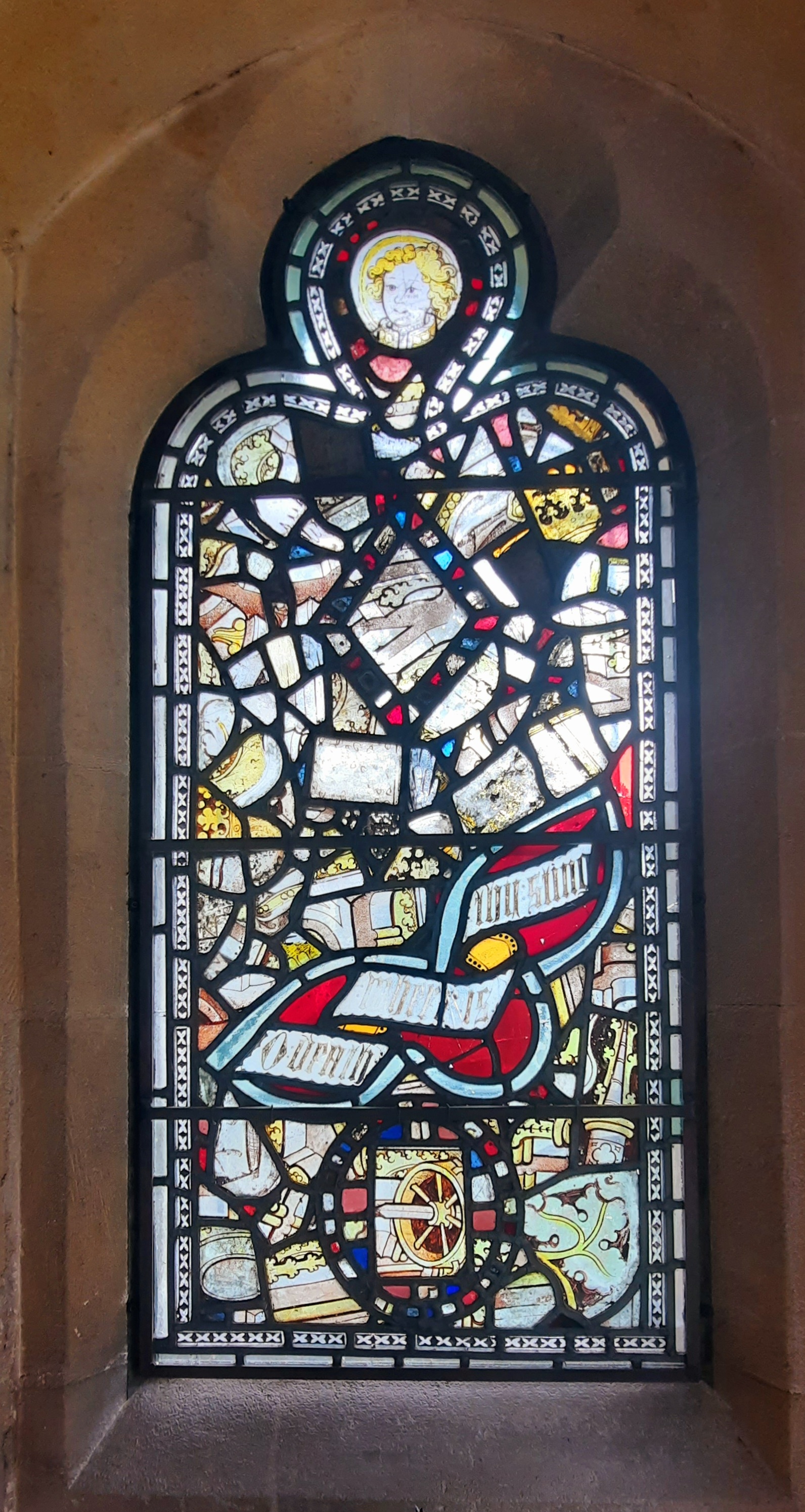

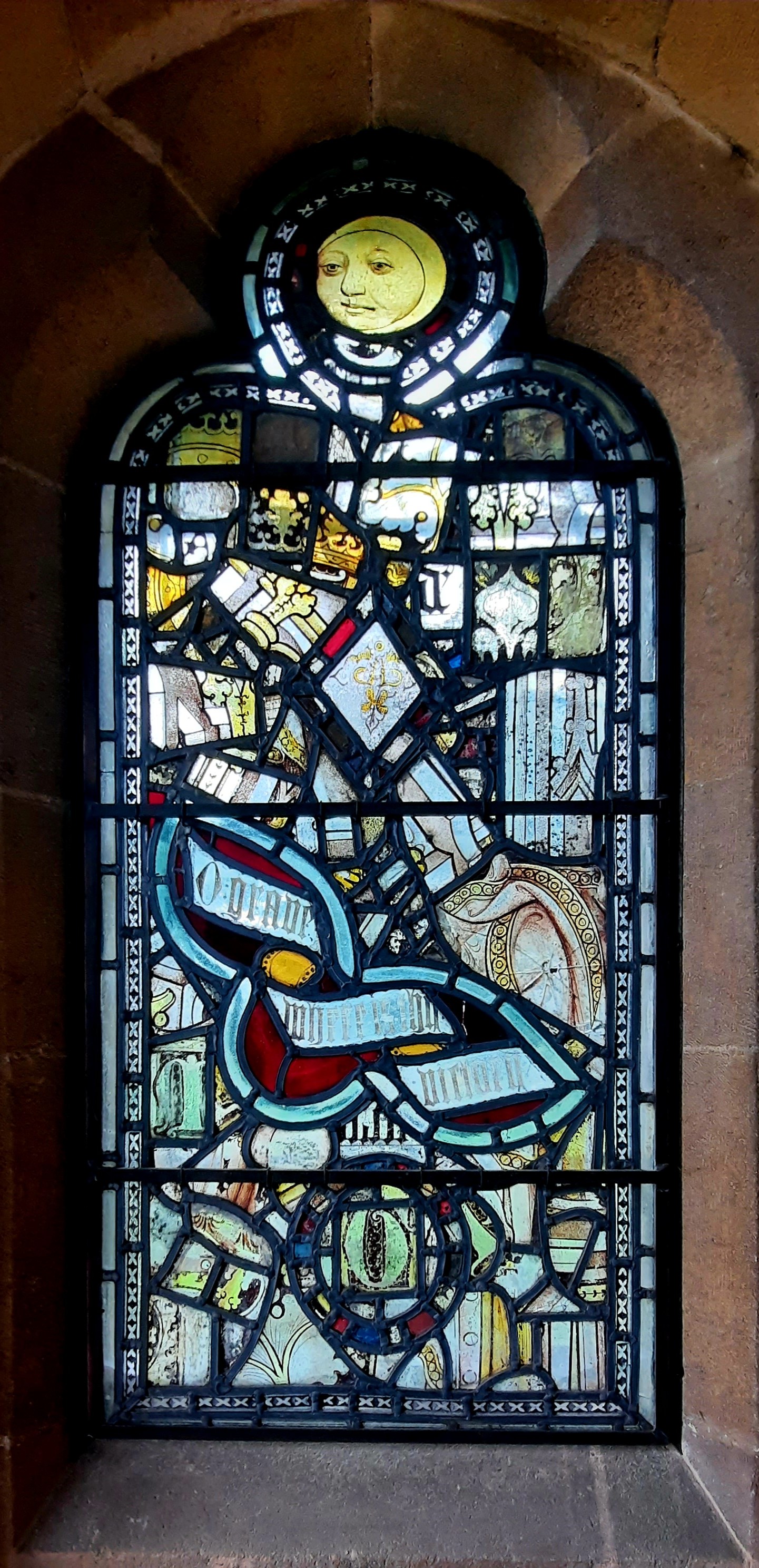

When stained glass windows were restored in Victorian times, mediaeval fragments were often used in conjunction with modern glass to create painted jigsaws. Likewise, the windows in Burnham Deepdale were created by combining fragments from the 14th and 15th centuries. The two windows in the porch are known as the Sun and the Moon because of the heads at the top of the window – possibly coming from a Crucifixion originally. The fragments include the inscription ‘Death where is thy sting’.

The West window in the tower features an almost complete figure of Mary Magdalene in a pink robe holding an ointment pot; above her, an angel is pulling triple chains attached to a censer. Both vestry windows have fragments with canopies, architectural designs, and 14th-century heraldic borders. But the most striking piece is the window in the North aisle with a mid-15th century roundel of the Trinity, musical angels, and a nimbed queen with arrows identified with St Ursula. The rose-en-soleil, that is, the white rose on a yellow rayed sun, belongs to Edward IV and is a common pattern in painted windows. The word ‘Gelda’ suggests the patronage of a guild while the merchant’s mark on the top refers to another patron. The practice of immortalising donors began in the 13th century, though inscriptions and heraldry were still the main identifiers. It will not be until the 15th century that glass painters would achieve true likeness in their portraits.

Burnham Norton

This beautiful mediaeval church sits on top of a hill with a stunning view over the fields stretching out to the sea. Like its neighbour in Burnham Deepdale, this religious building has an Anglo-Saxon round tower with bricked windows. The rest of the church was rebuilt from the 13th century onwards. The clerestory with four two-light windows was a 15th-century addition. The windows are Late Perpendicular Gothic. Even on a cloudy day, the interior is filled with light and the simplicity of the naves with circular and octagonal piers is worthy of a Cistercian abbey. After all, a man with iconoclastic tendencies such as St Benedict would have also approved of the whitewashed walls!

Perhaps not as remarkable as the one in Burnham Deepdale, the Norman font consists of a large, square bowl on five stocky columns with cushion capitals. Walking towards the altar, traces of mediaeval wall painting around the chancel arch and what remains of a Crucifixion on the north arcade come into view.

Dating to 1450 is the marvellous hexagonal painted pulpit with the four Latin Church Fathers (St Augustine, St Jerome, St Gregory the Great, St Ambrose) and the donors, Johannes Goldalle and his wife Katherina. The Fathers are seated on highly decorated thrones and are depicted at their desks, reading, writing, or sharpening a pen. In keeping with the traditional iconography, the activities of the four Doctors of the Church recall their role in formulating Christian doctrine. In 1973, conservation work by Pauline Plummer removed the heavy overpainting. The other pulpit was made in the 19th century with Jacobean panels. The nave is separated from the chancel by a rood screen which an inscription dates to 1458 and refers to William Groom. The panels were once decorated by paintings that suffered post-Reformation defacing. The ornate partition was restored in 1953 by Howard Brown who also added a new coving.

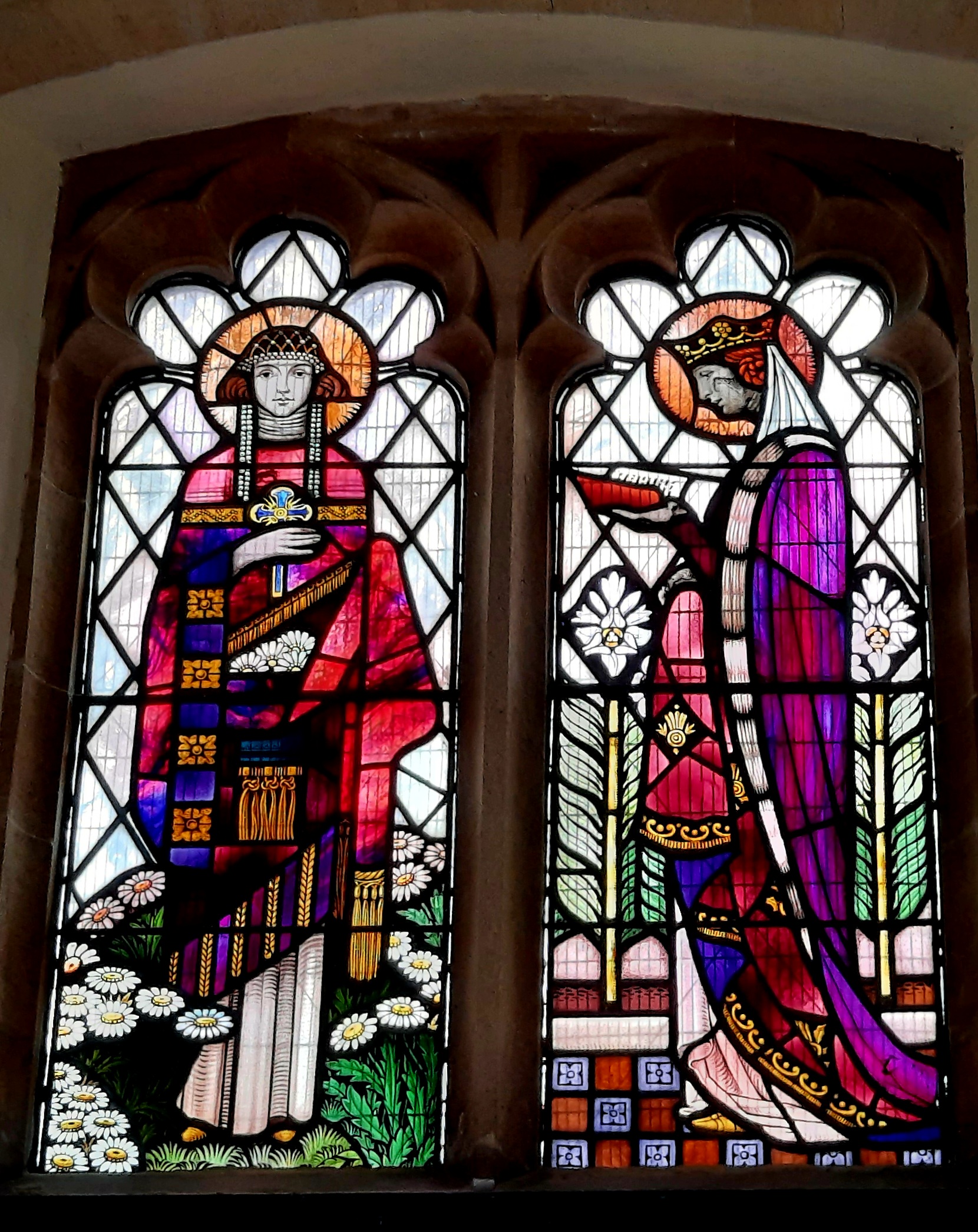

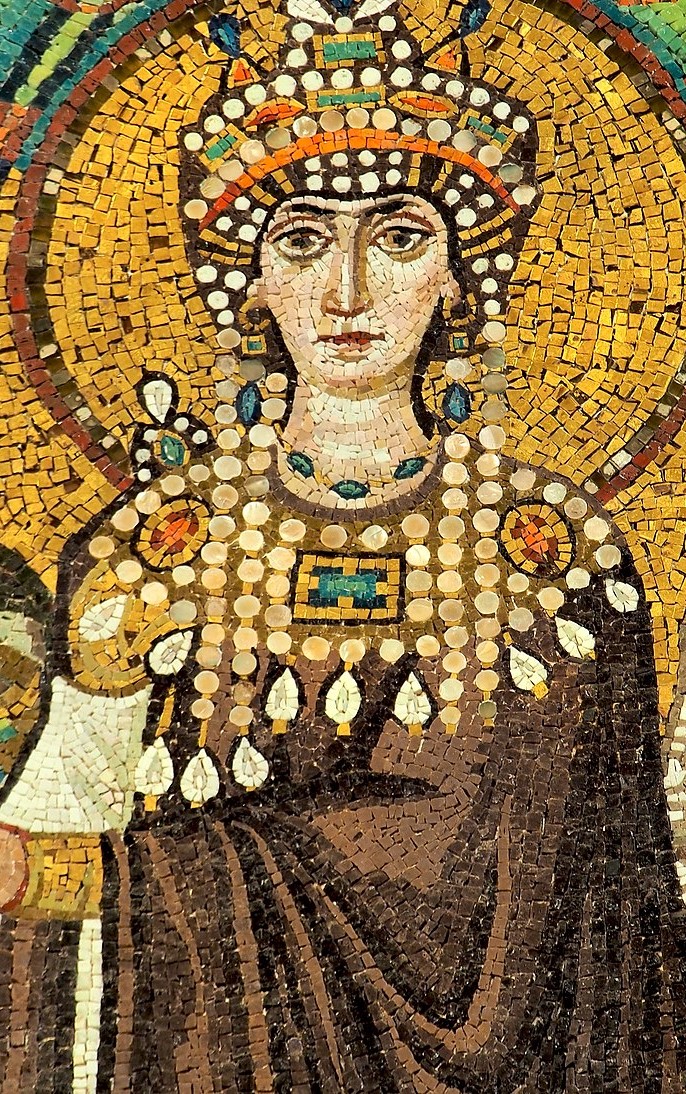

Behind the screen, the choir inner sanctum is dominated by an intriguing stained glass window dated 1927 and attributed to Trena Cox (1895-1980). The St Margaret of Antioch and St Margaret of Scotland represented in the two lights are both archaic and modern. Their hieratic posture and geometric simplification echo Byzantine mosaics as well as the Glasgow School style of Rennie Mackintosh. On the left, St Margaret of Antioch faces the viewer with a cross in her hand, the instrument that saved the martyr from being swallowed by the dragon. The marguerite daisies in her other hand and in the flower-filled meadow at her feet are an obvious allusion to her name. Her hairstyle and the mesh headpiece, together with the straight, elongated line of her robe may be a subtle nod to 1920s fashion. Margaret’s hieratic pose and headpiece (including the pearls hanging down each side) also suggests that the artist looked to the Byzantine mosaic in Ravenna of Queen Theodora for inspiration. Less femme fatale of the roaring twenties, more Syrian virgin martyr of the 4th century. St Margaret of Scotland is shown in profile, intent on reading a book, an attribute that recalls the pious influence on her husband to whom she read passages from the Bible. Margaret is wearing a crown as she was an English princess who became Queen of Scotland after marrying Malcolm III. If the flowers behind her are indeed white amaryllises, then they could be a reference to the old Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Wessex that is also associated with her name.